My attention was focused on beaded water on a poplar leaf. How gemmy and bursting with the morning’s sunlight. I moved closer, removed my glasses and noticed that each drop magnified a little patch of veins that thread and support the leaf.

Focusing the camera lens, I wondered how long it took the drops’ light to reach my eye. Since I was only about six inches away and light travels at 186,000 miles per second or 11.8 inches every billionth of a second (one nanosecond), the travel time amounted to 0.5 nanoseconds. Darn close to simultaneous by human standards but practically forever for positronium hydride, an exotic molecule made of a positron, electron and hydrogen atom. The average lifetime of a PsH molecule is just 0.5 nanoseconds.

In our everyday life, the light from familiar faces, roadside signs and the waiter whose attention you’re trying to get reaches our eyes in nanoseconds. But if you happen to look up to see the tiny dark shape of a high-flying airplane trailed by the plume of its contrail, the light takes about 35,000 nanoseconds or 35 microseconds to travel the distance. Still not much to piddle about.

The space station orbits the Earth in outer space some 250 miles overhead. During an overhead pass, light from the orbiting science lab fires up your retinas 1.3 milliseconds later. In comparison, a blink of the eye lasts about 300 milliseconds (1/3 of a second) or 230 times longer!

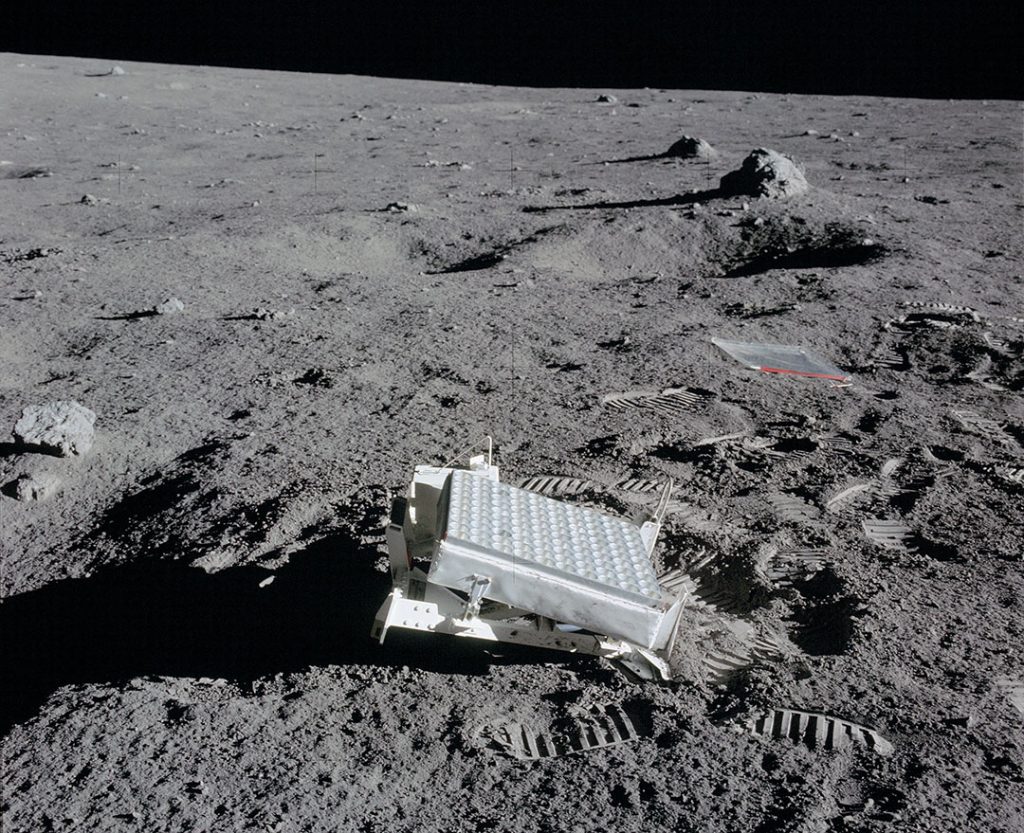

Light time finally becomes more tangible when we look at the Moon, a wistful 1.3 light seconds away at its average distance of 240,000 miles. To feel how long this is, stare at the Moon at the next opportunity and count out loud: one one thousand one. Retroreflecting devices placed on the lunar surface by the Apollo astronauts are still used by astronomers to determine the moon’s precise distance. They beam a laser at the mirrors and time the round trip.

