[/caption]

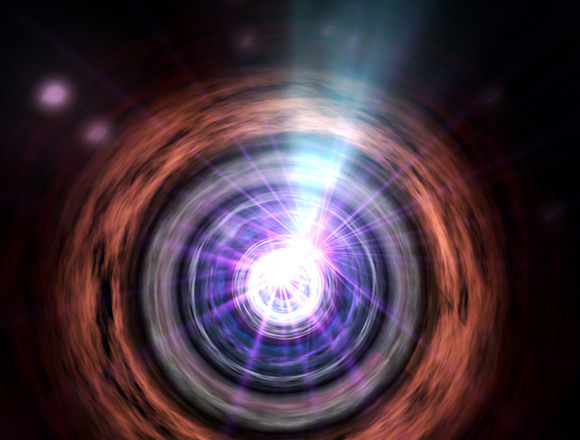

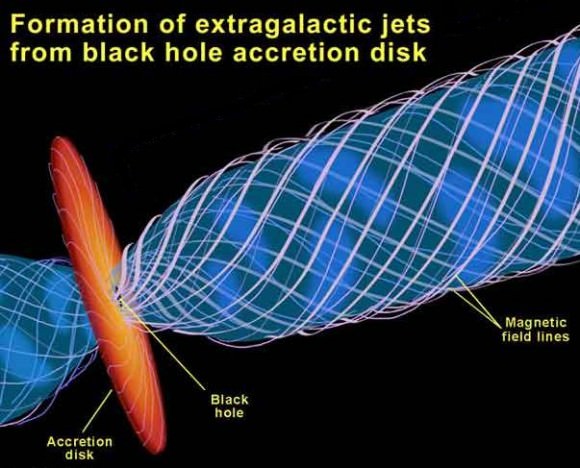

Polar jets are often found around objects with spinning accretion disks – anything from newly forming stars to ageing neutron stars. And some of the most powerful polar jets arise from accretion disks around black holes, be they of stellar or supermassive size. In the latter case, jets emerging from active galaxies such as quasars, with their jets roughly orientated towards Earth, are called blazars.

The physics underlying the production of polar jets at any scale is not completely understood. It is likely that twisting magnetic lines of force, generated within a spinning accretion disk, channel plasma from the compressed centre of the accretion disk into the narrow jets we observe. But exactly what energy transfer process gives the jet material the escape velocity required to be thrown clear is still subject to debate.

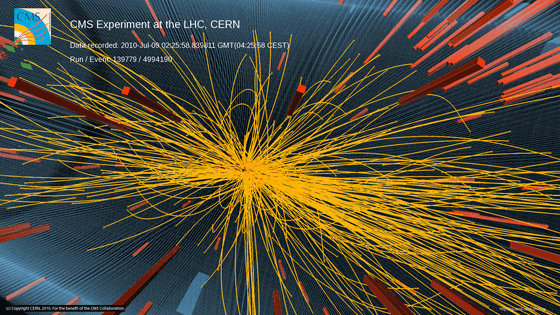

In the extreme cases of black hole accretion disks, jet material acquires escape velocities close to the speed of light – which is needed if the material is to escape from the vicinity of a black hole. Polar jets thrown out at such speeds are usually called relativistic jets.

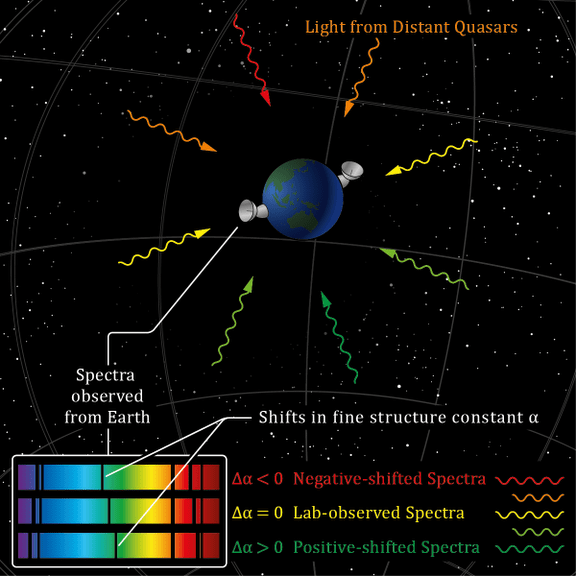

Relativistic jets from blazars broadcast energetically across the electromagnetic spectrum – where ground based radio telescopes can pick up their low frequency radiation, while space-based telescopes, like Fermi or Chandra, can pick up high frequency radiation. As you can see from the lead image of this story, Hubble can pick up optical light from one of M87‘s jets – although ground-based optical observations of a ‘curious straight ray’ from M87 were recorded as early as 1918.

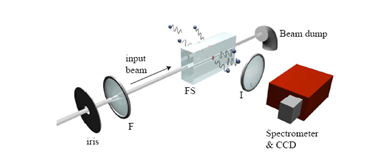

A recent review of high resolution data obtained from Very Long Baseline Interferometry (VLBI) – involving integrating data inputs from geographically distant radio telescope dishes into a giant virtual telescope array – is providing a bit more insight (although only a bit) into the structure and dynamics of jets from active galaxies.

The radiation from such jets is largely non-thermal (i.e. not a direct result of the temperature of the jet material). Radio emission probably results from synchrotron effects – where electrons spun rapidly within a magnetic field emit radiation across the whole electromagnetic spectrum, but generally with a peak in radio wavelengths. The inverse Compton effect, where a photon collision with a rapidly moving particle imparts more energy and hence a higher frequency to that photon, may also contribute to the higher frequency radiation.

Anyhow, VLBI observations suggest that blazar jets form within a distance of between 10 or 100 times the radius of the supermassive black hole – and whatever forces work to accelerate them to relativistic velocities may only operate over the distance of 1000 times that radius. The jets may then beam out over light year distances, as a result of that initial momentum push.

Shock fronts can be found near the base of the jets, which may represent points at which magnetically driven flow (Poynting flux) fades to kinetic mass flow – although magnetohydrodynamic forces continue operating to keep the jet collimated (i.e. contained within a narrow beam) over light year distances.

That was about as much as I managed to glean from this interesting, though at times jargon-dense, paper.

Further reading: Lobanov, A. Physical properties of blazar jets from VLBI observations.