A home-made equatorial wedge used with an off-the-shelf telescope, just one of the ways you can improve your telescope experiences. Credit: Dale Jacobs

Editor’s note: Interested in DIY telescopes? Amateur astronomer Dale Jacobs will be sharing his experiences in using everyday items to build or enhance telescopes.

I am an amateur astronomer and have been since the late 1970’s. I’ll be sharing some of my adventures in building and modifying telescopes for my personal use. Hopefully I can help instill the ‘bug’ in those of you who have been thinking of building your own scope but have yet to do it, or help others avoid some of my pitfalls. I’ll also be sharing my successes, which has inspired me to continue and enhance my stargazing endeavors. As you’ll see, it doesn’t always require expensive equipment, and I’ll show you how to be creative in using some things that you may have right in your kitchen cupboard or garage.

But first: how did I get started in this great hobby? Back in the 70’s I lived in a beachside studio apartment in overly crowded southern California. One chilly mid-November night (on my birthday!) I decided to go for a walk on the mostly deserted beach in front of my apartment complex to meditate and take in whatever stars I could see through the bright city lights. When I got down to the water and looked up, I was surprised to see a swarm of meteors overhead! Wow! Unknown to me at the time, this was the annual Leonid Meteor shower. I felt blessed and lucky to see those Leonids, which fell in near ‘storm’ proportions that year. I was truly amazed and watched for hours. Soon after, I began reading Sky and Telescope and Astronomy magazines to find out more about what I’d seen and then I signed up for an astronomy class at the local junior college.

One of my upstairs neighbors in the apartment building I lived in, heard about my new fascination and offered to lend me an unused and quite dusty 80mm ‘dime store’ refractor. The telescope was mounted on a poorly built alt-azimuth style tripod and came with three overpowered and very small eyepieces. Only one of them was any good and even so the eye relief was just terrible. No matter, I was young and had good eyes back then. So I took that telescope out every chance I could get and was amazed to see Jupiter’s bands and its brighter moons, Saturn’s rings with Titan, and the great Orion Nebula! The Moon soon became a constant companion as my fascination grew.

In 1984 after breaking up with my fiancée, I decided I needed a change of pace to keep from going crazy. So I quit my aerospace job and moved to Northern California. My new ‘digs’ were on a 1,000 acre cattle ranch half way up Sonoma Mountain. The ranch was only a few miles from the town of Petaluma, yet still had that ‘country’ feel – for a ‘city boy.’ The skies were usually pretty good there, especially when the fog rolled in and covered the lights of the S.F. Bay Area. At times, the brilliant stars above literally ‘took my breath away.’ We didn’t have skies like that down in Southern California! At least not within 100 miles of the greater metropolitan area…

I opted to buy a Meade model 2040, 4-inch Schmidt Cassegrain, fork mounted telescope for about $800 rather than the T.V. I was tempted to buy. This telescope turned out to be a MUCH better ‘deal’ and has been a great night time companion over the years! Since I wasn’t dating or even interested in the opposite sex for a quite awhile, it suited and served me well. A small scope is easy to set up and transport, which is key for casual observing. I even put it on the back of my motorcycle one time and drove up to Lake Tahoe with it! (Minus the tripod – it has screw-in legs for setting up on any suitable flat surface – such as a picnic table.)

