It’s always interesting to consider the astronomical goings-on that occur under alien skies.

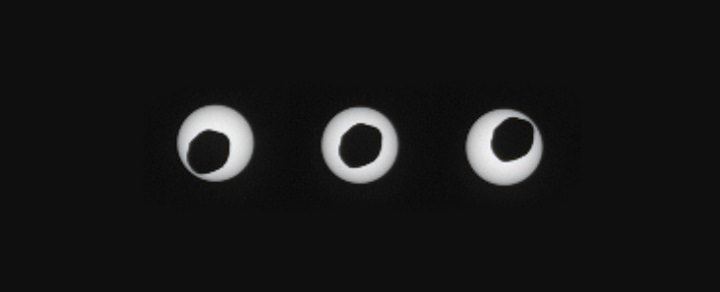

On August 17th, Curiosity wowed us once again, catching the above sequence of images of the Martian moon Phobos transiting the Sun.

Such phenomena have been captured by the Curiosity, Opportunity and Spirit rovers before, as the twin Martian moons of Deimos & Phobos cross the face of the Sun. But these recent images taken by Curiosity’s right Mastcam pair are some of the sharpest yet.

Orbiting only an average of 6,000 kilometres above the surface of Mars, Phobos is the closest to its primary of any moon in the solar system. It appears about 11 arc minutes in size when directly overhead, about 3 times smaller than our own Moon does from the Earth.

“This event occurred near noon at Curiosity’s location, which put Phobos at its closest point to the rover, appearing larger against the Sun than it would at other times of the day,” Said co-investigator Mark Lemmon of Texas A&M University in a recent press release. “This is the closest to a total eclipse that you can have on Mars.”

Phobos is 40% more distant from an observer standing on the surface of Mars when it is rising above the local horizon than when it is overhead. The Sun is about 20’ arc minutes across as seen from Mars, 66% of its diameter as seen from the Earth.

The sequence above spans only six seconds in duration. You would easily note the apparent motion of Phobos as it drifted by! Also, since Phobos orbits Mars once every 7.7 hours, it actually rises in the west and sets in the east. The Martian day is over three times this span, at 24.6 hours long. Deimos has a more sedate orbit of 30.4 hours in duration.

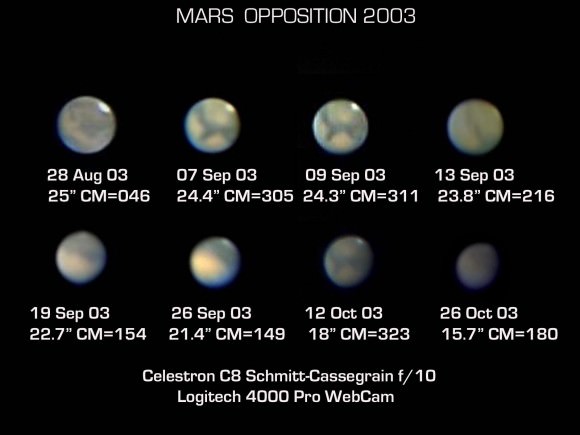

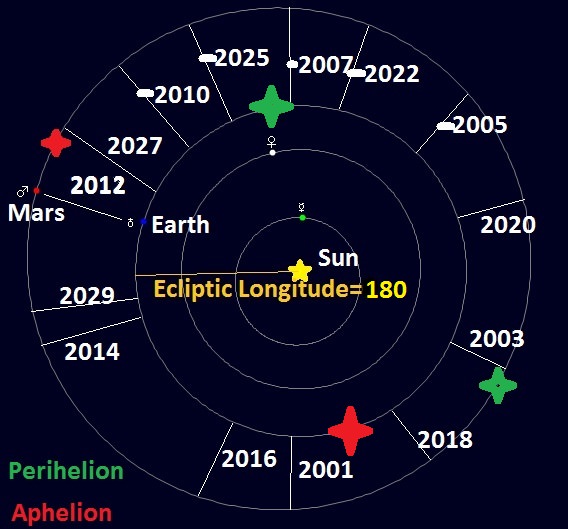

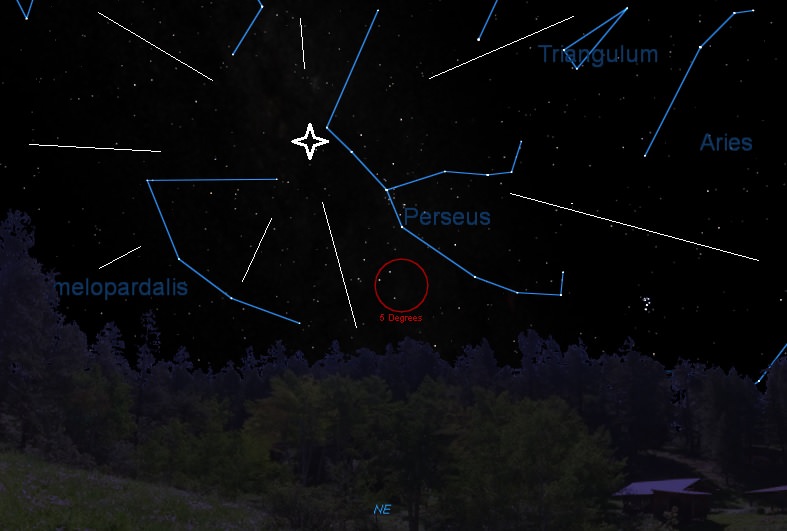

The twin Moons of Deimos and Phobos were discovered this month back during the opposition of 1877 by Asaph Hall using the United States Naval Observatory’s newly installed 65 centimetre refractor. The moons are just within the grasp of eagle-eyed amateurs near opposition. You’ve got another opportunity to cross these elusive moons off of your life list coming up in the Spring of 2014.

