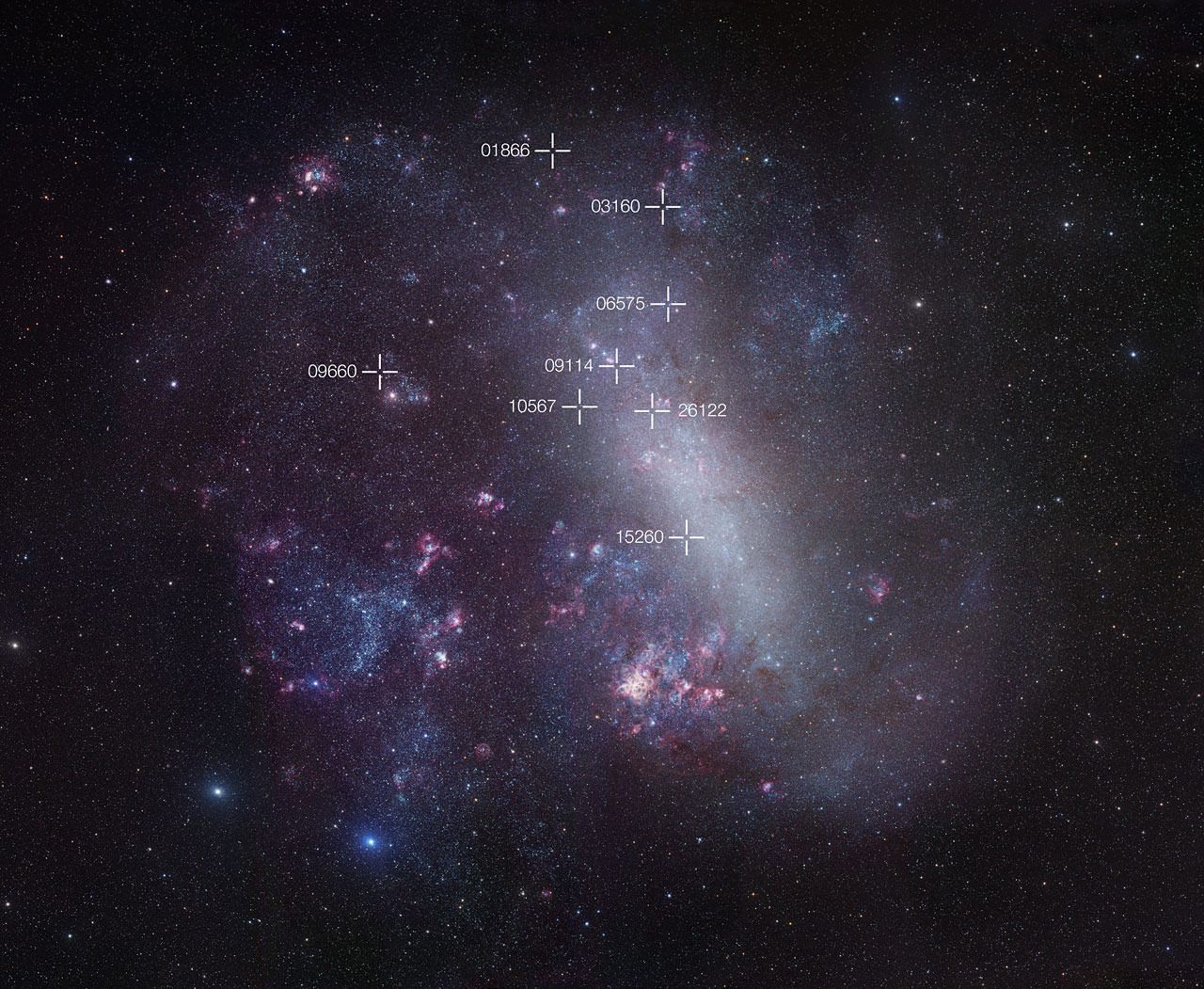

Precise observations of a rare class of binary stars have now allowed a team of astronomers to improve the measurement of the distance to one of our neighboring galaxies, the Large Magellanic Cloud, and in the process, refine the Hubble Constant, an astronomical calculation that helps measure the expansion of the Universe. The astronomers say this is a crucial step towards understanding the nature of the mysterious dark energy that is causing the expansion to accelerate.

