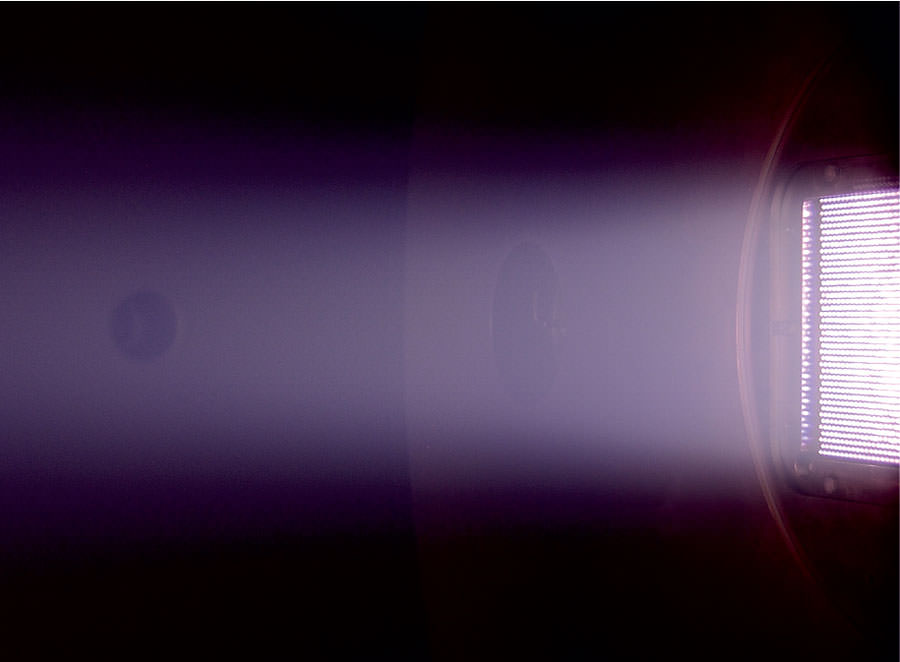

Plasma propulsion is a subject of keen interest to astronomers and space agencies. As a highly-advanced technology that offers considerable fuel-efficiency over conventional chemical rockets, it is currently being used in everything from spacecraft and satellites to exploratory missions. And looking to the future, flowing plasma is also being investigated for more advanced propulsion concepts, as well as magnetic-confined fusion.

However, a common problem with plasma propulsion is the fact that it relies on what is known as a “neutralizer”. This instrument, which allows spacecraft to remain charge-neutral, is an additional drain on power. Luckily, a team of researchers from the University of York and École Polytechnique are investigating a plasma thruster design that would do away with a neutralizer altogether.

A study detailing their research findings – titled “Transient propagation dynamics of flowing plasmas accelerated by radio-frequency electric fields” – was released earlier this month in Physics of Plasmas – a journal published by the American Institute of Physics. Led by Dr. James Dendrick, a physicist from the York Plasma Institute at the University of York, they present a concept for a self-regulating plasma thruster.

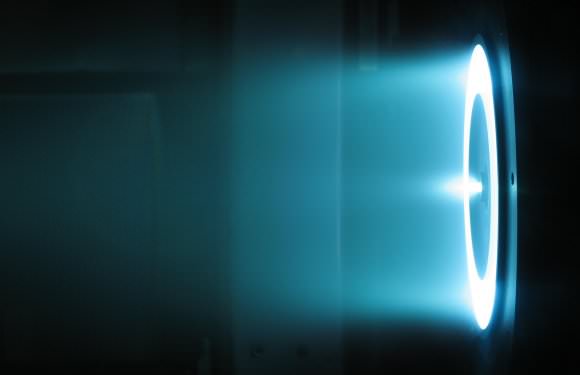

Basically, plasma propulsion systems rely on electric power to ionize propellant gas and transform it into plasma (i.e. negatively charged electrons and positively-charged ions). These ions and electrons are then accelerated by engine nozzles to generate thrust and propel a spacecraft. Examples include the Gridded-ion and Hall-effect thruster, both of which are established propulsion technologies.

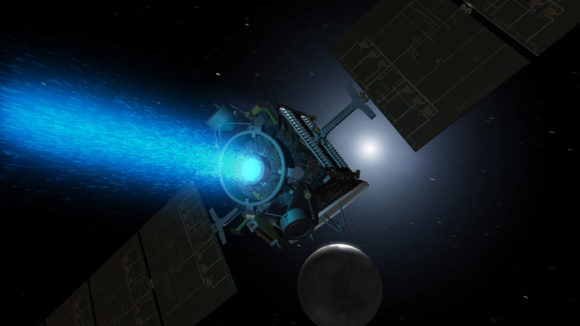

The Gridden-ion thruster was first tested in the 1960s and 70s as part of the Space Electric Rocket Test (SERT) program. Since then, it has been used by NASA’s Dawn mission, which is currently exploring Ceres in the Main Asteroid Belt. And in the future, the ESA and JAXA plan to use Gridded-iron thrusters to propel their BepiColombo mission to Mercury.

