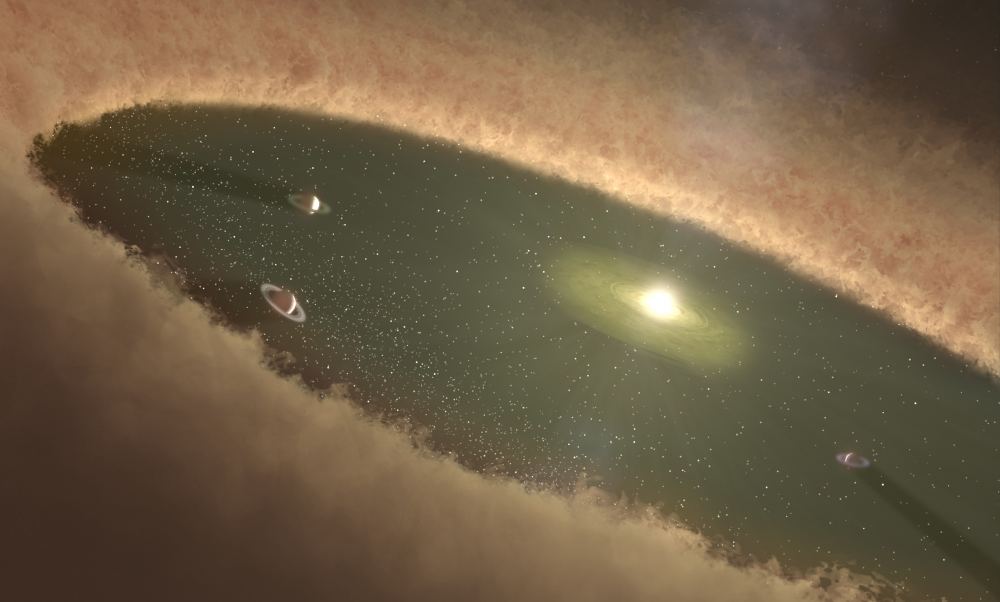

A fascinating set of finds was announced today at the 225th meeting of the American Astronomical Society (AAS), currently underway this week in Seattle, Washington. A team of astronomers announced the discovery of eight new planets potentially orbiting their host stars in their respective habitable zones. Also dubbed the ‘Goldilocks Zone,’ this is the distance where — like the tempting fairytale porridge — it’s not too hot, and not too cold, but juuusst right for liquid water to exist.

And chasing the water is the name of the game when it comes to hunting for life on other worlds. Two of the discoveries announced, Kepler-438b and Kepler-442b, are especially intriguing, as they are the most comparable to the Earth size-wise of any exoplanets yet discovered.

“Most of these planets have a good chance of being rocky, like Earth,” said Guillermo Torres in a recent press release. Guillermo is the lead author in the study for the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA).

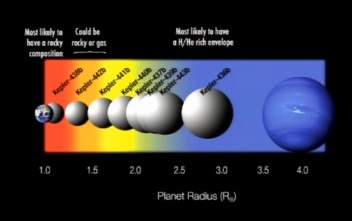

This also doubles the count of suspected terrestrial exo-worlds — planets with less than twice the diameter of the Earth — inferred to orbit in the habitable zone of their host stars.

Fans on exoplanet science will remember the announcement of the first prospective Earth-like world orbiting in the habitable zone of its host star, Kepler-186f announced just last year.

