Greetings, fellow SkyWatchers! While the skies don’t change a whole lot from year to year, how you approach astronomy and what you can do with your “astronomy time” certainly does! We begin the weekend with a variable star and a great galaxy. Ready for more? Then why not tackle an historic learning project with Mars? No scope or binoculars? No problem. There’s still lots of cool things you can do when you know where to look! Whenever you’re ready, I’ll see you in the backyard….

Friday, January 8, 2010 – Tonight we begin by celebrating two births – first Johannes Fabricius (1587). In 1616 he returned from the Netherlands with a telescope to observe with his father David, the discoverer of Mira. The father – son team studied sunspots, and Johannes was the first to submit work on the Sun’s rotation. Precisely 300 years later (and on the anniversary of Galileo’s death), Stephen Hawking was born – who went on to become one of the world’s leaders in cosmological theory. Hawking’s belief that the lay person should have access to his work led him to write a series of popular science books in addition to his academic work. The first of these, “A Brief History of Time”, was published on 1 April 1988 by Hawking, his family and friends, and some leading physicists.

Friday, January 8, 2010 – Tonight we begin by celebrating two births – first Johannes Fabricius (1587). In 1616 he returned from the Netherlands with a telescope to observe with his father David, the discoverer of Mira. The father – son team studied sunspots, and Johannes was the first to submit work on the Sun’s rotation. Precisely 300 years later (and on the anniversary of Galileo’s death), Stephen Hawking was born – who went on to become one of the world’s leaders in cosmological theory. Hawking’s belief that the lay person should have access to his work led him to write a series of popular science books in addition to his academic work. The first of these, “A Brief History of Time”, was published on 1 April 1988 by Hawking, his family and friends, and some leading physicists.

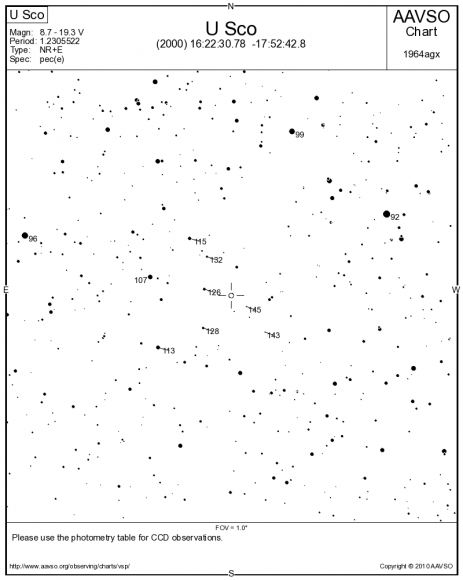

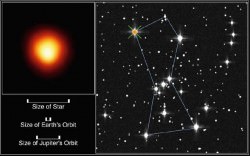

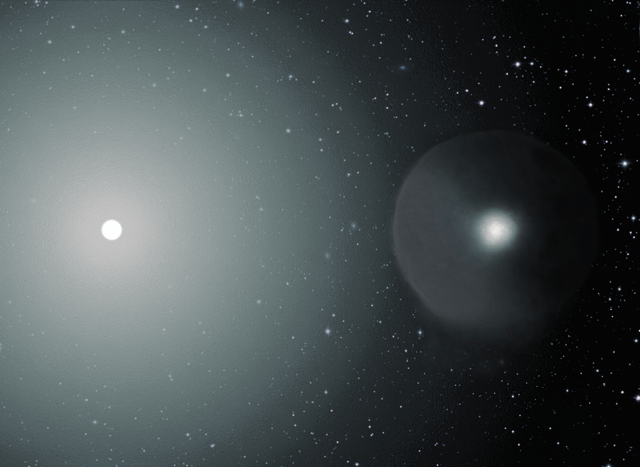

Tonight let’s honor both men as we start with Mira for the unaided eye, binoculars or a telescope. Located in the heart of Cetus the Whale, Mira is one of those variables that even when well placed above the horizon, you can’t always count on it being seen. At its brightest, Mira achieves magnitude 2.0 – bright enough to be seen 10 degrees above the horizon. However Mira “the Wonderful” can also get as faint as magnitude 9 during its 331 day long “heartbeat” cycle of expansion and contraction. Mira is regarded as a premiere study for amateur astronomers interested in beginning variable star observations. For more information about this fascinating and scientifically useful branch of amateur astronomy contact the AAVSO (American Association of Variable Star Observers).

