[/caption]

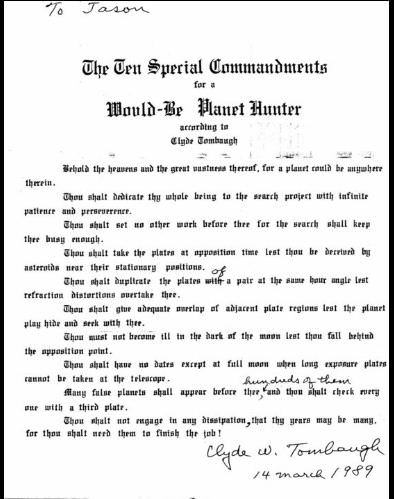

Back in 1989, amateur astronomer Toney Burkhart found out that Clyde Tombaugh was going to be giving a talk in San Francisco, just a short distance from Burkhart’s home. Trouble was, he found out only about 10 minutes before the presentation was going to start, so he rushed over and arrived just in time to hear Tombaugh’s talk, where he told amusing stories of how he found Pluto, and what he went through with night after night in a cold observatory taking photographs and comparing the glass plates, looking for a planet in the outer solar system. Then Tombaugh shared read his version of the Ten Commandments, called, “Ten Special Commandments for a Would-Be Planet Hunter.”

Afterward, the posters of the Commandments were being sold as a fund raising event.

“Clyde was going around the country to raise money for scholarships for young people to study planetary science,” Burkhart told Universe Today. “There were a lot of people there in the lobby buying posters autographed by Clyde Tombaugh and I wanted one very much.”

However, when Burkhart went to purchase one, he discovered that in his haste to leave his home, he had forgotten his billfold.

“I waited until everything was over and thought that I would at least go over and say hi to Clyde and tell him how much I thought of his hard work and to shake his hand, at least,” Burkhart said, and Tombaugh was more than happy to chat with an fellow astronomy enthusiast.

“While I was chatting with Clyde, I told him that I wish I brought money to buy one of the posters. He looked at me and smiled and said, ‘Well, that’s alright.’” And I said no, I really would have bought one if I had not ran out of the house and forgot my billfold. He was holding his notes and I asked him, what are you going to do with those notes, throw them away?”

Burkhart said Tombaugh smiled and replied that he couldn’t give away his notes, as he had more talks to give, but said he could mail them to Burkhart after his tour was over.

Burkhart offered to send Tombaugh a check later, or at least pay for postage, but Tombaugh looked at him and said, “No, that’s OK, I see you are really into astronomy and it would be my pleasure to give it you.”

Grateful, Burkhart asked if Tombaugh could autograph it, not for Burkhart but for his son Jason. Tombaugh took Burkhart’s address, and true to his word, about a month later Burkhart received Tombaugh’s personal version of the Commandments, with corrections made in pen, (the corrections were made by Tombaugh’s wife, Patricia, Burkhart said) along with his autograph. “I have them in safekeeping to leave to my son to have and hopefully give them to his kids,” Burkhart said.

Here are the the Ten Special Commandments for a Would-Be Planet Hunter, according to Clyde Tombaugh

1. Behold the heavens and the great vastness thereof, for a planet could be anywhere therein.

2. Thou shalt dedicate thy whole being to the search project with infinite patience and perseverance.

3. Though shalt set no other work before thee for the search shall keep thee busy enough.

4. Though shalt take the plates at opposition time lest thou be deceived by asteroids near their stationary positions.

5. Though shalt duplicate the plate of a pair at the same hour angle lest refraction distortions overtake thee.

6. Thou shalt give adequate overlap of adjacent plate regions lest the planet play hide and seek with thee.

7. Thou must not become ill in the dark of the moon lest thou fall behind the opposition point.

8. Thou shalt have no dates except at full moon when long exposure plates cannot be taken at the telescope.

9. Many false planets shall appear before thee, hundreds of them, and thou shalt check every one with a third plate.

10. Thou shalt not engage in any dissipation, that thy years may be many for thou shalt need them to finish the job!

Clyde W. Tombaugh

14 March 1989

Burkhart shared the scan of Tombaugh’s notes on his Facebook page.

h/t to Charles Bell.