Here’s a feat of visual athletics to amaze your friends with this week. During your daily routine, you may have noticed the daytime Moon hanging against the azure blue sky. But did you know that, with careful practice and a little planning, you can see Venus in the broad daylight as well?

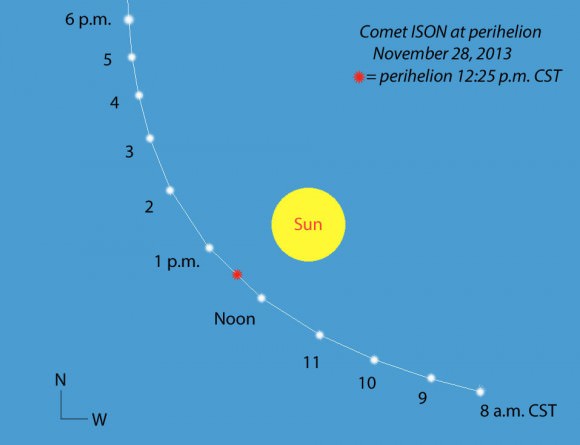

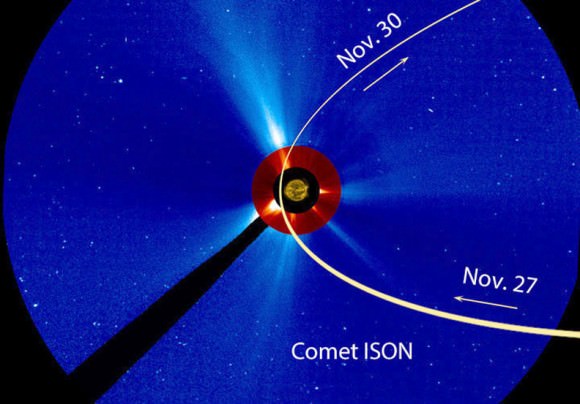

This week offers a great chance to try, using the daytime Moon as a guide. We recently wrote about the unique circumstances of this season’s evening apparition of the planet Venus. On Friday, December 6th, Venus will reach a maximum brilliancy of magnitude -4.7, over 16 times brighter than Sirius, the brightest star in the sky. And just one evening prior on Thursday December 5th, the 3-day old crescent Moon passes eight degrees above it, slightly closer together than the span of your palm held at arm’s length.