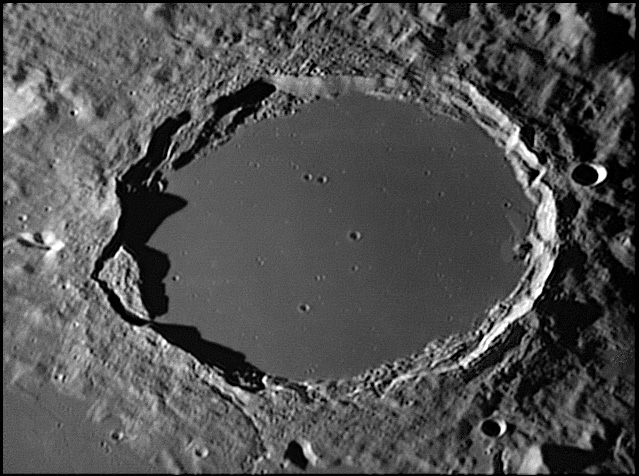

The top image is of that telescope mounted on an equatorial wedge I made for my latitude. The wedge is constructed of a hard wood core, marine grade plywood. It is very stable! The cost for this endeavor was about $10, which included the wood, glue and fasteners. It was well worth the price, and I’m still using it! The tripod is an old surveyor’s backsight that my brother, a land surveyor, found one day working way back ‘in the woods’, up on a mountaintop. It had obviously been forgotten and had been there for who knows how many years. It was probably made in the 1940’s. It sure soaked up/took a lot rejuvenating oil and rubbing to make it useful again, but I like reusing old tools.

Building this equatorial wedge was a great confidence builder and inspired me to continue my star gazing. A 4-inch scope may be considered ‘small’, but a scope this size is a GREAT beginner’s scope and is a handy adjunct for any serious star gazer. Not shown in this image is the tar paper/roofing felt tube I rubber band around the end of the scope for dew protection. Yeah… this is ‘my baby’. It has served me quite well throughout the years! I saw Comet Austin, Comet Halley, Comet Hyakutaki, and Comet Hale Bopp with this scope, along with 41 other comets! I may have been taunted by other astronomers at star parties for having such a ‘small’ scope… but I’ll tell you what… smaller scopes can sometimes ‘see’ through upper atmospheric disturbance cells and are actually better than larger scopes at doing so. I have seen where they will sometimes outperform 8-, 10- or 12-inch scopes! Many times at ‘star parties’ I was the one to found that obscure comet… long before the larger scopes did.

One thing I discovered is that while adequate for casual viewing, this scope doesn’t do all that well with faint galaxies. As a result, I’ve always dreamed of having a larger ‘light bucket’ for those clear nights, when the seeing excels. Then one day, a scientist friend of mine, who was leaving the area to work at the new Virgin Galactic space port in New Mexico, offered to sell me a 12 1/2 inch mirror he’d ground and polished back in the 1970’s. He’d never completed the project due in no small part to the arrival of babies and pressing career responsibilities. Along with the 12 1/2″ mirror he also sold me several components he’d collected to build his ‘dream’ scope, but never did. What you see below is what I ended up doing with some of those components and my own additions.

Here ‘she’ is, warts and all…. my new baby!

Dale’s 12 1/2 inch lightbucket…. or light pot. Image: Dale Jacobs.

The base of the mount I made from a modified aluminum router table. Attached to that is a Doug Fir 2X4 leveling and support base. The leveling screws I made from 8-inch long lag bolts with their rounded heads pointing downwards. The handles of the leveling screws I made from drilled out garden faucet handles. They are captured by stainless steel cap nuts and threaded inserts. The wheels on this side of the base I purchased at a local hardware store, the axle too. The two front wheels on the side opposite, are from a baby carriage! The equatorial wedge I cut from a piece of 1 inch thick plywood. The cast aluminum equatorial mount was made from an old Navy gun alignment bore sight. The R.A. axis is mounted where the spotting or alignment scope once lived. The clamps that held that bore scope now hold the R.A. shaft bearings in place.

Here’s what I did with the old refractor/bore sight.

I mounted it on a German Equatorial from an old Tasco 4 inch reflector a friend gave me. The aluminum pie pan makes the shadow for the projected solar image. To connect the imager to the eyepiece I used black PVC tubing with straightened clothes hanger metal spokes in drilled through holes. The spokes are held in place with a stainless steel tube clamp. Rubber bands behind the white projection plate hold it firmly in place. I use this scope to observe Sun spots. Not only can I see the spots but also sometimes can see the whitish faculae which frequently accompany and surround them!

I finally got the balancing just right for the 12 1/2″ scope. That was tricky! This mount allows me to move the whole assembly with a finger light touch. I made brakes to stop motion A/R in either axis from hard wood cutouts.