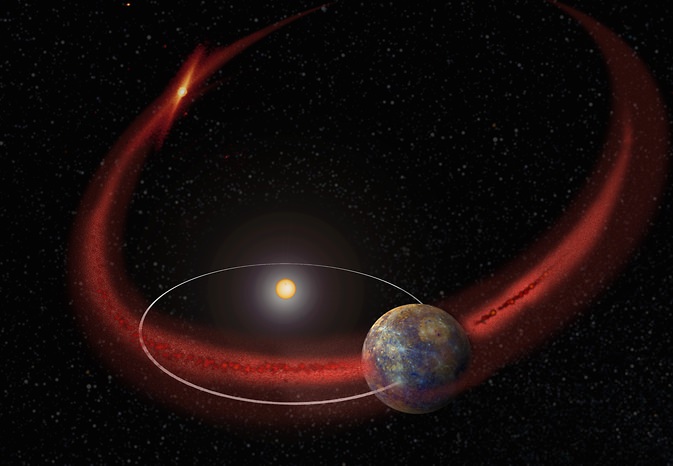

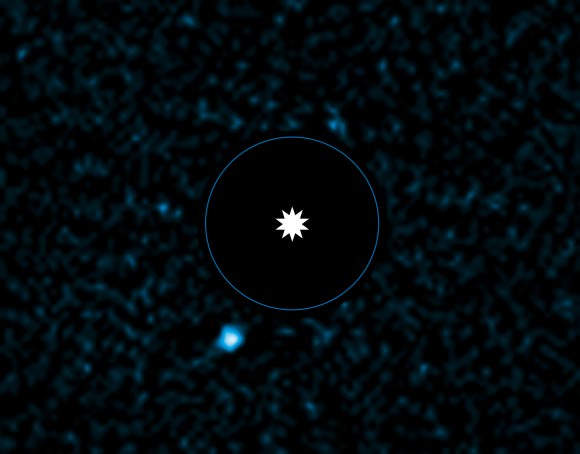

The Kepler Space Telescope looks for planets used a technique known as the transit method. If a planet is orbiting its host star along our line of sight, a small but measurable dip in the star’s brightness occurs. This has advantages over the radial velocity technique because it allows researchers to pin down the hidden planet’s orbit and size much more precisely. The transit method is biased, however, to planets close in to its host which happen to lie along our solar system-bound line of sight. Kepler may miss most exo-worlds inclined out of its view, but it overcomes this by staring at thousands of stars.