Tonight let’s honor both men as we start with Mira for the unaided eye, binoculars or a telescope. Located in the heart of Cetus the Whale, Mira is one of those variables that even when well placed above the horizon, you can’t always count on it being seen. At its brightest, Mira achieves magnitude 2.0 – bright enough to be seen 10 degrees above the horizon. However Mira “the Wonderful” can also get as faint as magnitude 9 during its 331 day long “heartbeat” cycle of expansion and contraction. Mira is regarded as a premiere study for amateur astronomers interested in beginning variable star observations. For more information about this fascinating and scientifically useful branch of amateur astronomy contact the AAVSO (American Association of Variable Star Observers).

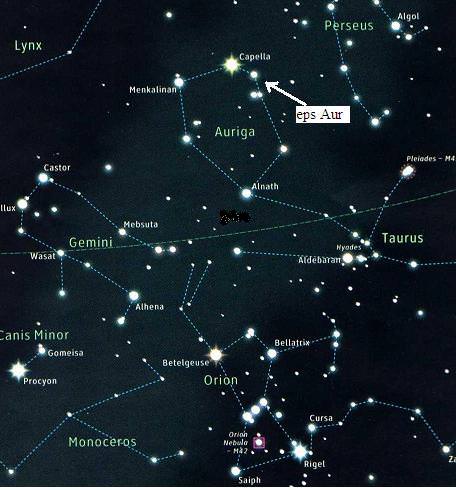

Now for the black hole! All you’ll need to do is starhop about three fingerwidths northeast of Mira to Delta Ceti. About one degree to the southeast you will discover M77. At magnitude 10, this bright, compact spiral galaxy can even be spotted with larger binoculars as a faint glow and is unmistakable as a galaxy in smaller scopes. Its small bright nucleus shows well in mid-sized scopes, while larger ones will resolve out three distinctive spiral arms. But this “Seyfert” Galaxy isn’t alone… If you are using a larger scope, be sure to look for 11th magnitude edge-on companion NGC 1055 about half a degree to the north-northeast, and fainter NGC 1087 and NGC 1090 about a degree to the east-southeast. All are part of a small group of galaxies associated with the 60 million light-year distant M77.

Now for the black hole! All you’ll need to do is starhop about three fingerwidths northeast of Mira to Delta Ceti. About one degree to the southeast you will discover M77. At magnitude 10, this bright, compact spiral galaxy can even be spotted with larger binoculars as a faint glow and is unmistakable as a galaxy in smaller scopes. Its small bright nucleus shows well in mid-sized scopes, while larger ones will resolve out three distinctive spiral arms. But this “Seyfert” Galaxy isn’t alone… If you are using a larger scope, be sure to look for 11th magnitude edge-on companion NGC 1055 about half a degree to the north-northeast, and fainter NGC 1087 and NGC 1090 about a degree to the east-southeast. All are part of a small group of galaxies associated with the 60 million light-year distant M77.

