What if it were possible to observe the fundamental building blocks upon which the Universe is based? Not a problem! All you would need is a massive particle accelerator, an underground facility large enough to cross a border between two countries, and the ability to accelerate particles to the point where they annihilate each other – releasing energy and mass which you could then observe with a series of special monitors.

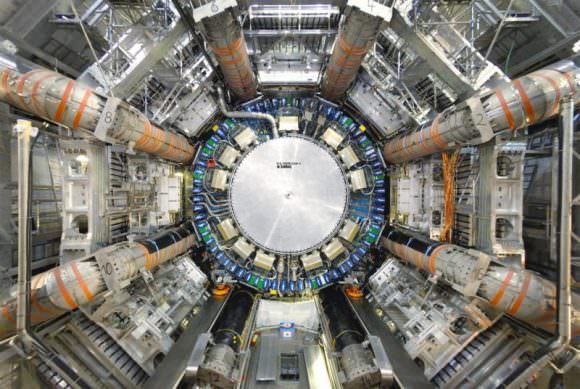

Well, as luck would have it, such a facility already exists, and is known as the CERN Large Hardron Collider (LHC), also known as the CERN Particle Accelerator. Measuring roughly 27 kilometers in circumference and located deep beneath the surface near Geneva, Switzerland, it is the largest particle accelerator in the world. And since CERN flipped the switch, the LHC has shed some serious light on some deeper mysteries of the Universe.

Purpose:

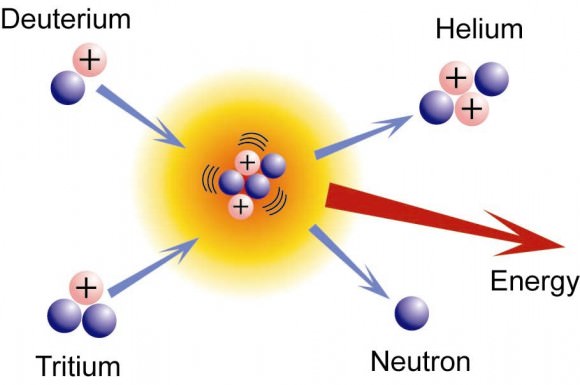

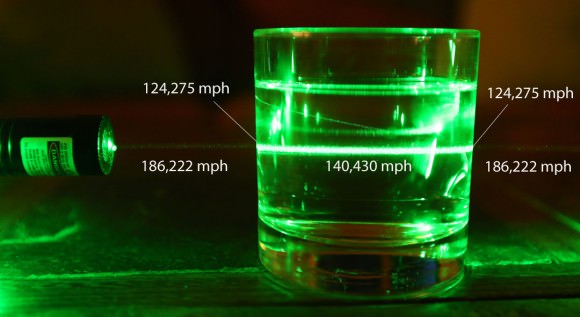

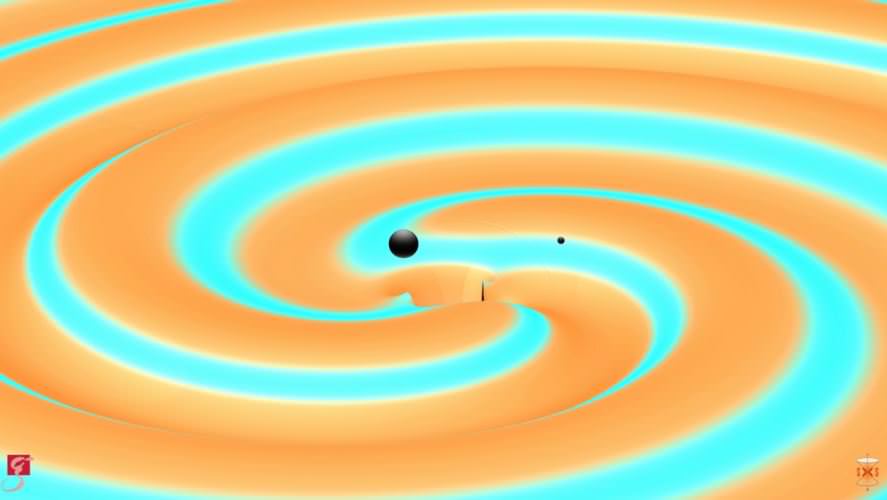

Colliders, by definition, are a type of a particle accelerator that rely on two directed beams of particles. Particles are accelerated in these instruments to very high kinetic energies and then made to collide with each other. The byproducts of these collisions are then analyzed by scientists in order ascertain the structure of the subatomic world and the laws which govern it.

The purpose of colliders is to simulate the kind of high-energy collisions to produce particle byproducts that would otherwise not exist in nature. What’s more, these sorts of particle byproducts decay after very short period of time, and are are therefor difficult or near-impossible to study under normal conditions.

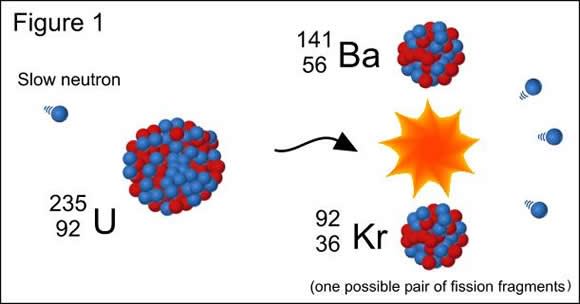

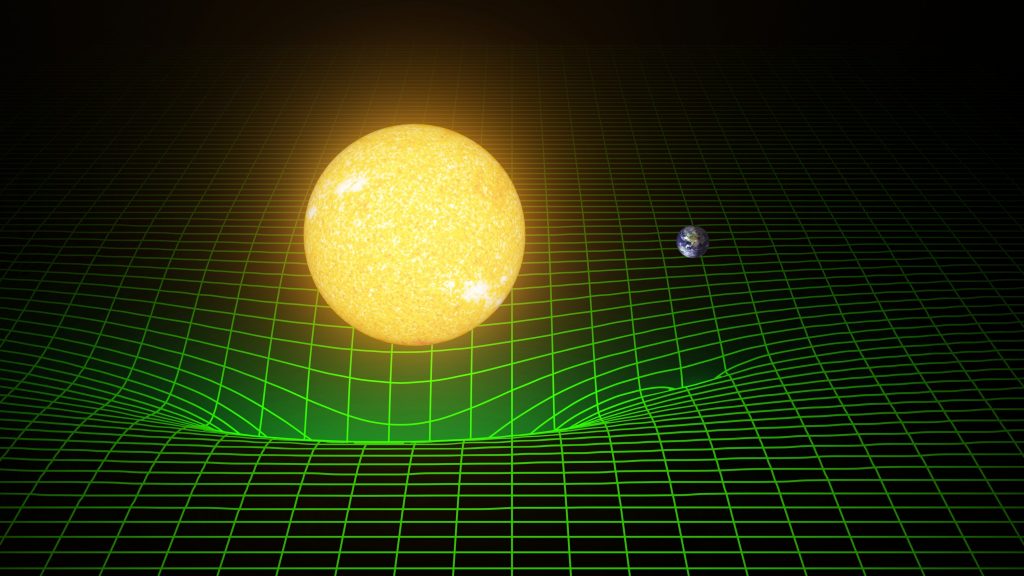

The term hadron refers to composite particles composed of quarks that are held together by the strong nuclear force, one of the four forces governing particle interaction (the others being weak nuclear force, electromagnetism and gravity). The best-known hadrons are baryons – protons and neutrons – but also include mesons and unstable particles composed of one quark and one antiquark.