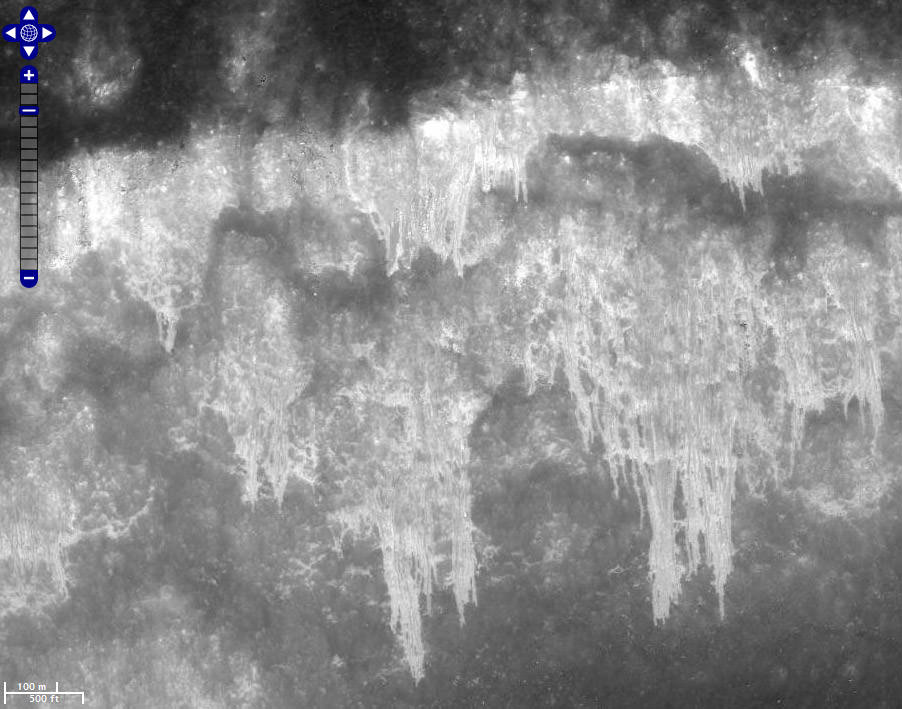

Here’s a view of the secondary mirror housing:

The aluminum struts I purchased at a scrap and hardware store. I made the finder scope from a pair of ‘funky’ plastic Chinese binoculars that never focused properly anyway. The finder’s body and mount are constructed from white PVC tubing and held in place with nylon screws. The base of the finder mount was made from a broken finder scope that I modified to fit with a Dremel tool. The eyepiece focuser can be moved left/right, up/down on any of the four paired dowels by loosening the attached nylon screws. Next up, I will make a ‘clocking mechanism’ so I can easily turn the secondary 90-180 or 270 degrees.

I can add other focusers, cameras or instruments on any of the 4X ‘dowel flat’ pairs. I made the secondary mirror from a precision optical flat another scientist friend gave me back in 1984 when I worked at a semiconductor equipment manufacturing company. Ever cut glass before? Triple trick! Those flats were coated with aluminum during a vacuum/deposition chamber test. The secondary housing I cut from an old fishing rod transport tube. Later, I plan to purchase a 1/10 wave or better secondary and new mirror mount. The spider legs are modified stainless steel packing straps. Both the secondary housing and main mirror housing were made from 34 qt. alum. cook pots! What’s cooking Daddy-O or Momma Mia?!

Here’s a view of the mirror cover I made from a ‘spare’ plant pot saucer. (Don’t tell the wife!) I sewed the ‘grip handles’ into the nylon mounting straps to aid in tightening the straps. Part of the two wooden brake assemblies are also shown in this view:

In this view you can see the ‘yet to be coated’ primary mirror and the ‘at that time’ mostly unpainted secondary mirror housing:

I’ll have the mirror tested and coated soon and plan on using a web cam or DSLR for imaging after I install some sort of clock drive mechanism. I hope to eventually participate in the Universe Today’s weekly online Virtual Star Parties with this ‘puppy’ (as David Letterman would say) when completed. I hope so anyway… only time will tell!

In the next episode… I hope to ‘show off’ some images! There’s that ‘only time will tell’ thing again!

Have any questions or comments for Dale about his amateur DIY astronomy? Leave comments below, or you can send him an email

All images are courtesy Dale Jacobs