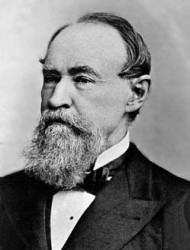

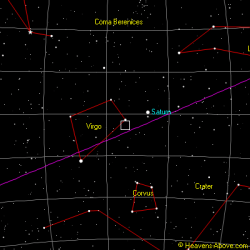

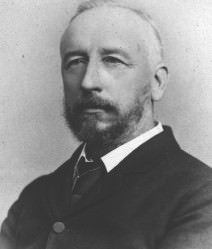

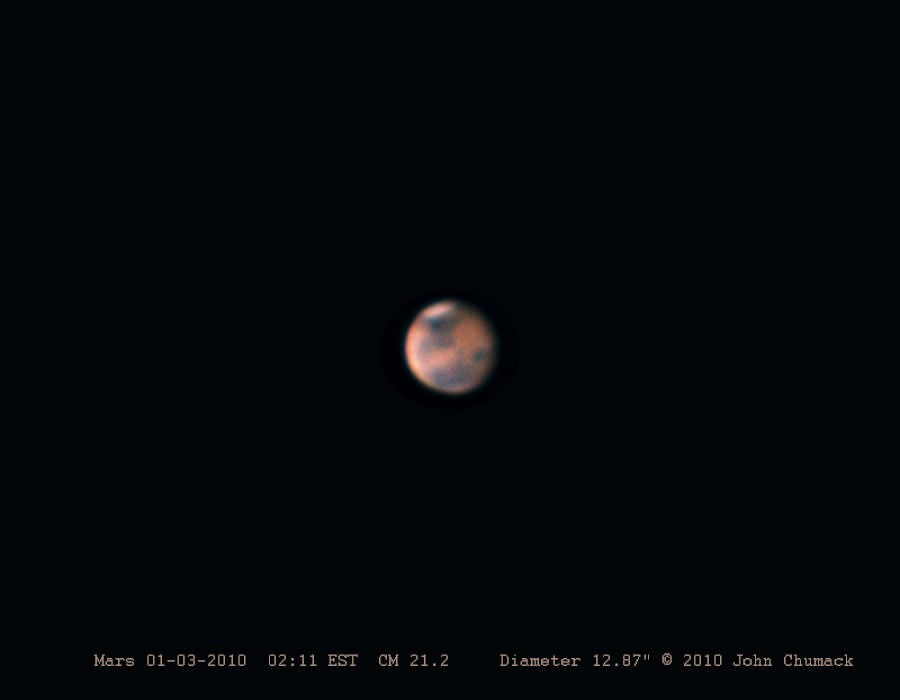

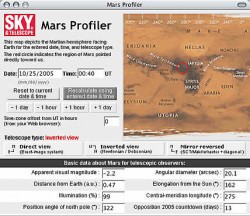

Saturday, January 9, 2010 – Tonight we’re all about Mars. We have precisely 3 weeks to go until opposition – meaning Mars rises as the Sun sets and will be visible all night. This means the Red Planet is very well placed for observing at a convenient time and it’s high time we learned to do some things the “old fashioned way”! Every couple of years Mars comes close enough to Earth for amateur astronomers to do something interesting… measure its distance from Earth using the original method of parallax. The first experiment first carried out by David Gill in 1877 on Ascension Island and now we can do the same from our own backyard. But let’s start with a little history, shall we?

Saturday, January 9, 2010 – Tonight we’re all about Mars. We have precisely 3 weeks to go until opposition – meaning Mars rises as the Sun sets and will be visible all night. This means the Red Planet is very well placed for observing at a convenient time and it’s high time we learned to do some things the “old fashioned way”! Every couple of years Mars comes close enough to Earth for amateur astronomers to do something interesting… measure its distance from Earth using the original method of parallax. The first experiment first carried out by David Gill in 1877 on Ascension Island and now we can do the same from our own backyard. But let’s start with a little history, shall we?

Gill was originally a watchmaker and his love of precision instruments led him into astronomy. Even in those times, employment was scarce… So Gill and his wife set out for Ascension Island to improve the Observatory and measure the solar parallax by observing Mars. But, as all astronomers know, you don’t make a date with the sky – it makes a date with you… and things weren’t about to go easy. From Mrs. Gill’s journal:

Gill was originally a watchmaker and his love of precision instruments led him into astronomy. Even in those times, employment was scarce… So Gill and his wife set out for Ascension Island to improve the Observatory and measure the solar parallax by observing Mars. But, as all astronomers know, you don’t make a date with the sky – it makes a date with you… and things weren’t about to go easy. From Mrs. Gill’s journal:

“Tonight Mars will be nearer to us – his ruddy glare brighter than ever again for a hundred years, and what if we should not see him? The sun had shone all day in a cloudless sky, but before sunset some ugly clouds rolled up from windward… Six o’clock, and still the heavens look undecided; half-past six, and a heavy cloud is forming in the south. Slowly the cloud rises – very slowly; but by-and-by a streak of light rests on the top of the dark rocks – it widens and brightens, and at last we see Mars shining steadily in the pure blue horizon beneath… How slowly the minutes passed! How very long each little interruption appeared! The wind was blowing lazily, and light clouds glided at intervals across the sky, obscuring, for a few moments, the Planet as they crossed his path. But at last I heard the welcome note “All right,” and then I went to bed, leaving David to add the pleasant postscript of “Evening success” to his letters. When the letters were finished, he gave them in charge to Hill, with orders that they should be sent off at daybreak, and then he lay down to rest.