Design:

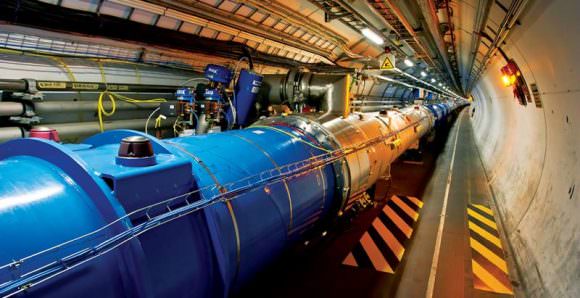

The LHC operates by accelerating two beams of “hadrons” – either protons or lead ions – in opposite directions around its circular apparatus. The hadrons then collide after they’ve achieved very high levels of energy, and the resulting particles are analyzed and studied. It is the largest high-energy accelerator in the world, measuring 27 km (17 mi) in circumference and at a depth of 50 to 175 m (164 to 574 ft).

The tunnel which houses the collider is 3.8-meters (12 ft) wide, and was previously used to house the Large Electron-Positron Collider (which operated between 1989 and 2000). This tunnel contains two adjacent parallel beamlines that intersect at four points, each containing a beam that travels in opposite directions around the ring. The beam is controlled by 1,232 dipole magnets while 392 quadrupole magnets are used to keep the beams focused.

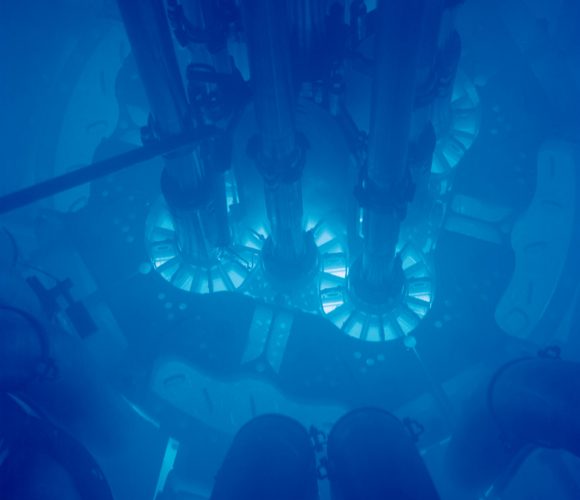

About 10,000 superconducting magnets are used in total, which are kept at an operational temperature of -271.25 °C (-456.25 °F) – which is just shy of absolute zero – by approximately 96 tonnes of liquid helium-4. This also makes the LHC the largest cryogenic facility in the world.

When conducting proton collisions, the process begins with the linear particle accelerator (LINAC 2). After the LINAC 2 increases the energy of the protons, these particles are then injected into the Proton Synchrotron Booster (PSB), which accelerates them to high speeds.

They are then injected into the Proton Synchrotron (PS), and then onto the Super Proton Synchrtron (SPS), where they are sped up even further before being injected into the main accelerator. Once there, the proton bunches are accumulated and accelerated to their peak energy over a period of 20 minutes. Last, they are circulated for a period of 5 to 24 hours, during which time collisions occur at the four intersection points.

During shorter running periods, heavy-ion collisions (typically lead ions) are included the program. The lead ions are first accelerated by the linear accelerator LINAC 3, and the Low Energy Ion Ring (LEIR) is used as an ion storage and cooler unit. The ions are then further accelerated by the PS and SPS before being injected into LHC ring.