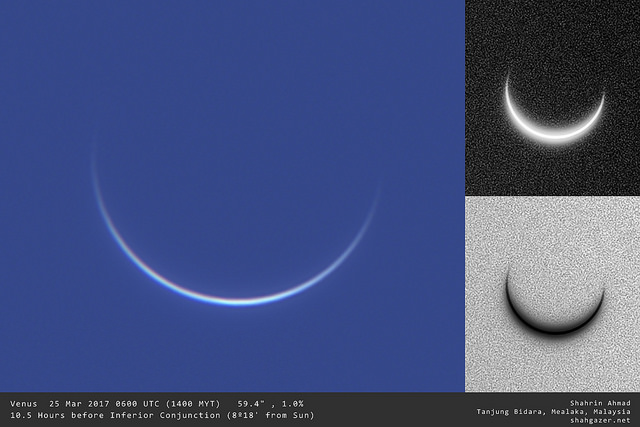

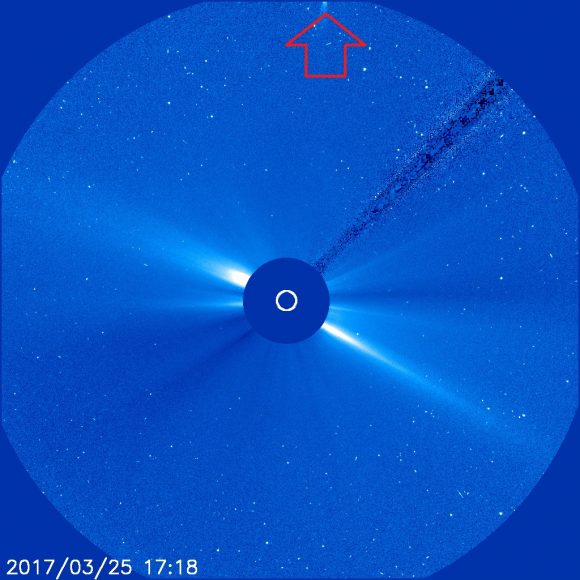

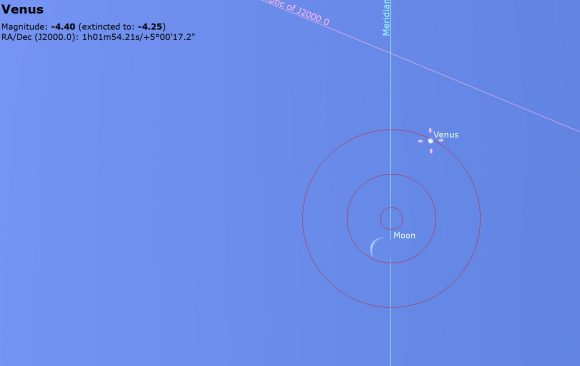

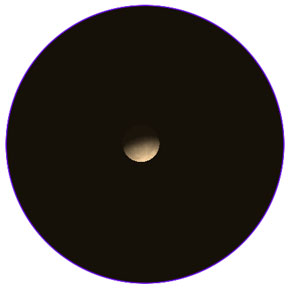

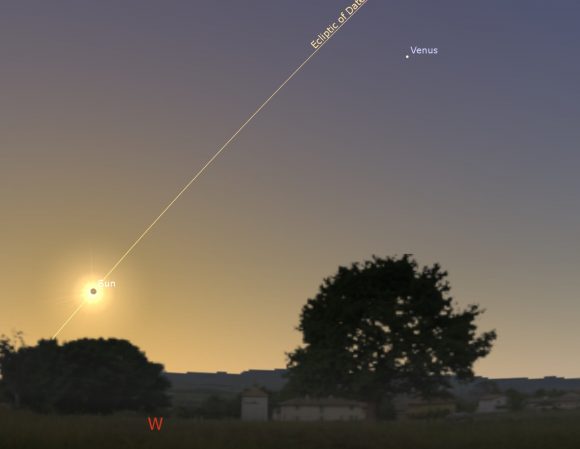

Of the eight planets, Venus comes closest to Earth, and it does so during inferior conjunction, which coincidentally occurred on March 25. On that date only 26.1 million miles separated the two planets, a distance amounting to 140 seconds or 2.3 minutes — about the time it takes to boil water for tea. Mars, another close-approaching planet, currently stands on nearly the opposite side of the Sun from Earth.

With a current distance of 205 million miles, a radio or TV signal, which are both forms of light, broadcast to the Red Planet would take 18.4 minutes to arrive. Now we can see why engineers pre-program a landing sequence into a Mars’ probe’s computer to safely land it on the planet’s surface. Any command – or change in commands – we might send from Earth would arrive too late. Once a lander settles on the planet and sends back telemetry to communicate its condition, mission control personnel must bite their fingernails for many minutes waiting for light to limp back and bring word.

Before we speed off to more distant planets, let’s consider what would happen if the Sun had a catastrophic malfunction and suddenly ceased to shine. No worries. At least not for 8.3 minutes, the time it takes for light, or the lack of it, to bring the bad news.