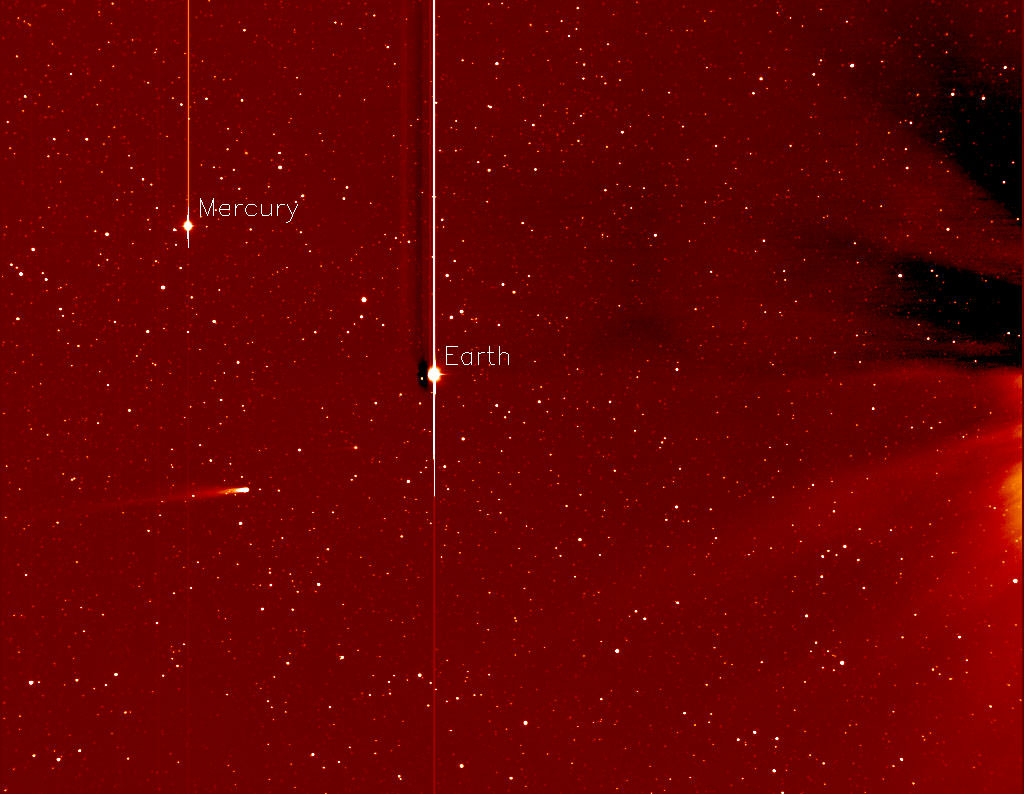

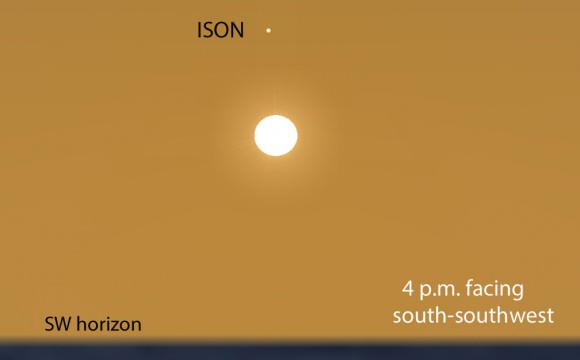

The Moon will thus make an excellent guide to spot Venus in the broad daylight. It’s even possible to nab the pair with a camera, if you can gauge the sky conditions and tweak the manual settings of your DSLR just right.

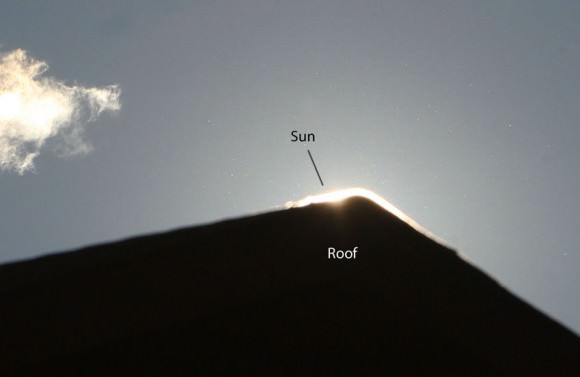

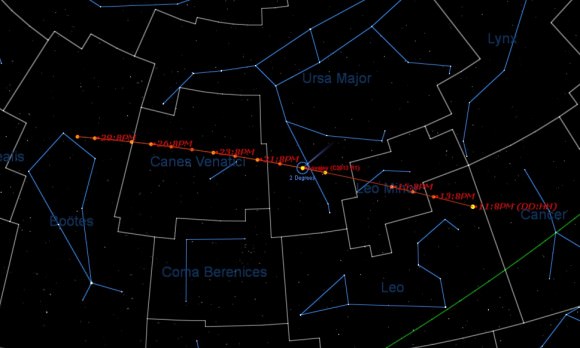

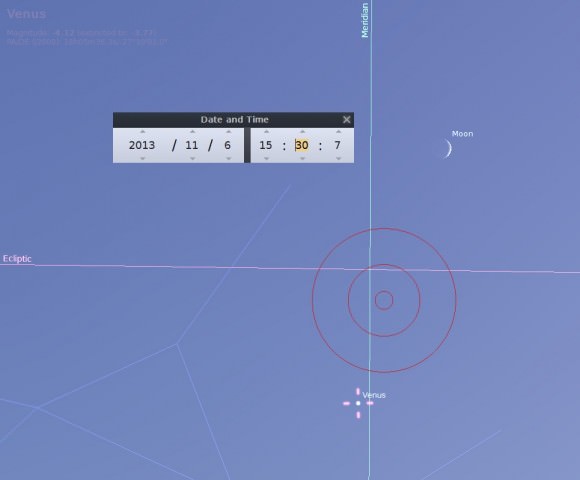

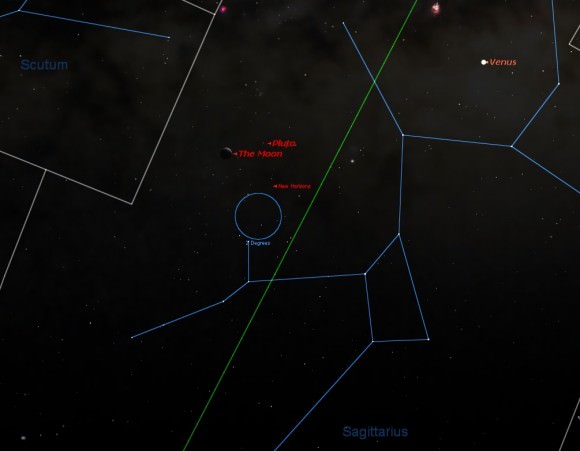

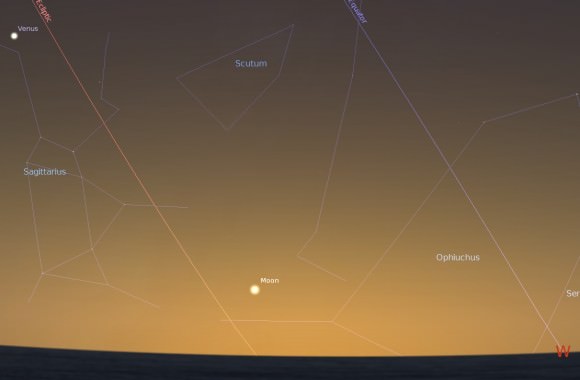

The best time to attempt this feat on Thursday will be when the pair transits the local meridian due south of your location. Deep in the southern hemisphere, the Moon and Venus will appear to transit to the north. This occurs right around 3:00 PM local. The fingernail Moon will be easy to spot, then simply begin scanning the sky to the south of it with the naked eye or binoculars for the brilliant diamond of Venus. High contrast and blocking the Sun out of view is key — Venus will easily pop right out against a clear deep blue sky, but it may disappear all together against a washed out white background.