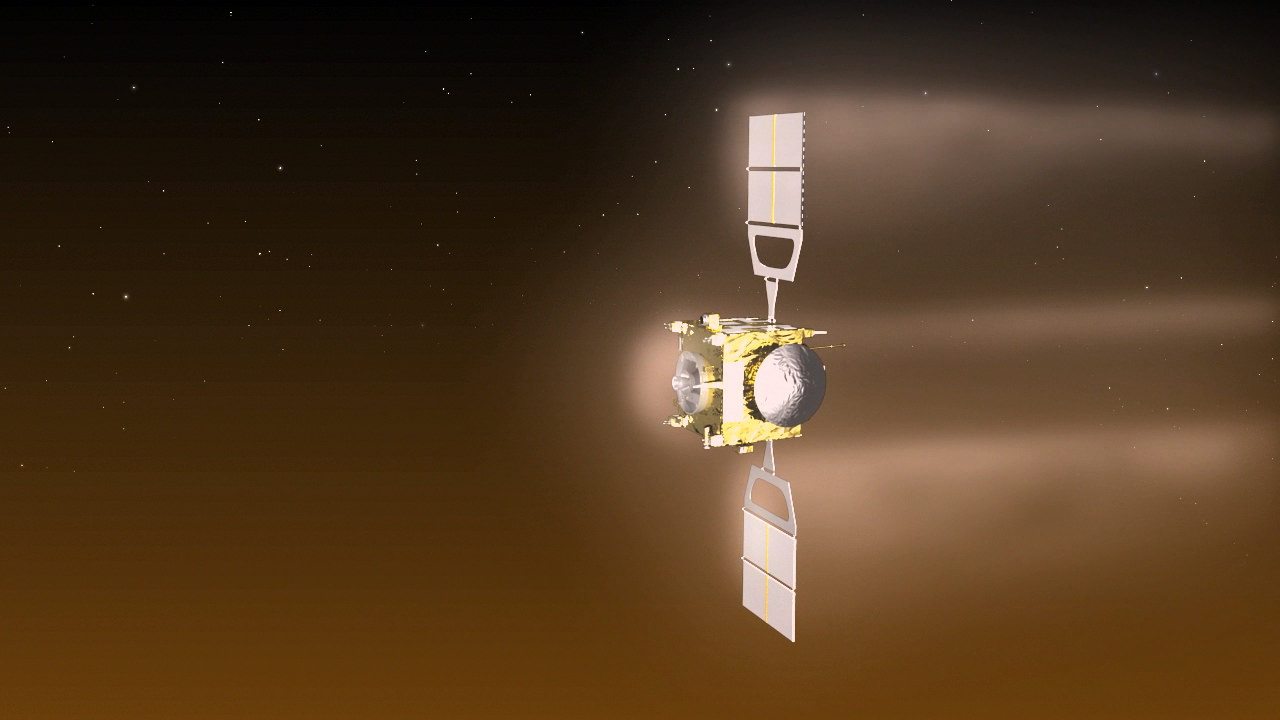

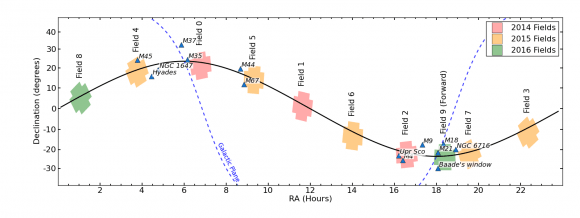

Launched in 2009, Kepler has wrapped up its primary phase of starring at a patch of sky along the plane of the Milky Way in the directions of the constellations of Cygnus, Lyra and Hercules, and is now in its extended K2 mission using the solar wind pressure as a 3rd ‘reaction wheel’ to carry out targeted searches along the ecliptic plane.

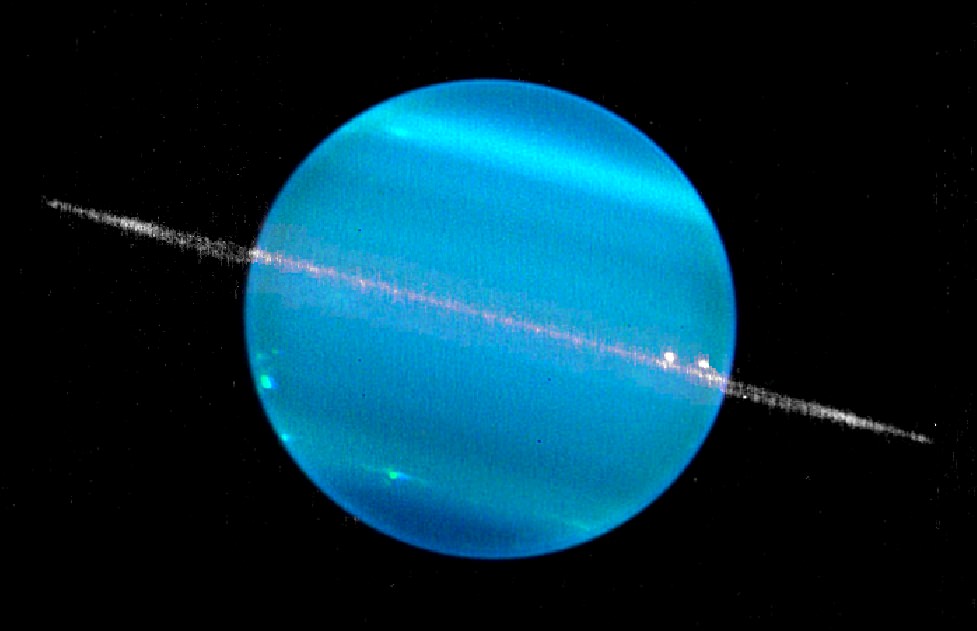

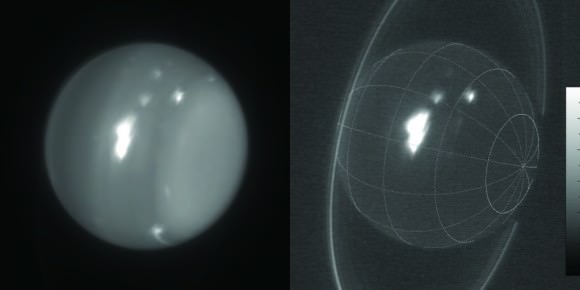

Both newly discovered worlds highlighted in today’s announcement orbit distant red dwarf stars. Kepler-438 b is estimated to be 12% larger in diameter than the Earth, and Kepler-442 b is estimated by the team to be 33% larger. These worlds have a 70% and 60% chance of being rocky, respectively. For comparison, Ice giant planet Uranus is 4 times the diameter of the Earth, and over 14 times more massive.