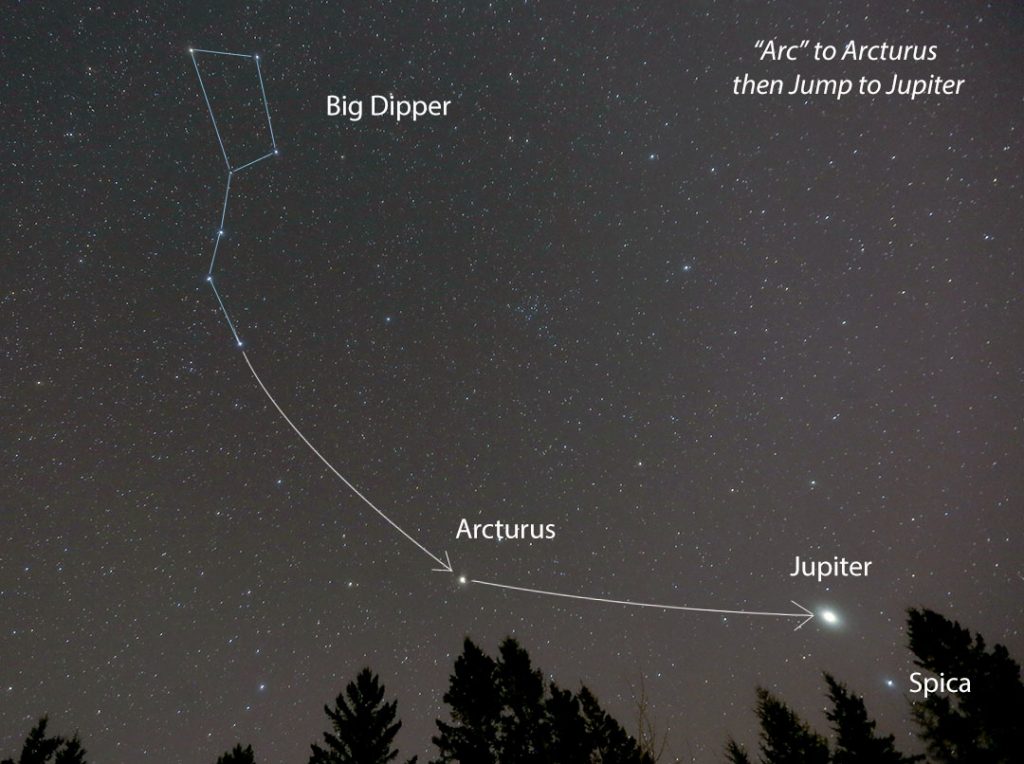

Light from Jupiter takes 37 minutes to reach Earth; Pluto and Charon are so remote that a signal from the “double planet” requires 4.6 hours to get here. That’s more than a half-day of work on the job, and we’ve only made it to the Kuiper Belt.

Let’s press on to the nearest star(s), the Alpha Centauri system. If 4.6 hours of light time seemed a long time to wait, how about 4.3 years? If you think hard, you might remember what you were up to just before New Year’s Eve in 2012. About that time, the light arriving tonight from Alpha Centauri left that star and began its earthward journey. To look at the star then is to peer back in time to late 2012.

