[/caption]

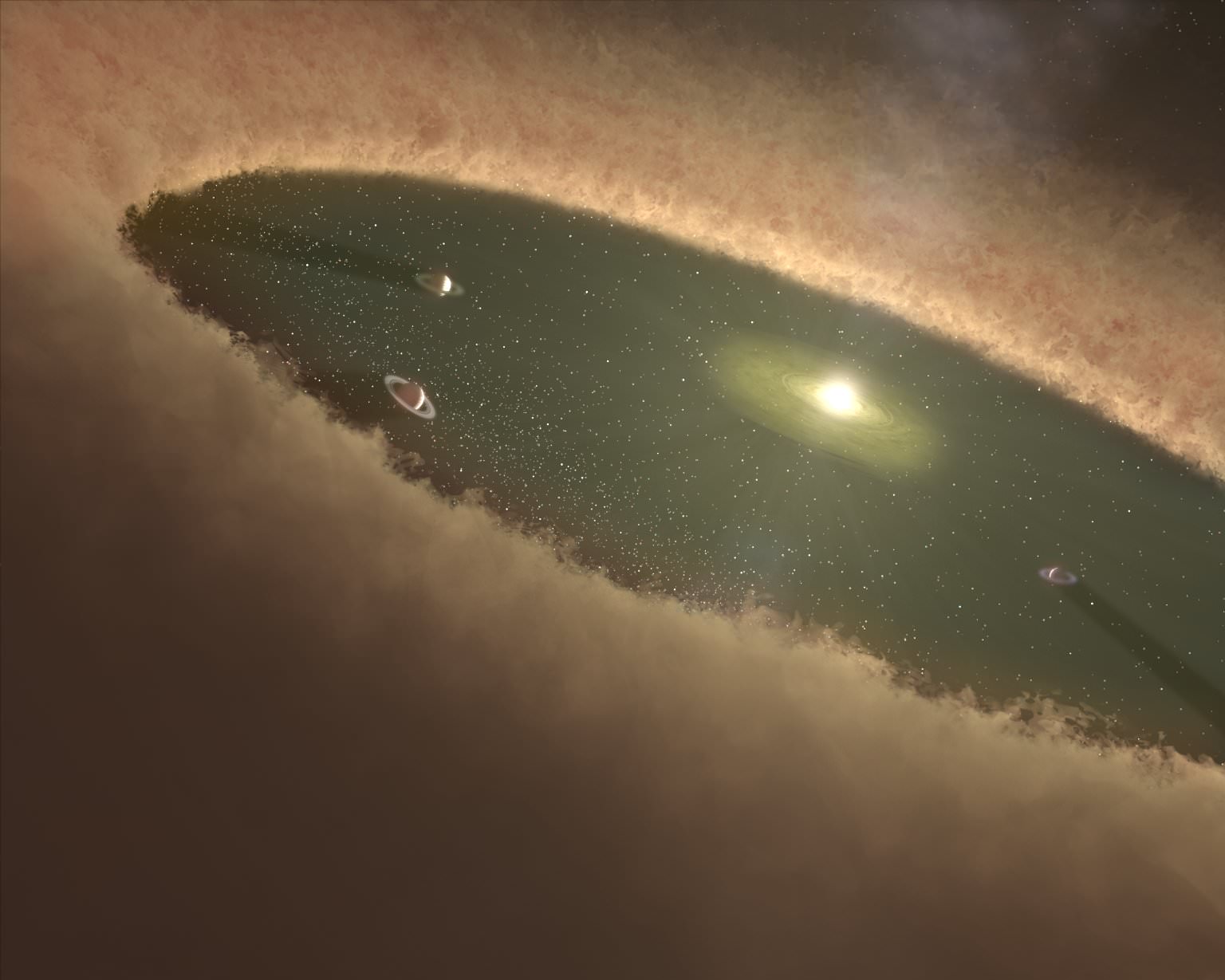

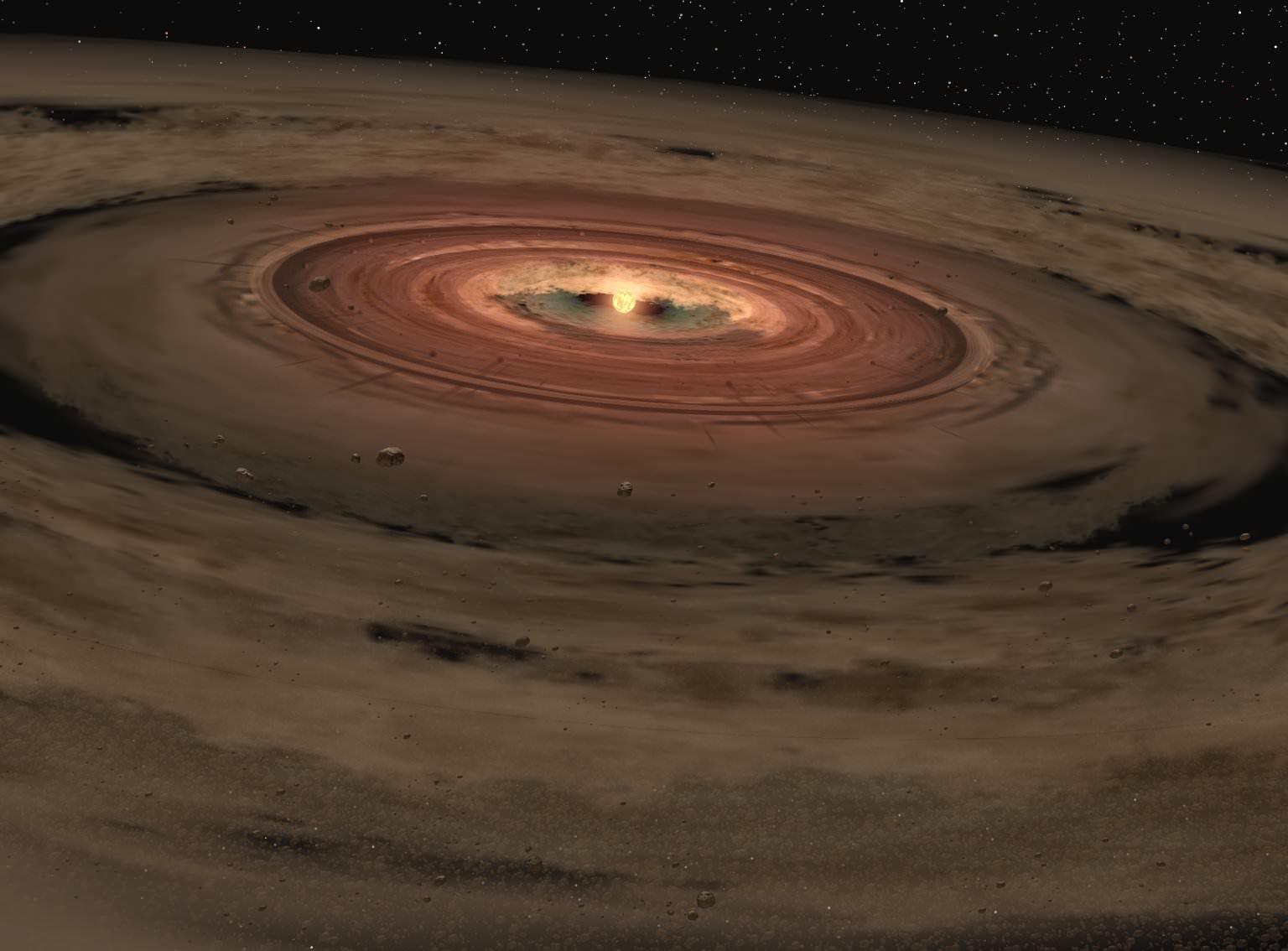

A Japanese team of astronomers have reported a strong correlation between the metallicity of dusty protoplanetary disks and their longevity. From this finding they propose that low metallicity stars are much less likely to have planets, including gas giants, due to the shorter lifetime of their protoplanetary disks.

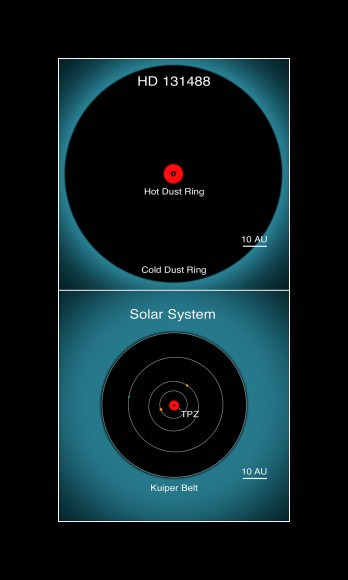

As you are probably aware, ‘metal’ is astronomy-speak for anything higher up the periodic table than hydrogen and helium. The Milky Way has a metallicity gradient – where metallicity drops markedly the further out you go. In the extreme outer galaxy, about 18 kiloparsecs out from the centre, the metallicity of stars is only 10% that of the Sun (which is about 8 kiloparsecs – or around 25,000 light years – out from the centre).

