Omega Centauri is a strange thing. It’s been classified as a star, then a nebula, then a globular cluster and now it’s thought to be a dwarf galaxy missing its outer stars. Why is it in such a mess? How can this oddball galaxy be explained? New research suggests it has an intermediate-black hole living in its core, giving astronomers the best idea yet as to where supermassive black holes come from. Omega Centauri might hold one of the most profound secrets as to how the largest objects in the observable universe are born…

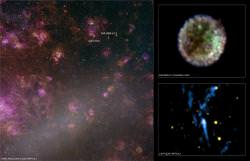

Two thousand years ago, Omega Centauri was classified as a single star by Ptolemy. Edmond Halley studied this “star” but thought it looked a bit diffuse and re-classified it as a nebula in 1677. Then, in the 1830s, John Herschel was the first astronomer to realize this “nebula” was actually a galaxy, a globular cluster galaxy. But now, new observations by the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) reveal that this “globular cluster” isn’t what it seems… it’s actually a dwarf galaxy, stripped of its outer stars, some 17,000 light years away.

See an observation video zooming into the location of Omega Centauri in the constellation of Centaurus.

So what led to astronomers thinking there was something strange about this cosmic collection of stars? It rotates faster than other globular clusters, it is strangely flat and it contains stars of many generations (globular clusters usually contain stars of one generation). These reasons plus the fact Omega Centauri is ten times bigger than the largest globular clusters have led scientists to believe that this was no ordinary galaxy.

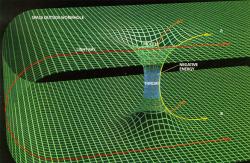

The main theory is that this unlucky galaxy may have crashed into the Milky Way in the distant past, shedding its outermost stars during the collision. This explains the lack of stars in its outer region. But why is it rotating so quickly, especially in the center?

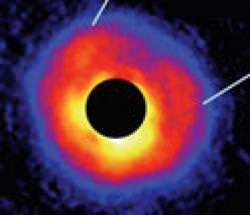

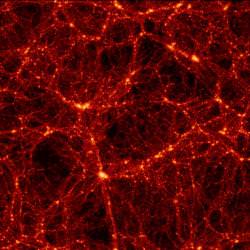

These stunning images were taken by the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope, which continues to do amazing science after 18 years in orbit. Combined with ground-based observations by the Gemini South telescope in Chile, astronomers have been able to deduce that a black hole may be at the root of a lot of the anomalies seen in Omega Centauri.

The research carried out at the Max-Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics (in Garching, Germany), headed by Eva Noyola, shows stars near the center of Omega Centauri orbiting something very fast. In fact, this something is invisible for a reason. Calculating this invisible object’s mass, it is most likely that the group are observing an intermediate-size black hole with the mass of 40,000 solar masses. They have investigated other possibilities, perhaps the fast-orbiting stars could be accelerated by the collective mass of small, weakly radiating bodies such as white dwarves, or the orbiting stars’ have highly elliptical orbits and the point of closest approach is currently being observed, giving the impression they are going faster. However, the intermediate-size black hole theory appears to fit the situation far better.

This is a highly significant discovery, as so far there has been little linking the smaller, stellar black holes with the supermassive ones that sit in the center of large galaxies such as our own. There have been many theories put forward about how these huge black holes may have formed, but to find an intermediate-sized black hole may be the missing link and will help astrophysicists understand how supermassive black holes are “seeded” in the first place.

“This result shows that there is a continuous range of masses for black holes, from supermassive, to intermediate-mass, to small stellar mass types […] We may be on the verge of uncovering one possible mechanism for the formation of supermassive black holes. Intermediate-mass black holes like this could be the seeds of full-sized supermassive black holes.” – Eva Noyola.

Source: SpaceTelescope.org