Similarly, Hall-effect thrusters have been investigated since the 1960s by both NASA and the Soviet space programs. They were first used as part of the ESA’s Small Missions for Advanced Research in Technology-1 (SMART-1) mission. This mission, which launched in 2003 and crashed into the lunar surface three years later, was the first ESA mission to go to the Moon.

As noted, spacecraft that use these thrusters all require a neutralizer to ensure that they remain “charge-neutral”. This is necessary since conventional plasma thrusters generate more positively-charged particles than they do negatively-charged ones. As such, neutralizers inject electrons (which carry a negative charge) in order to maintain the balance between positive and negative ions.

As you might suspect, these electrons are generated by the spacecraft’s electrical power systems, which means that the neutralizer is an additional drain on power. The addition of this component also means that the propulsion system itself will have to be larger and heavier. To address this, the York/École Polytechnique team proposed a design for a plasma thruster that can remain charge neutral on its own.

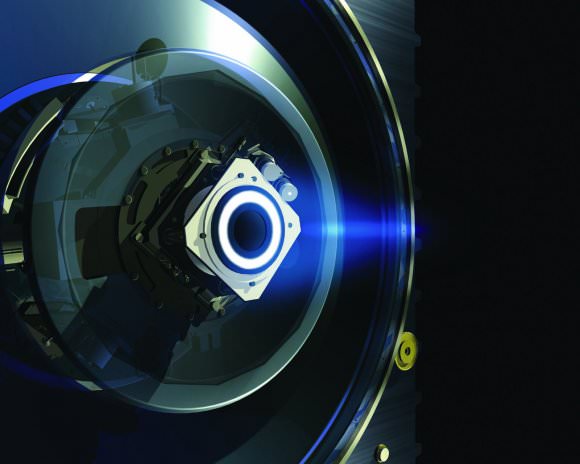

Known as the Neptune engine, this concept was first demonstrated in 2014 by Dmytro Rafalskyi and Ane Aanesland, two researchers from the École Polytechnique’s Laboratory of Plasma Physics (LPP) and co-authors on the recent paper. As they demonstrated, the concept builds upon the technology used to create gridded-ion thrusters, but manages to generate exhaust that contains comparable amounts of positively and negatively charged ions.

As they explain in the course of their study:

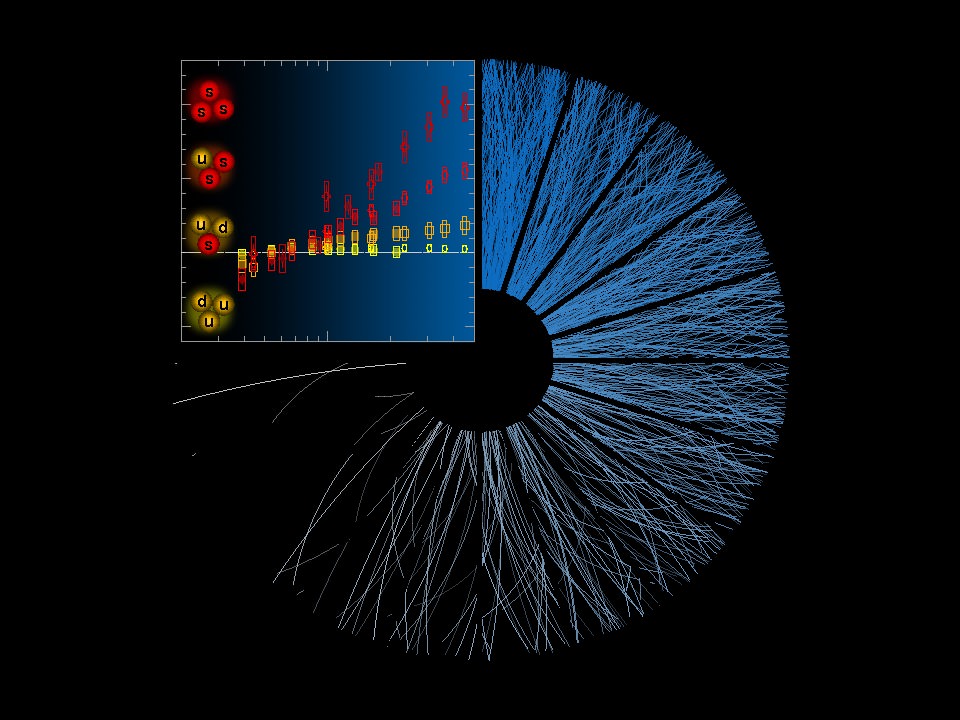

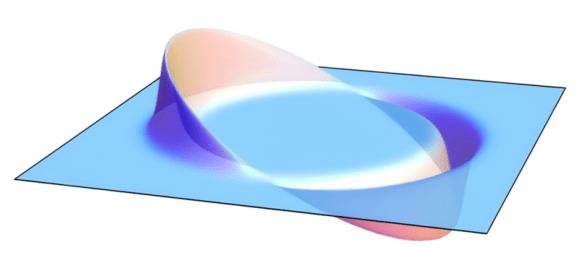

“Its design is based on the principle of plasma acceleration, whereby the coincident extraction of ions and electrons is achieved by applying an oscillating electrical field to the gridded acceleration optics. In traditional gridded-ion thrusters, ions are accelerated using a designated voltage source to apply a direct-current (dc) electric field between the extraction grids. In this work, a dc self-bias voltage is formed when radio-frequency (rf) power is coupled to the extraction grids due to the difference in the area of the powered and grounded surfaces in contact with the plasma.”

In short, the thruster creates exhaust that is effectively charge-neutral through the application of radio waves. This has the same effect of adding an electrical field to the thrust, and effectively removes the need for a neutralizer. As their study found, the Neptune thruster is also capable of generating thrust that is comparable to a conventional ion thruster.

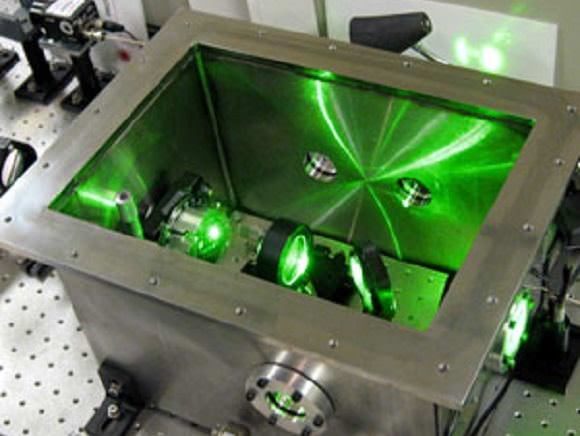

To advance the technology even further, they teamed up with James Dedrick and Andrew Gibson from the York Plasma Institute to study how the thruster would work under different conditions. With Dedrick and Gibson on board, they began to study how the plasma beam might interact with space and whether this would affect its balanced charge.

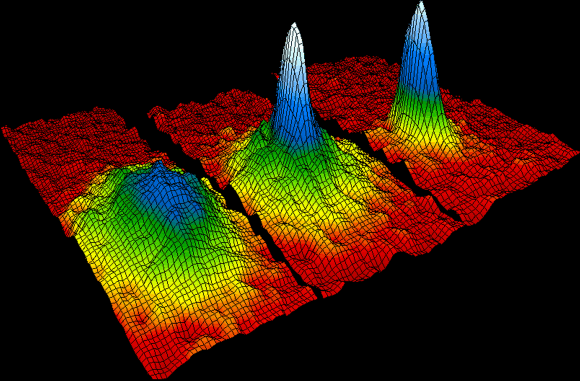

What they found was that the engine’s exhaust beam played a large role in keeping the beam neutral, where the propagation of electrons after they are introduced at the extraction grids acts to compensate for space-charge in the plasma beam. As they state in their study:

“[P]hase-resolved optical emission spectroscopy has been applied in combination with electrical measurements (ion and electron energy distribution functions, ion and electron currents, and beam potential) to study the transient propagation of energetic electrons in a flowing plasma generated by an rf self-bias driven plasma thruster. The results suggest that the propagation of electrons during the interval of sheath collapse at the extraction grids acts to compensate space-charge in the plasma beam.”

Naturally, they also emphasize that further testing will be needed before a Neptune thruster can ever be used. But the results are encouraging, since they offer up the possibility of ion thrusters that are lighter and smaller, which would allow for spacecraft that are even more compact and energy-efficient. For space agencies looking to explore the Solar System (and beyond) on a budget, such technology is nothing if not desirable!

Further Reading: Physics of Plasmas, AIP