[/caption]

In 1988, John Cardy asked if there was a c-theorem in four dimensions. At the time, he reasonably expected his work on theories of quantum particles and fields to be professionally put to the test… But it never happened. Now – a quarter of a century later – it seems he was right.

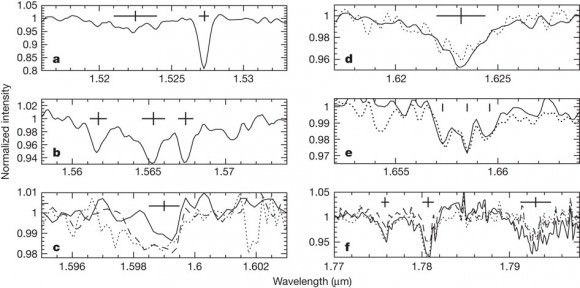

“It is shown that, for d even, the one-point function of the trace of the stress tensor on the sphere, Sd, when suitably regularized, defines a c-function, which, at least to one loop order, is decreasing along RG trajectories and is stationary at RG fixed points, where it is proportional to the usual conformal anomaly.” said Cardy. “It is shown that the existence of such a c-function, if it satisfies these properties to all orders, is consistent with the expected behavior of QCD in four dimensions.”

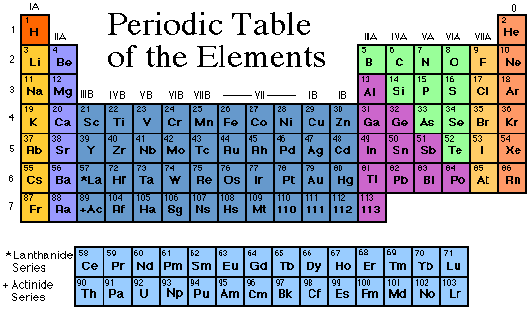

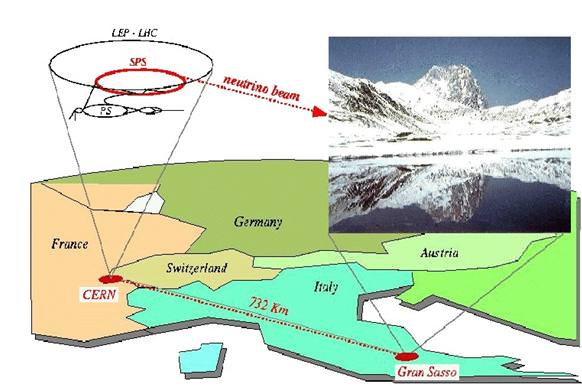

His speculation is the a-theorem… a multitude of avenues in which quantum fields can be energetically excited (a) is always greater at high energies than at low energies. If this theory is correct, then it likely will explain physics beyond the current model and shed light on any possible unknown particles yet to be revealed by the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN, Europe’s particle physics lab near Geneva, Switzerland.

“I’m pleased if the proof turns out to be correct,” says Cardy, a theoretical physicist at the University of Oxford, UK. “I’m quite amazed the conjecture I made in 1988 stood up.”

According to theorists Zohar Komargodski and Adam Schwimmer of the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel, the proof of Cardy’s theories was presented July 2011, and is slowly gaining notoriety among the scientific community as other theoretical physicists take note of his work.

“I think it’s quite likely to be right,” says Nathan Seiberg, a theoretical physicist at the Institute of Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey.

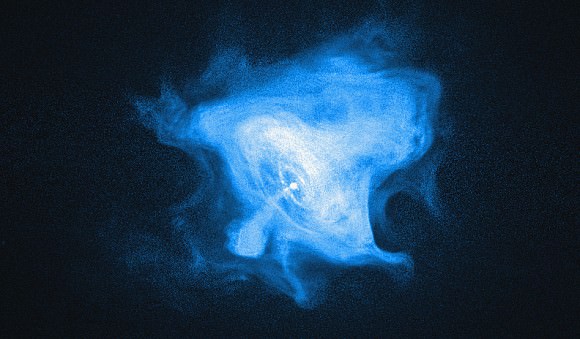

The field of quantum theory always stands on shaky ground… it seems that no one can be 100% accurate on their guesses of how particles should behave. According to the Nature news release, one example is quantum chromodynamics — the theory of the strong nuclear force that describes the interactions between quarks and gluons. That lack leaves physicists struggling to relate physics at the high-energy, short-distance scale of quarks to the physics at longer-distance, lower-energy scales, such as that of protons and neutrons.

“Although lots of work has gone into relating short- and long-distance scales for particular quantum field theories, there are relatively few general principles that do this for all theories that can exist,” says Robert Myers, a theoretical physicist at the Perimeter Institute in Waterloo, Canada.

However, Cardy’s a-theorem just might be the answer – in four dimensions – the three dimensions of space and the dimension of time. However, in 2008, two physicists found a counter-example of a quantum field theory that didn’t obey the rule. But don’t stop there. Two years later Seiberg and his colleagues re-evaluated the counter-example and discovered errors. These findings led to more studies of Cardy’s work and allowed Schwimmer and Komargodski to state their conjecture. Again, it’s not perfect and some areas need further clarification. But Myers thinks that the proof is correct. “If this is a complete proof then this becomes a very powerful principle,” he says. “If it isn’t, it’s still a general idea that holds most of the time.”

According to Nature, Ken Intriligator, a theoretical physicist at the University of California, San Diego, agrees, adding that whereas mathematicians require proofs to be watertight, physicists tend to be satisfied by proofs that seem mostly right, and intrigued by any avenues to be pursued in more depth. Writing on his blog on November 9, Matt Strassler, a theoretical physicist at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, New Jersey, described the proof as “striking” because the whole argument follows once one elegant technical idea has been established.

With Cardy’s theory more thoroughly tested, chances are it will be applied more universally in the areas of quantum field theories. This may unify physics, including the area of supersymmetry and aid the findings with the LHC. The a-theorem “will be a guiding tool for theorists trying to understand the physics”, predicts Myers.

Pehaps Cardy’s work will even expand into condensed matter physics, an area where quantum field theories are used to elucidate on new states of materials. The only problem is the a-theorem has only had proof in two and four dimensions – where a few areas of condensed matter physics embrace layers containing just three dimensions – two in space and one in time. However, Myers states that they’ll continue to work on a version of the theorem in odd numbers of dimensions. “I’m just hoping it won’t take another 20 years,” he says.

Original Story Source: Nature News Release. For Further Reading: On Renormalization Group Flows in Four Dimensions.