The Moon will be at a 10% illuminated phase on Thursday, while Venus presents a slimming crescent at 27% illumination. Though tougher to find, Venus is actually brighter than the Moon in terms of albedo… expand it up to the apparent size of a Full Moon and it would be over four times as bright!

You’ll be amazed what an easy catch Venus is in the daytime once you’ve spotted it — we’ve included views of Venus in the daytime when visible during sidewalk star parties for years.

Due to its brilliancy, Venus has also been implicated in more UFO sightings than any other planet, and even caused the Indian Army to mistake the pair for snooping Chinese drones earlier this year when it was in conjunction with the planet Jupiter. A daytime sighting of the planet Venus near the Moon was almost certainly the “curious star” reported by startled villagers observing from Saint-Denis, France on January 13th, 1589.

Venus can also cast a noticeable shadow near greatest brilliancy, an effect that can be discerned against a fresh snow-covered landscape. Can’t see it? Take a time exposure shot of the ground and you may just be able to tease it out… but hurry, as the waxing Moon will soon be dominating the early evening night sky show!

Another phenomenon to watch for this week on the face of the waxing crescent Moon is known as Earthshine. Can you just make out the dark limb of the Moon? This is caused by the Earth acting as a “mirror” reflecting sunlight back at the nighttime side of the Moon. And don’t forget, China’s Chang’e-3 lander plus rover will be landing on the lunar surface in the Sinus Iridum region later this month on December 14th, the first lunar soft landing since 1976!

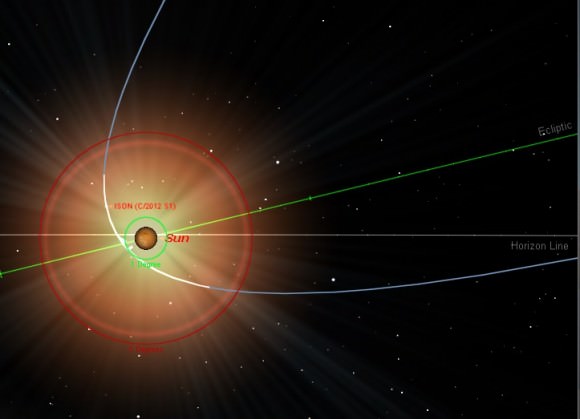

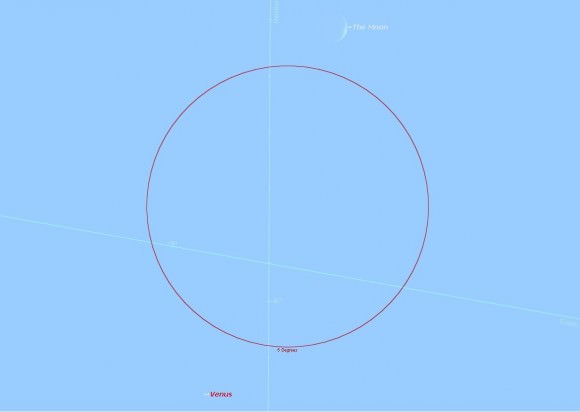

The imaginary line of the ecliptic currently bisects the Moon and Venus, as Venus sits at an extreme southern point 2.5 degrees below the ecliptic — in fact, 2013 the farthest south it’s been since 1930 — and the Moon sits over four degrees above the ecliptic this week. The Moon also reached another notable point today, as it reached its most northern “southerly point” for 2013 at a declination of -19.6 degrees. The Moon’s apparent path is headed for a “shallow year” in 2015, after which it’ll begin to slowly widen over its 18.6 year cycle out to a maximum declination range in 2024. It’s a weird but true fact that the motion of the Moon is not fixed to the Earth’s equatorial plane, but to the path of our orbit traced out by the ecliptic, to which its orbit is tilted an average of five degrees.

And speaking of the Moon, there’s another fun naked-eye feat you can attempt tonight. At dusk, U.S. East Coast observers might just be able to pick up the razor thin crescent Moon hanging low to the West, only 23 hours past New. Begin scanning the western horizon about 10 minutes after sunset. Can you see it with binoculars? The naked eye? Chances get better for sighting the slim crescent Moon the farther west you go. North American observers will have a chance at a “personal best” during next lunation in the first few days of 2014… more to come!

Be sure to send those Venus-Moon conjunction pics in to Universe Today!