This week, millions of people will turn their eyes to the skies in anticipation of the 2015 Perseid meteor shower. But what happens on less eventful nights, when we find ourselves gazing upward simply to admire the deep, dark, star-spangled sky? Far away from the glow of civilization, we humans can survey thousands of tiny pinpricks of light. But how? Where does that light come from? How does it make its way to us? And how do our brains sort all that incoming energy into such a profoundly breathtaking sight?

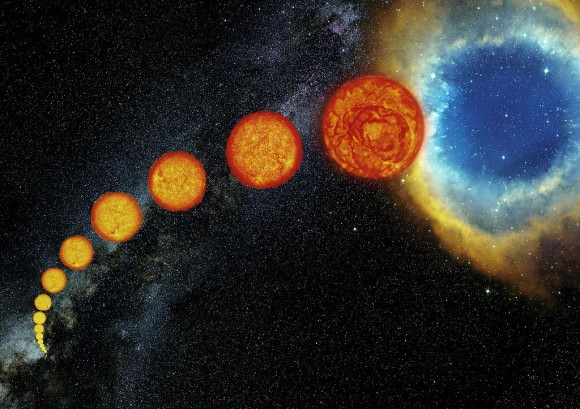

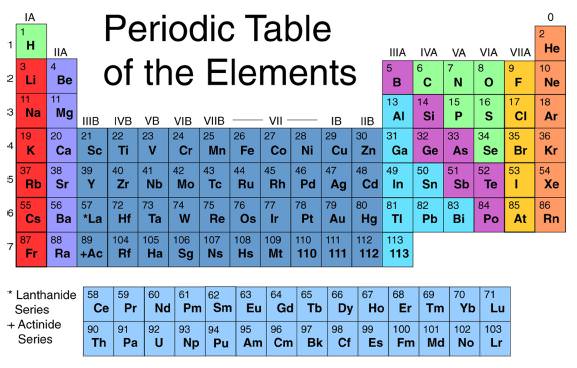

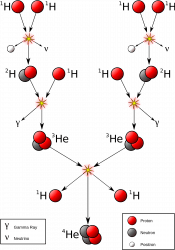

Our story begins lightyears away, deep in the heart of a sun-like star, where gravity’s immense inward pressure keeps temperatures high and atoms disassembled. Free protons hurtle around the core, occasionally attaining the blistering energies necessary to overcome their electromagnetic repulsion, collide, and stick together in pairs of two.

So-called diprotons are unstable and tend to disband as quickly as they arise. And if it weren’t for the subatomic antics of the weak nuclear force, this would be the end of the line: no fusion, no starlight, no us. However, on very rare occasions, a process called beta decay transforms one proton in the pair into a neutron. This new partnership forms what is known as deuterium, or heavy hydrogen, and opens the door to further nuclear fusion reactions.

Indeed, once deuterium enters the mix, particle pileups happen far more frequently. A free proton slams into deuterium, creating helium-3. Additional impacts build upon one another to forge helium-4 and heavier elements like oxygen and carbon.

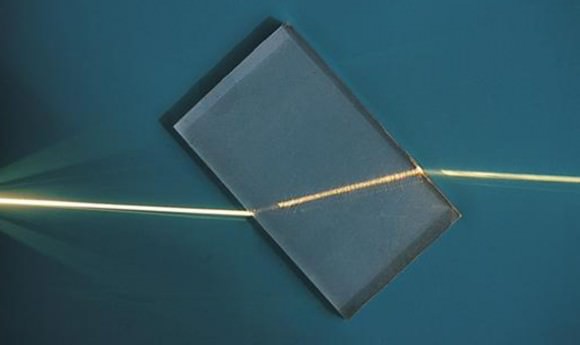

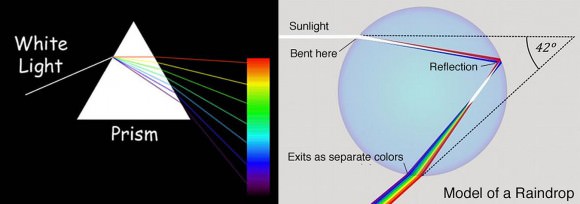

Such collisions do more than just build up more massive atoms; in fact, every impact listed above releases an enormous amount of energy in the form of gamma rays. These high-energy photons streak outward, providing thermonuclear pressure that counterbalances the star’s gravity. Tens or even hundreds of thousands of years later, battered, bruised, and energetically squelched from fighting their way through a sun-sized blizzard of other particles, they emerge from the star’s surface as visible, ultraviolet, and infrared light.

Ta-da!

