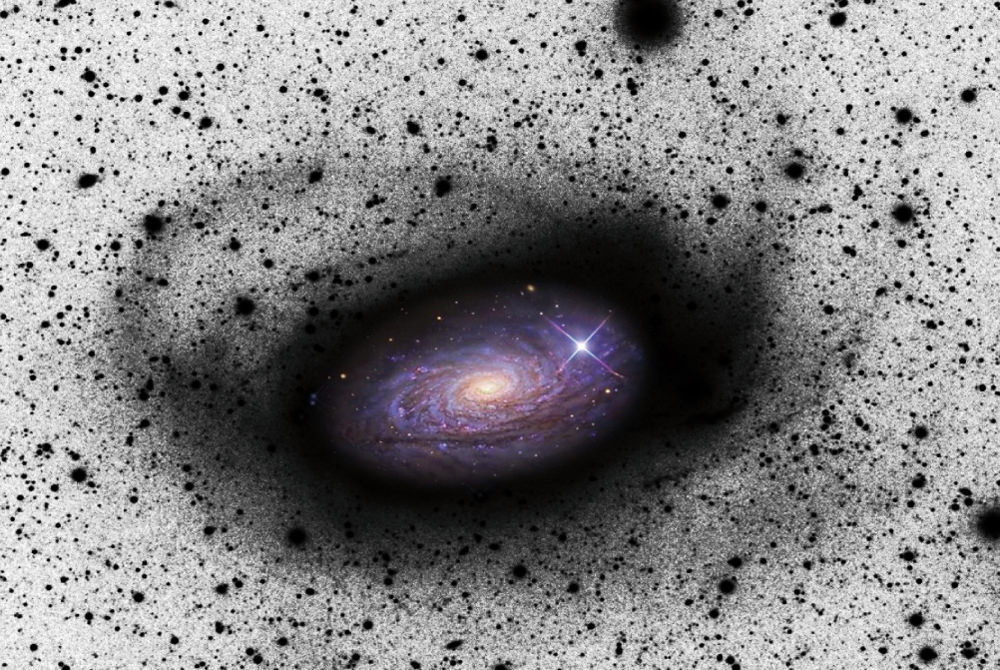

[/caption]

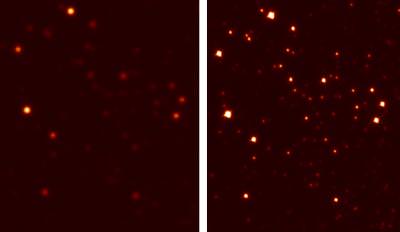

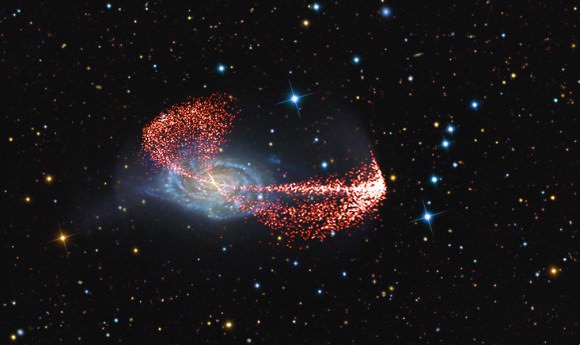

For years, astronomers have seen evidence that – at least in our own local neighborhood — spiral galaxies are consuming smaller dwarf galaxies. As they are digested, these dwarf galaxies are severely distorted, forming structures like strange, looping tendrils and stellar streams that surround the cannibalistic spirals. But now, for the first time, a new survey has detected such tell-tale structures in galaxies more distant than our immediate galactic neighborhood, providing evidence that this galactic cannibalism might take place on a universal scale. Remarkably, these cutting-edge results were obtained with small, amateur-sized telescopes.