This study compared young star clusters within stellar nurseries with relatively high metallicity (like the Orion nebula) against more distant clusters in the outer galaxy within low metallicity nurseries (like Digel Cloud 2).

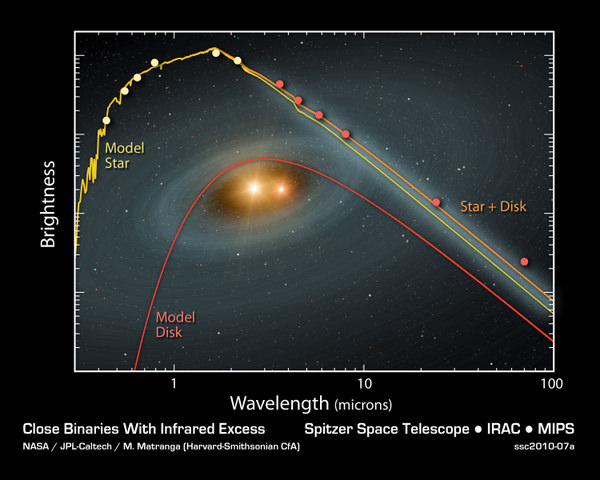

The study’s conclusions are based on the assumption that the radiation output of stars with dense protoplanetary disks will have an excess of near and mid-infra red wavelengths. This is largely because the star heats its surrounding protoplanetary disk, making the disk radiate in infra-red.

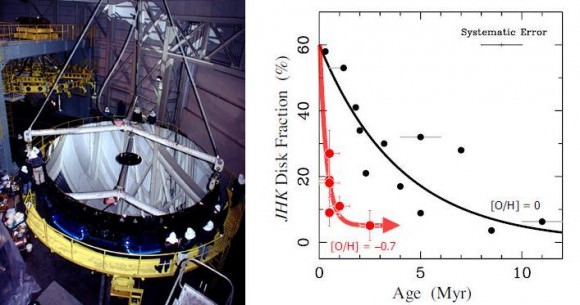

The research team used the 8.2 metre Subaru Telescope and a procedure called JHK photometry to identify a measure they called ‘disk fraction’, representing the density of the protoplanetary disk (as determined by the excess of infra red radiation). They also used another established mass-luminosity relation measure to determine the age of the clusters.

Graphing disk fraction over age for populations of Sun-equivalent metallicity stars versus populations of low metallicity stars in the outer galaxy suggests that the protoplanetary disks of those low metallicity stars disperse much quicker.

The authors suggest that the process of photoevaporation may underlie the shorter lifespan of low metal disks – where the impact of photons is sufficient to quickly disperse low atomic mass hydrogen and helium, while the presence of higher atomic weight metals may deflect those photons and hence sustain a protoplanetary disk over a longer period.

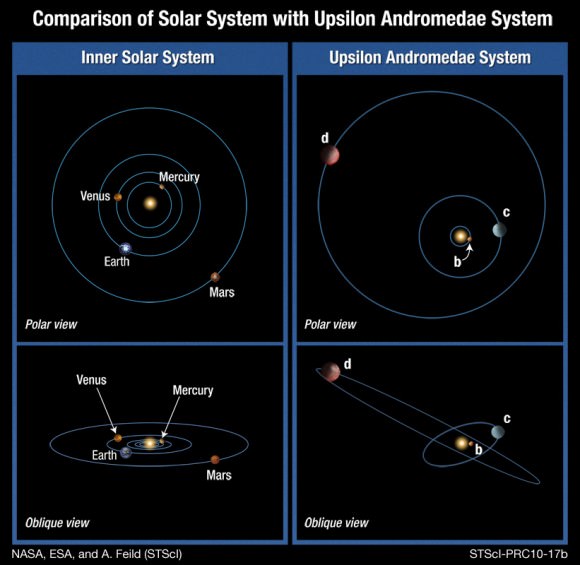

As the authors point out, the lower lifetime of low metallicity disks reduces the likelihood of planet formation. Although the authors steer clear of much more speculation, the implications of this relationship seem to be that, as well as expecting to find less planets around stars towards the outer edge of the galaxy – we might also expect to find less planets around any old Population II stars that would have also formed in environments of low metallicity.

Indeed, these findings suggest that planets, even gas giants, may have been exceedingly rare in the early universe – and have only become commonplace later in the universe’s evolution – after stellar nucleosynthesis processes had adequately seeded the cosmos with metals.

Further reading: Yasui, C., Kobayashi, N., Tokunaga, A., Saito, M. and Tokoku, C.

Short Lifetime of Protoplanetary Disks in Low-Metallicity Environments