“We don’t know for sure whether any of the planets in our sample are truly habitable,” Said CfA co-researcher in the study David Kipping. All we can say is that they’re promising candidates.”

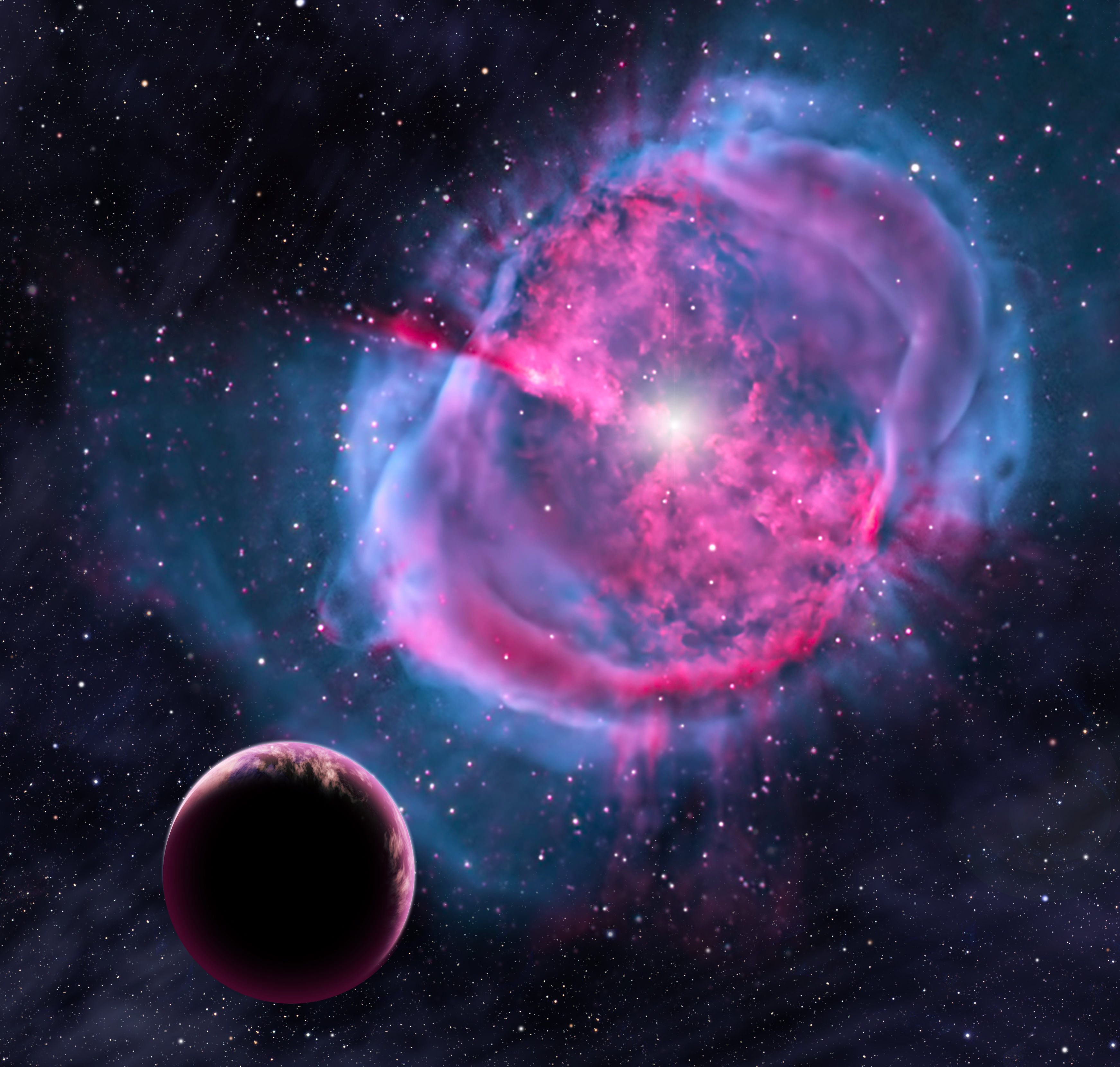

The idea of habitable worlds around red dwarf stars is a tantalizing one. These stars are fainter and cooler than our Sun, and 7.5% to 50% as massive. They also have two primary factors going for them: they’re the most common type of stars in the universe, and they have life spans measured in trillions of years, much longer than the current age of the universe. If life could go from muck to making microwave dinners here on Earth in just a few billion years, it’s had lots longer to do the same on worlds orbiting red dwarf stars.

There is, however, one catch: the habitable zone surrounding a red dwarf is much closer in to its host star, and any would-be planet is subject to frequent surface-sterilizing flares. Perhaps a world with a synchronous rotation might be spared this fate and feature a habitable hemisphere well inside the snow line permanently turned away from its host.

The team made these discoveries by sifting though Kepler’s preliminary finds that are termed KOI’s, or Kepler Objects of Interest. Though these potential discoveries were far too small to pin down their masses using the traditional method, the team employed a program named BLENDER to statically validate the finds. BLENDER has been employed before in concert with backup observations for extremely tiny exoplanet discoveries. Torres and Francois Fressin developed the BLENDER program, and it is currently run on the massive Pleiades supercomputer at NASA Ames.