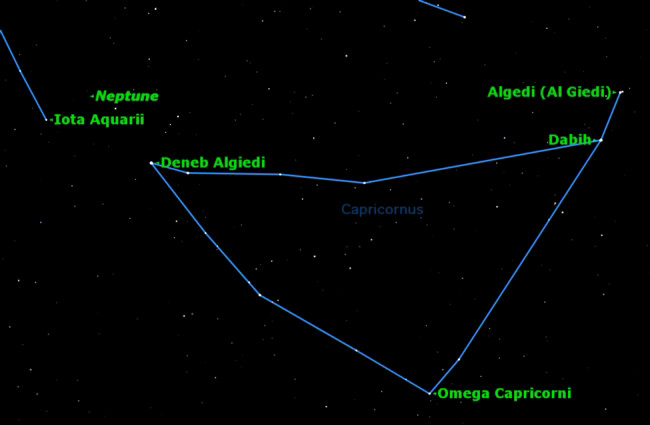

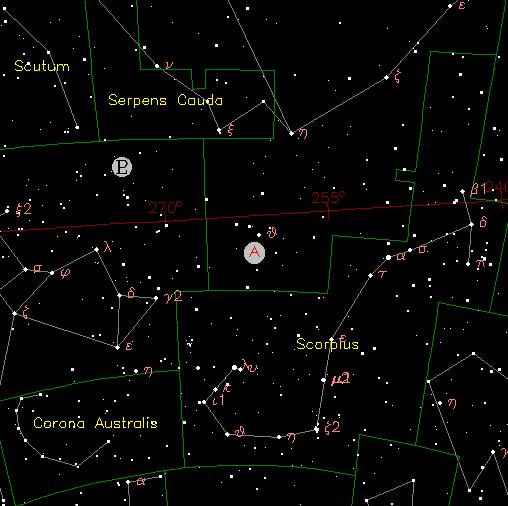

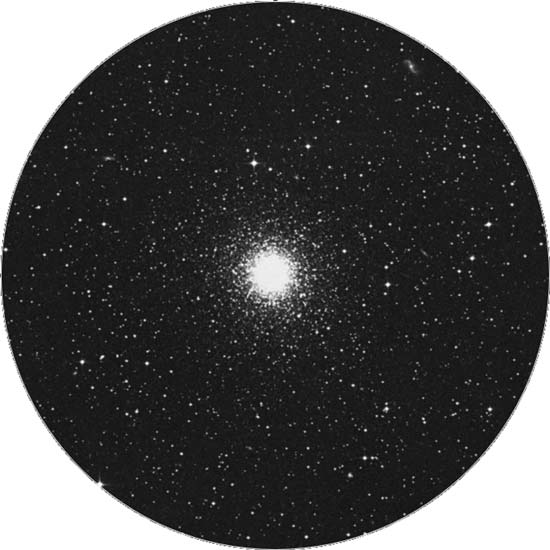

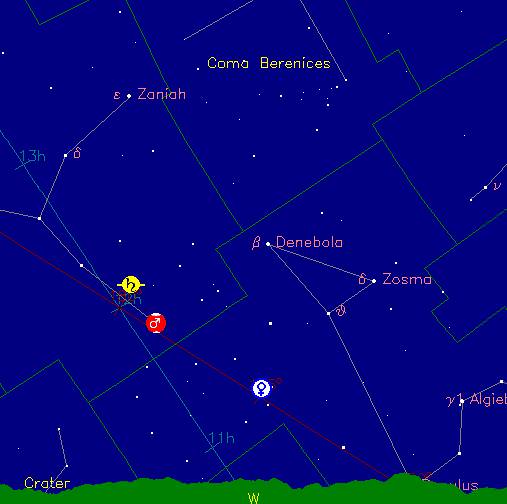

Since 1997, astronomers have seen evidence that spirals in our local group of galaxies are swallowing dwarfs. In fact, our own Milky Way is currently in the process of eating the Canis Major dwarf galaxy and the Sagittarius dwarf galaxy. But the Local group with its three spiral galaxies and numerous dwarfs is much too small a sample to see whether this digestive process is happening elsewhere in the Universe. But an international group of researchers led by David Martínez-Delgado from the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy recently completed a survey of spiral galaxies at distances of up to 50 million light-years from Earth, discovering the tell-tale signs of spirals eating dwarfs.

For their observations, the researchers used small telescopes with apertures between 10 and 50 cm, equipped with commercially available CCD cameras. The telescopes are located at two private observatories — one in the US and one in Australia. They are robotic telescopes that can be controlled remotely.

During the “eating” process, when a spiral galaxy is approached by a much smaller companion, such as a dwarf galaxy, the larger galaxy’s uneven gravitational pull severely distorts the smaller star system. Over the course of a few billions of years, tendril-like structures develop that can be detected by sensitive observation. In one typical outcome, the smaller galaxy is transformed into an elongated “tidal stream” consisting of stars that, over the course of additional billions of years, will join the galaxy’s regular stellar inventory through a process of complete assimilation. The study shows that major tidal streams with masses between 1 and 5 percent of the galaxy’s total mass are quite common in spiral galaxies.

Detailed simulations depicting the evolution of galaxies predict both tidal streams and a number of other distinct features that indicate mergers, such as giant debris clouds or jet-like features emerging from galactic discs. Interestingly, all these various features are indeed seen in the new observations – impressive evidence that current models of galaxy evolution are indeed on the right track.

The ultra-deep images obtained by Delgado and his colleagues open the door to a new round of systematic galactic interaction studies. Next, with a more complete survey that is currently in progress, the researchers intend to subject the current models to more quantitative tests, checking whether current simulations make the correct predictions for the relative frequency of the different morphological features.

While larger telescopes have the undeniable edge in detecting very distant, but comparatively bright star systems such as active galaxies, this survey provides some of the deepest insight yet when it comes to detecting ordinary galaxies that are similar to our own cosmic home, the Milky Way. The results attest to the power of systematic work that is possible even with smaller instruments.

For more images see this page from the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy

*Note: Originally the lead image image was credited incorrectly, and is actually a product of R. Jay Gabany, an astrophotographer whose work has been featured quite often here on Universe Today. See more of his amazing handiwork at his website, Cosmotography.