I now took the watch for the morning. The first hours of my waiting promised well, but before 1 A.M. a tiny cloud, no bigger than a man’s hand, arose in the south, and I called my husband to know what he thought of it. On this, the night of Opposition, the planet would be in the most favourable position for beginning morning observations about 2.30. Now it was but 12.50, and the question came to be—shall some value of position be lost, so as to give a greater chance of securing observations before the rising cloud reach the zenith, or shall we wait, in the hope that this cloud has “no followers”? David began work at once in a break-neck position, with the telescope pointed but a few degrees west of the zenith. How my heart beat, for I saw the cloud rise and swell, and yet no silver lining below. I dared not go inside the Observatory, lest my uncontrollable fidgets might worry the observer, but sat without on a heap of clinker, and kept an eye on the enemy. Five, ten, fifteen minutes! Then David called out, “Half set finished—splendid definition—go to bed!” Just in time, I thought, and crept off to my tent, thankful for little, and not expecting more, for one arm of the black cloud was already grasping Mars.

My husband would, of course, remain in the Observatory for the rest of the night to watch for clear intervals, while I was expected to go to sleep. But how could I? I took up a book and tried to read by the light of my lantern for a few minutes; then I thought to myself, “Just a peep to see whether the cloud promises to clear off.” I looked forth, and lo! no cloud! I rubbed my eyes, thinking I must be dreaming, and pulled out my watch, to make sure I had not been asleep, so sudden was the change. No! truly the obnoxious cloud had mysteriously vanished, and the whole moonless heavens were of that inky blueness so dear to astronomers. While my eyes drank in this beautiful scene, my ears were filled with sweet sounds issuing from the Observatory, “A, seventy and one, point two seven one; B, seventy-seven, one, point three six eight,” Let not any one smile that I call these sweet sounds. Sweet they were indeed to me, for they told of success after bitter disappointment; of cherished hopes realised; of care and anxiety passing away. They told too of honest work honestly done – of work that would live and tell its tale, when we and the instruments were no more; and, as I thought of this, there came upon me with all their force the glowing words of Herschel: “When once a place has been thoroughly ascertained, and carefully recorded, the brazen circle with which that useful work was done may moulder, the marble pillar totter on its base, and the astronomer himself survive only in the gratitude of his posterity; but the record remains, and transfuses all its own exactness into every determination which takes it for a groundwork.”

My husband would, of course, remain in the Observatory for the rest of the night to watch for clear intervals, while I was expected to go to sleep. But how could I? I took up a book and tried to read by the light of my lantern for a few minutes; then I thought to myself, “Just a peep to see whether the cloud promises to clear off.” I looked forth, and lo! no cloud! I rubbed my eyes, thinking I must be dreaming, and pulled out my watch, to make sure I had not been asleep, so sudden was the change. No! truly the obnoxious cloud had mysteriously vanished, and the whole moonless heavens were of that inky blueness so dear to astronomers. While my eyes drank in this beautiful scene, my ears were filled with sweet sounds issuing from the Observatory, “A, seventy and one, point two seven one; B, seventy-seven, one, point three six eight,” Let not any one smile that I call these sweet sounds. Sweet they were indeed to me, for they told of success after bitter disappointment; of cherished hopes realised; of care and anxiety passing away. They told too of honest work honestly done – of work that would live and tell its tale, when we and the instruments were no more; and, as I thought of this, there came upon me with all their force the glowing words of Herschel: “When once a place has been thoroughly ascertained, and carefully recorded, the brazen circle with which that useful work was done may moulder, the marble pillar totter on its base, and the astronomer himself survive only in the gratitude of his posterity; but the record remains, and transfuses all its own exactness into every determination which takes it for a groundwork.”

Gill’s work with Mars was such a success that it redetermined the distance to the sun to such precision that his value was used for almanacs until 1968. He went on to photograph the southern sky and helped initiate the international Carte du Ciel project to chart the entire sky. Now, thanks to the efforts of Brian Sheen of Roseland Observatory and John Clark Astronomy, you can easily participate in the same kind of historic project or get the correct information to “do it yourself” with your classroom or astronomy club.