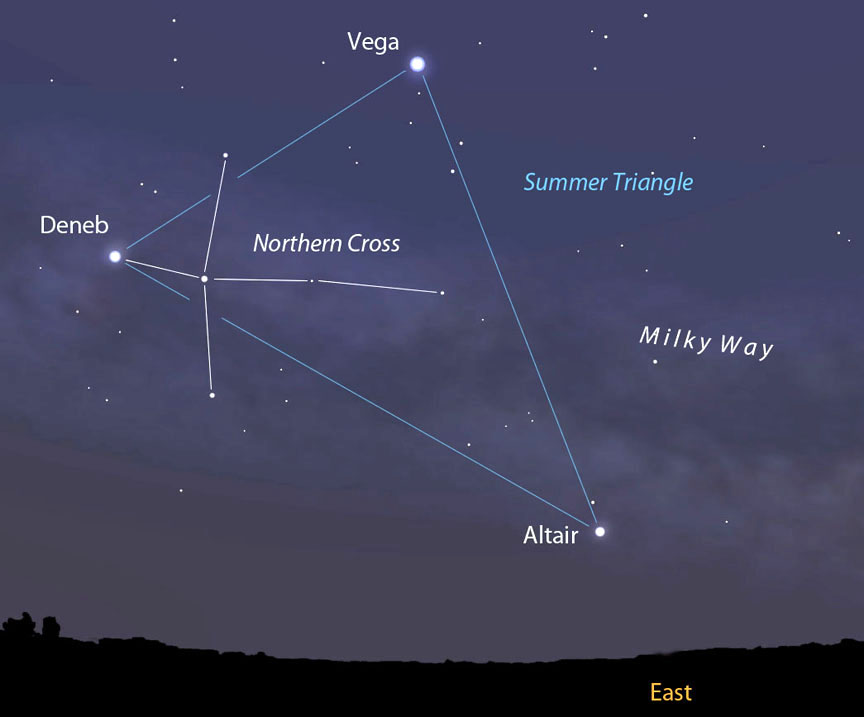

But we barely scrape the surface. Let’s take the Summer Triangle, a figure that will soon come to dominate the eastern sky along with the beautiful summer Milky Way that appears to flow through it. Altair, the southernmost apex of the triangle is nearby, just 16.7 light years from Earth; Vega, the brightest a bit further at 25 and Deneb an incredible 3,200 light years away.

We can relate to the first two stars because the light we see on a given evening isn’t that “old.” Most of us can conjure up an image of our lives and the state of world affairs 16 and 25 years ago. But Deneb is exceptional. Photons departed this distant supergiant (3,200 light years) around the year 1200 B.C. during the Trojan War at the dawn of the Iron Age. That’s some look-back time!

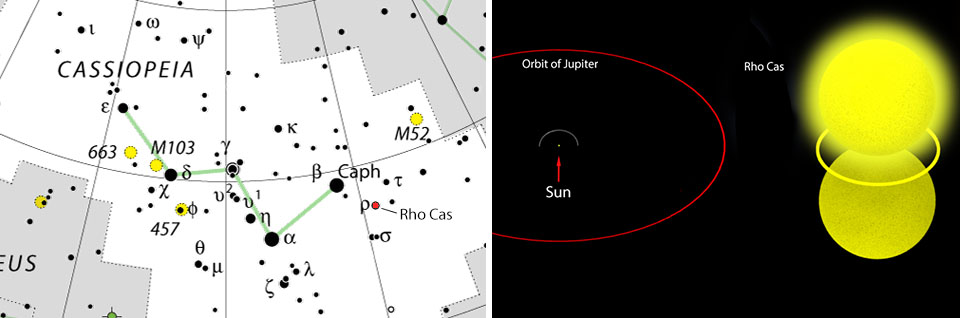

One of the most distant naked eye stars is Rho Cassiopeiae, yellow variable some 450 times the size of the Sun located 8,200 light years away in the constellation Cassiopeia. Right now, the star is near maximum and easy to see at nightfall in the northwestern sky. Its light whisks us back to the end of the last great ice age at a time and the first cave drawings, more than 4,000 years before the first Egyptian pyramid would be built.

On and on it goes: the nearest large galaxy, Andromeda, lies 2.5 million light years from us and for many is the faintest, most distant object visible with the naked eye. To think that looking at the galaxy takes us back to the time our distant ancestors first used simple tools. Light may be the fastest thing in the universe, but these travel times hint at the true enormity of space.

Let’s go a little further. On November 16, 1974 a digital message was beamed from the Arecibo radio telescope in Puerto Rico to the rich star cluster M13 in Hercules 25,000 light years away. The message was created by Dr. Frank Drake, then professor of astronomy at Cornell, and contained basic information about humanity, including our numbering system, our location in the solar system and the composition of DNA, the molecule of life. It consisted of 1,679 binary bits representing ones and zeroes and was our first deliberate communication sent to extraterrestrials. Today the missive is 42 light years away, just barely out the door.

Let’s end our time machine travels with the most distant object we’ve seen in the universe, a galaxy named GN-z11 in Ursa Major. We see it as it was just 400 million years after the Big Bang (13.4 billion years ago) which translates to a proper distance from Earth of 32 billion light years. The light astronomers captured on their digital sensors left the object before there was an Earth, a Solar System or even a Milky Way galaxy!

Thanks to light’s finite speed we can’t help but always see things as they were. You might wonder if there’s any way to see something right now without waiting for the light to get here? There’s just one way, and that’s to be light itself.

Thanks to light’s finite speed we can’t help but always see things as they were. You might wonder if there’s any way to see something right now without waiting for the light to get here? There’s just one way, and that’s to be light itself.

From the perspective of a photon or light particle, which travels at the speed of light, distance and time completely fall away. Everything happens instantaneously and travel time to anywhere, everywhere is zero seconds. In essence, the whole universe becomes a point. Crazy and paradoxical as this sounds, the theory of relativity allows it because an object traveling at the speed of light experiences infinite time dilation and infinite space contraction.

Just something to think about the next time you meet another’s eyes in conversation. Or look up at the stars.