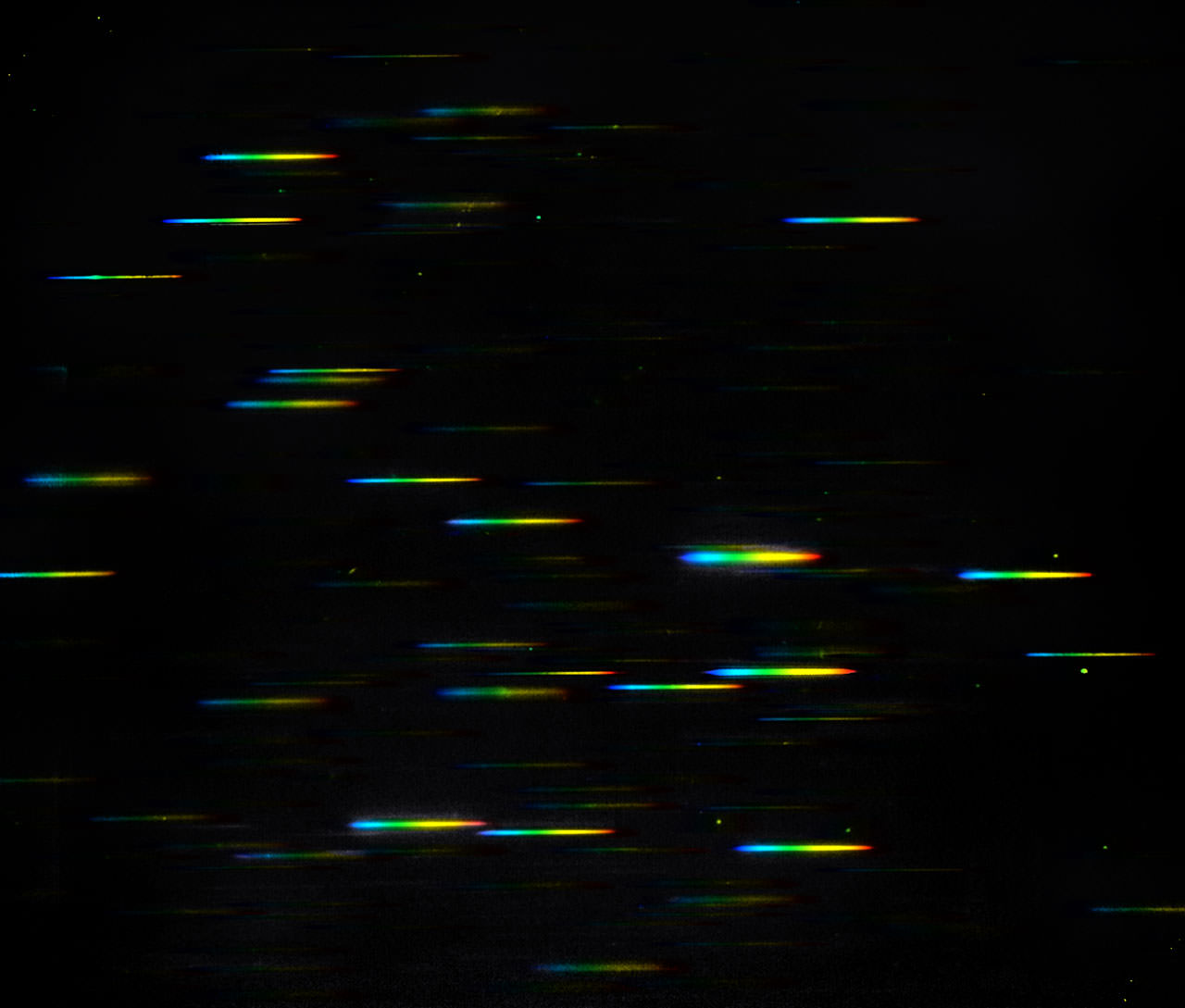

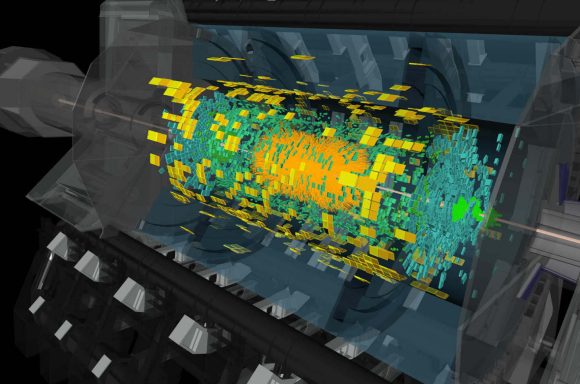

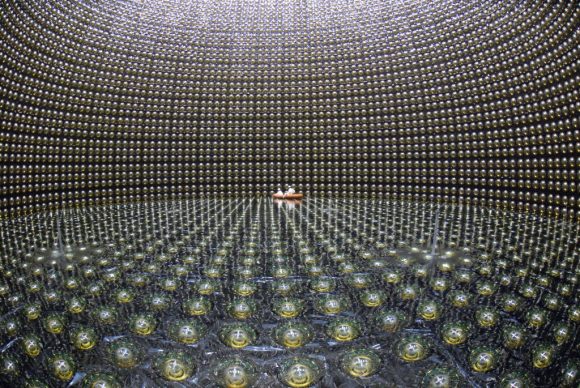

While protons and lead ions are being collided, seven detectors are used to scan for their byproducts. These include the A Toroidal LHC ApparatuS (ATLAS) experiment and the Compact Muon Solenoid (CMS), which are both general purpose detectors designed to see many different types of subatomic particles.

Then there are the more specific A Large Ion Collider Experiment (ALICE) and Large Hadron Collider beauty (LHCb) detectors. Whereas ALICE is a heavy-ion detector that studies strongly-interacting matter at extreme energy densities, the LHCb records the decay of particles and attempts to filter b and anti-b quarks from the products of their decay.

Then there are the three small and highly-specialized detectors – the TOTal Elastic and diffractive cross section Measurement (TOTEM) experiment, which measures total cross section, elastic scattering, and diffractive processes; the Monopole & Exotics Detector (MoEDAL), which searches magnetic monopoles or massive (pseudo-)stable charged particles; and the Large Hadron Collider forward (LHCf) that monitor for astroparticles (aka. cosmic rays).

History of Operation:

CERN, which stands for Conseil Européen pour la Recherche Nucléaire (or European Council for Nuclear Research in English) was established on Sept 29th, 1954, by twelve western European signatory nations. The council’s main purpose was to oversee the creation of a particle physics laboratory in Geneva where nuclear studies would be conducted.