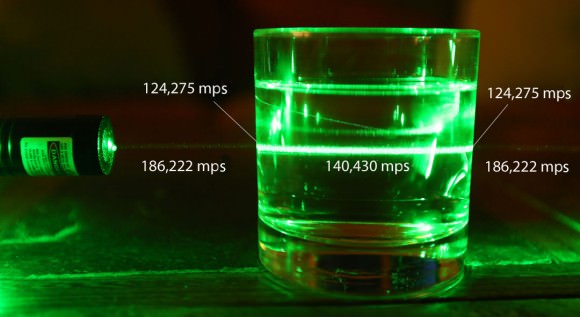

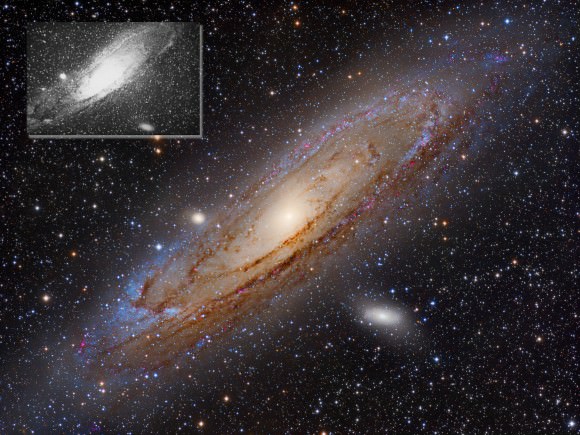

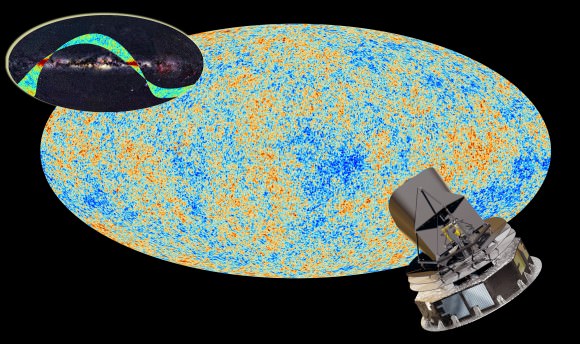

But this is only half the story. The light then has to stream across vast reaches of space in order to reach the Earth – a process that, provided the star of origin is in our own galaxy, can take anywhere from 4.2 years to many thousands of years! At least… from your perspective. Since photons are massless, they don’t experience any time at all! And even after eluding what, for any other massive entity in the Universe, would be downright interminable flight times, conditions still must align so that you can see even one twinkle of the light from a faraway star.

That is, it must be dark, and you must be looking up.

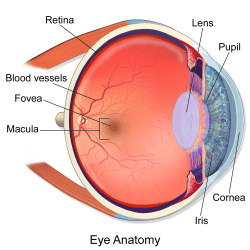

The incoming stream of photons then makes its way through your cornea and lens and onto your retina, a highly vascular layer of tissue that lines the back of the eye. There, each tiny packet of light impinges upon one of two types of photoreceptor cell: a rod, or a cone.

Most photons detected under the low-light conditions of stargazing will activate rod cells. These cells are so light-sensitive that, in dark enough conditions, they can be excited by a single photon! Rods cannot detect color, but are far more abundant than cones and are found all across the retina, including around the periphery.

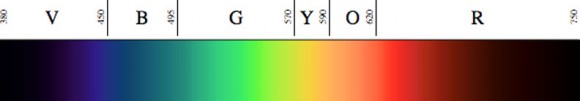

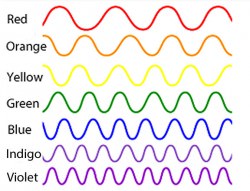

The less numerous, more color-hungry cone cells are densely concentrated at the center of the retina, in a region called the fovea (this explains why dim stars that are visible in your side vision suddenly seem to disappear when you attempt to look at them straight-on). Despite their relative insensitivity, cone cells can be activated by very bright starlight, enabling you to perceive stars like Vega as blue and Betelgeuse as red.

But whether bright light or dim, every photon has the same endpoint once it reaches one of your eyes’ photoreceptors: a molecule of vitamin A, which is bound together with a specialized protein called an opsin. Vitamin A absorbs the light and triggers a signal cascade: ion channels open and charged particles rush across a membrane, generating an electrical impulse that travels up the optic nerve and into the brain. By the time this signal reaches your brain’s visual cortex, various neural pathways are already hard at work translating this complex biochemistry into what you once thought was a simple, intuitive, and poetic understanding of the heavens above…

The stars, they shine.

So the next time you go outside in the darker hours, take a moment to appreciate the great lengths it takes for just a single twinkle of light to travel from a series of nuclear reactions in the bustling center of a distant star, across the vastness of space and time, through your body’s electrochemical pathways, and into your conscious mind.

It gives every last one of those corny love songs new meaning, doesn’t it?