It was also noted in today’s press conference that two KOIs awaiting validation — 5737.01 and 2194.03 — may also prove to be terrestrial worlds orbiting Sun-like stars that are possibly similar in size to the Earth.

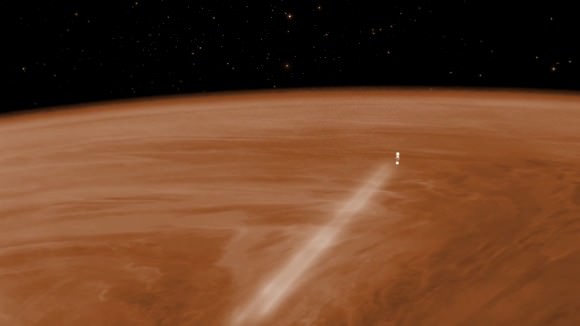

But don’t plan on building an interstellar ark and heading off to these newly found worlds just yet. Kepler-438b sits 470 light years from Earth, and Kepler-442b is even farther away at 1,100 light years. And we’ll also add our usual caveat and caution that, from a distance, the planet Venus in our own solar system might look like a tempting vacation spot. (Spoiler alert: it’s not).

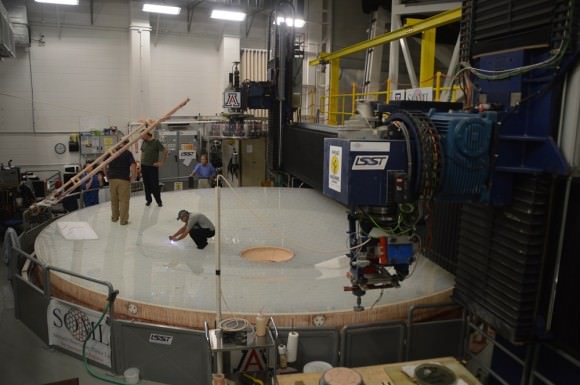

Still, these discoveries are fascinating finds and add to the growing menagerie of exoplanet systems. These will also serve as great follow up targets for TESS, Gaia and LSST survey, all set to add to our exoplanet knowledge in the coming decade.

And to think, I remember growing up as a child of the 1970s reading that exoplanet detections were soooo difficult that they might never occur in our lifetime… now, fast-forward to 2015, and we’re beginning to classify and characterize other brave new solar systems in the modern Age of Exoplanet Science.

-Looking to observe red dwarf stars with your backyard scope? Check out our handy list.