Soon after its creation, the laboratory went beyond this and began conducting high-energy physics research as well. It has also grown to include twenty European member states: France, Switzerland, Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Finland, Spain, Portugal, Greece, Italy, the UK, Poland, Hungary, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Bulgaria and Israel.

Construction of the LHC was approved in 1995 and was initially intended to be completed by 2005. However, cost overruns, budget cuts, and various engineering difficulties pushed the completion date to April of 2007. The LHC first went online on September 10th, 2008, but initial testing was delayed for 14 months following an accident that caused extensive damage to many of the collider’s key components (such as the superconducting magnets).

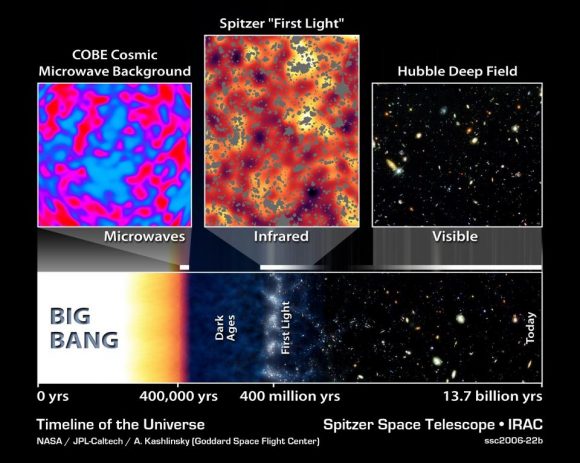

On November 20th, 2009, the LHC was brought back online and its First Run ran from 2010 to 2013. During this run, it collided two opposing particle beams of protons and lead nuclei at energies of 4 teraelectronvolts (4 TeV) and 2.76 TeV per nucleon, respectively. The main purpose of the LHC is to recreate conditions just after the Big Bang when collisions between high-energy particles was taking place.