It’s especially captivating that you can make out the irregular “potato shape” of Phobos in the above images. With low orbital inclinations relative to the equator of Mars of 1.1 degrees for Phobos and 0.9 degrees for Deimos, solar transits are not an uncommon occurrence, transpiring somewhere along the Martian surface with every orbit. If Phobos were twice as close to Mars, it would completely cover the Sun in a total solar eclipse. What Curiosity gave us this month is more akin to an annular eclipse with a ragged central shadow. An annular eclipse occurs when the occulting body is too distant to cover the Sun, leaving a bright, shining ring, or annulus.

On the Earth, we live in an epoch where annular eclipses are slightly more common than total solar eclipses, as the Moon currently recedes from us to the tune of 3.8 centimetres a year. About 1.4 billion years from now, the last total solar eclipse will be seen from the Earth. The next purely annular eclipse as seen from Earth occurs on April 29th, 2014 across Australia and the Antarctic.

Conversely, Phobos is in a “death spiral,” meaning that it will one day crash into Mars about 30-50 million years from now. This also means that in about half that time, it will also be large enough to visually cover the Sun when crossing it near local noon. For a brief time far in the future, jagged total solar eclipses will be visible from Mars. That is, if the gravitational field of Mars doesn’t rip Phobos apart before that!

But beyond just aesthetics, these observations serve a scientific purpose as well. These phenomena serve to refine our understanding of the precise positions of Phobos and Deimos and their orbits.

“This one is by far the most detailed image of any Martian lunar transit ever taken, and it is especially useful because it is annular. It was taken closer to the Sun’s center than predicted, so we learned something.”

The track during the August 17th observation was off by about 2-3 kilometres, allowing for a surprise central transit of the Sun as seen from Curiosity’s location.

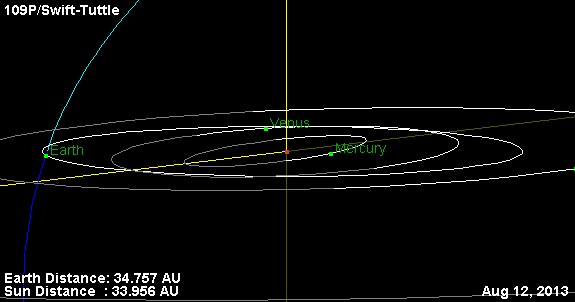

Both Phobos and Deimos are captured asteroids only 22.2 & 12.6 kilometres across, respectively. Both must be subject to occasional bombardment from meteorites blasted off of the surface of nearby Mars. Sample return missions to Phobos have been proposed. Russia’s ill-fated Phobos-Grunt mission would’ve done just that.

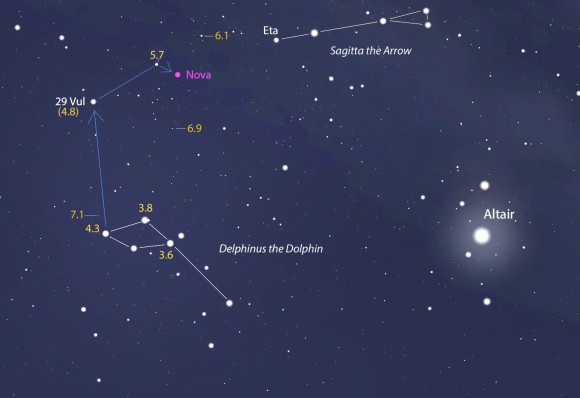

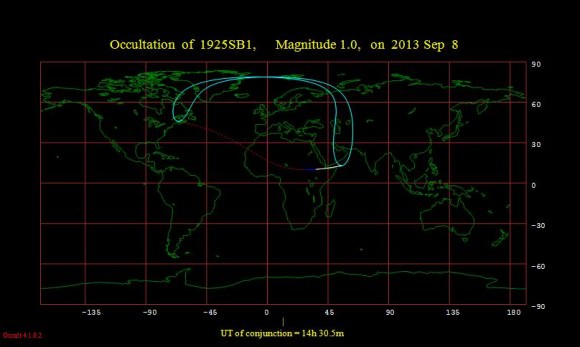

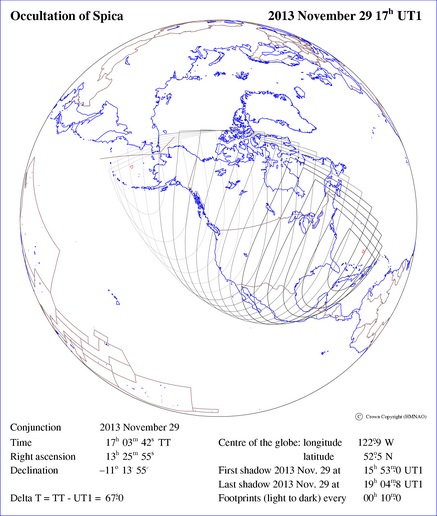

Will humans ever stand on the surface of the Red Planet and witness an annular eclipse of the Sun by Phobos in person? Well, if we make it there by November 10th, 2084, observers placed on the slopes of Elysium Mons will witness just such an event… with a rare transit of Earth and the Moon to boot!:

Arthur C. Clarke wrote of a transit of Earth from Mars that occurred in 1984 in his science fiction short story Transit of Earth.

Hey, I’m marking my calendar for the 2084 event… assuming, of course, my android body is ready by then!