Gill’s work with Mars was such a success that it redetermined the distance to the sun to such precision that his value was used for almanacs until 1968. He went on to photograph the southern sky and helped initiate the international Carte du Ciel project to chart the entire sky. Now, thanks to the efforts of Brian Sheen of Roseland Observatory and John Clark Astronomy, you can easily participate in the same kind of historic project or get the correct information to “do it yourself” with your classroom or astronomy club.

The project involves photographing Mars and nearby stars – images taken at the same time from a number of different locations around the globe. John Clark is prepared to undertake the mathematical analysis or will provide the method for those wishing to do this themselves. All they are asking is for those groups and individuals who normally take images of stars and planets to contact the Observatory and they will provide you will all the detailed information to get in on the Mars action!

The project involves photographing Mars and nearby stars – images taken at the same time from a number of different locations around the globe. John Clark is prepared to undertake the mathematical analysis or will provide the method for those wishing to do this themselves. All they are asking is for those groups and individuals who normally take images of stars and planets to contact the Observatory and they will provide you will all the detailed information to get in on the Mars action!

Sunday, January 10, 2010 – On this date in 1946, Lt. Col. John DeWitt, a handful of full-time researchers, and the U.S. Army’s Signal Corps were about to become the first group to successfully employ radar to bounce radio waves off the Moon. It might sound like a minor achievement, but let’s look into what it really meant.

Believed impossible at the time, scientists were hard at work trying to find a way to pierce Earth’s ionosphere with radio waves. Project Diana used a modified SCR-271 bedspring radar antenna aimed at the rising Moon. Radar signals were broadcast, and the echo was picked up in exactly 2.5 seconds. Discovering that communication was possible through the ionosphere opened the way to space exploration. Although a decade would pass before the first satellites were launched into space, Project Diana paved the way for these achievements, so send your own ‘‘wave’’ to the late rising Moon tonight!

Believed impossible at the time, scientists were hard at work trying to find a way to pierce Earth’s ionosphere with radio waves. Project Diana used a modified SCR-271 bedspring radar antenna aimed at the rising Moon. Radar signals were broadcast, and the echo was picked up in exactly 2.5 seconds. Discovering that communication was possible through the ionosphere opened the way to space exploration. Although a decade would pass before the first satellites were launched into space, Project Diana paved the way for these achievements, so send your own ‘‘wave’’ to the late rising Moon tonight!

Let’s also note the 1936 birth of Robert W. Wilson, the co-discoverer (along with Arno Penzias) of the cosmic microwave background. Although the discovery was a bit of a fluke, Wilson’s penchant for radio was no secret. As he once said, ‘‘I built my own hi-fi set and enjoyed helping friends with their amateur radio transmitters, but lost interest as soon as they worked.’’ But don’t you loose interest in the night sky! Even if you don’t use a telescope or binoculars, you can still look towards Cassiopeia, which contains the strongest known radio source in our own galaxy – Cassiopeia A.

Let’s also note the 1936 birth of Robert W. Wilson, the co-discoverer (along with Arno Penzias) of the cosmic microwave background. Although the discovery was a bit of a fluke, Wilson’s penchant for radio was no secret. As he once said, ‘‘I built my own hi-fi set and enjoyed helping friends with their amateur radio transmitters, but lost interest as soon as they worked.’’ But don’t you loose interest in the night sky! Even if you don’t use a telescope or binoculars, you can still look towards Cassiopeia, which contains the strongest known radio source in our own galaxy – Cassiopeia A.

Although traces of the 300-year-old supernova can no longer be seen in visible light, radiation noise still emanates from 10,000 light-years away – an explosion still expanding at 16 million kilometers per hour! So, where is the source of this radio beauty? Just a little bit north of the constellation’s center star.

Until next week? Have fun learning!

This week’s awesome image (in order of appearance) are: Stephen Hawking (public domain photo), Mira courtesy of SEDS (contributed by Jack Schmidling), M77 courtesy of NOAO/AURA/NSF, David Gill (historic image), Mars Hubble Photo, Ascension Island Map (Library on Congress – David Weaver), Mars Retrograde Animation courtesy of Arizona State University, Mars Horizon Map courtesy of Your Sky, Project Diana (public domain image), Cassiopeia A courtesy of Spitzer. We thank you so much!