The team used telescopes at ESO’s La Silla Observatory in Chile, the Las Campanas Observatory also in Chile and two from the University of Hawaii at Manoa, and the Las Campanas Observatoryas well as others around the globe. These results appear in the 7 March 2013 issue of the journal Nature.

The new distance to the LMC is 163,000 light-years. The LMC is not the closest galaxy to the Milky Way; Canis Major Dwarf Galaxy, discovered in 2003 is considered the actual nearest neighbor at 42,000 light-years from the Galactic Center, and the Sagittarius Dwarf Elliptical Galaxy is about 50,000 light-years from the core of the Milky Way.

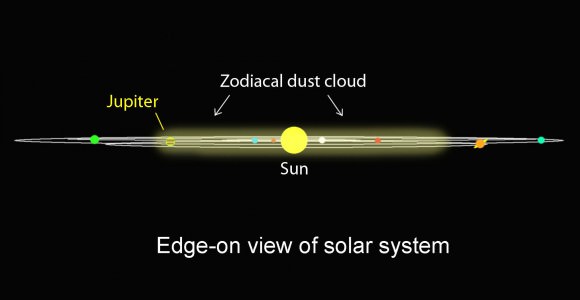

Astronomers ascertain the scale of the universe by first measuring the distances to close-by objects and then using them as standard candles — objects of known brightness — to pin down distances farther and farther out in the universe.

Up to now, finding an accurate distance to the LMC has proved elusive. Stars in that galaxy are used to fix the distance scale for more remote galaxies, so it is crucially important.

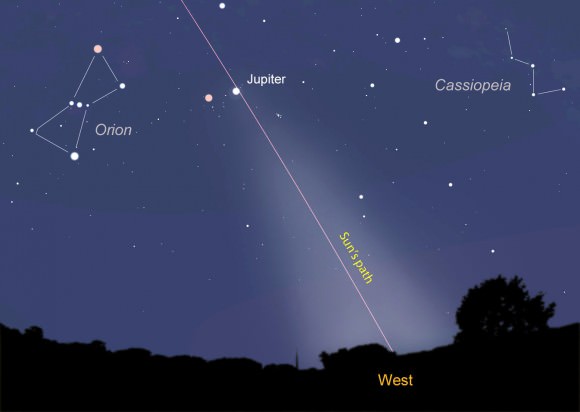

“This is a true milestone in modern astronomy. Because we know the distance to our nearest neighbor galaxy so precisely, we can now determine the rate at which the universe is expanding — the Hubble constant — with much better accuracy. This will allow us to investigate the physical nature of the enigmatic dark energy, the cause of the accelerated expansion of the universe,” says Dr. Rolf-Peter Kudritzki, an astronomer at the University of Hawaii’s Institute for Astronomy.

“For extragalactic astronomers,” said Dr. Fabio Bresolin, also from UH, “the distance to the Large Magellanic Cloud represents a fundamental yardstick with which the whole universe can be measured. Obtaining an accurate value for it has been a major challenge for generations of scientists. Our team has overcome the difficulties using an exquisitely accurate method, and is already working to cut the small remaining uncertainty by half in the next few years.”

The team worked out the distance to the LMC by observing rare close pairs of stars known as eclipsing binaries. As these stars orbit each other, they pass in front of each other. When this happens, as seen from Earth, the total brightness drops, both when one star passes in front of the other and, by a different amount, when it passes behind.

By tracking these changes in brightness very carefully, and also measuring the stars’ orbital speeds, it is possible to work out how big the stars are, what their masses are, and other information about their orbits. When this is combined with careful measurements of the total brightness and colors of the stars, remarkably accurate distances can be found.

“Now we have solved this problem by demonstrably having a result accurate to 2%,” states Wolfgang Gieren (Universidad de Concepción, Chile) and one of the leaders of the team.

Sources: University of Hawaii, ESO