Major Discoveries:

During its First Run, the LHCs discoveries included a particle thought to be the long sought-after Higgs Boson, which was announced on July 4th, 2012. This particle, which gives other particles mass, is a key part of the Standard Model of physics. Due to its high mass and elusive nature, the existence of this particle was based solely in theory and had never been previously observed.

The discovery of the Higgs Boson and the ongoing operation of the LHC has also allowed researchers to investigate physics beyond the Standard Model. This has included tests concerning supersymmetry theory. The results show that certain types of particle decay are less common than some forms of supersymmetry predict, but could still match the predictions of other versions of supersymmetry theory.

In May of 2011, it was reported that quark–gluon plasma (theoretically, the densest matter besides black holes) had been created in the LHC. On November 19th, 2014, the LHCb experiment announced the discovery of two new heavy subatomic particles, both of which were baryons composed of one bottom, one down, and one strange quark. The LHCb collaboration also observed multiple exotic hadrons during the first run, possibly pentaquarks or tetraquarks.

Since 2015, the LHC has been conducting its Second Run. In that time, it has been dedicated to confirming the detection of the Higgs Boson, and making further investigations into supersymmetry theory and the existence of exotic particles at higher-energy levels.

In the coming years, the LHC is scheduled for a series of upgrades to ensure that it does not suffer from diminished returns. In 2017-18, the LHC is scheduled to undergo an upgrade that will increase its collision energy to 14 TeV. In addition, after 2022, the ATLAS detector is to receive an upgrade designed to increase the likelihood of it detecting rare processes, known as the High Luminosity LHC.

The collaborative research effort known as the LHC Accelerator Research Program (LARP) is currently conducting research into how to upgrade the LHC further. Foremost among these are increases in the beam current and the modification of the two high-luminosity interaction regions, and the ATLAS and CMS detectors.

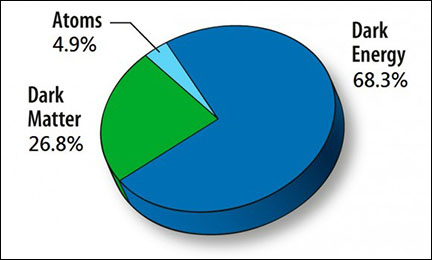

Who knows what the LHC will discover between now and the day when they finally turn the power off? With luck, it will shed more light on the deeper mysteries of the Universe, which could include the deep structure of space and time, the intersection of quantum mechanics and general relativity, the relationship between matter and antimatter, and the existence of “Dark Matter”.

We have written many articles about CERN and the LHC for Universe Today. Here’s What is the Higgs Boson?, The Hype Machine Deflates After CERN Data Shows No New Particle, BICEP2 All Over Again? Researchers Place Higgs Boson Discovery in Doubt, Two New Subatomic Particles Found, Is a New Particle about to be Announced?, Physicists Maybe, Just Maybe, Confirm the Possible Discovery of 5th Force of Nature.

If you’d like more info on the Large Hadron Collider, check out the LHC Homepage, and here’s a link to the CERN website.

Astronomy Cast also has some episodes on the subject. Listen here, Episode 69: The Large Hadron Collider and The Search for the Higgs Boson and Episode 392: The Standard Model – Intro.

Sources:

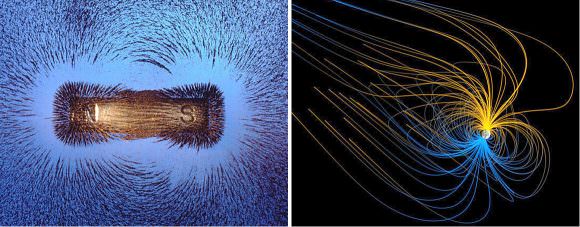

![Computer simulation of the Earth's field in a period of normal polarity between reversals.[1] The lines represent magnetic field lines, blue when the field points towards the center and yellow when away. The rotation axis of the Earth is centered and vertical. The dense clusters of lines are within the Earth's core](https://www.universetoday.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/03/Geodynamo_Between_Reversals-e1449100829326-580x442.gif)