So you’ve seen all of the classic naked eye planets. Maybe you’ve even seen fleet-footed Mercury as it reached greatest elongation earlier this month. And perhaps you’ve hunted down dim Uranus and Neptune with a telescope as they wandered about the stars…

But have you ever seen Pluto?

Regardless of whether or not you think it’s a planet, now is a good time to try. With this past weekend’s perigee Full Moon sliding out of the evening picture, we’re reaching that “dark of the Moon” two week plus stretch where it’s once again possible to go after faint targets.

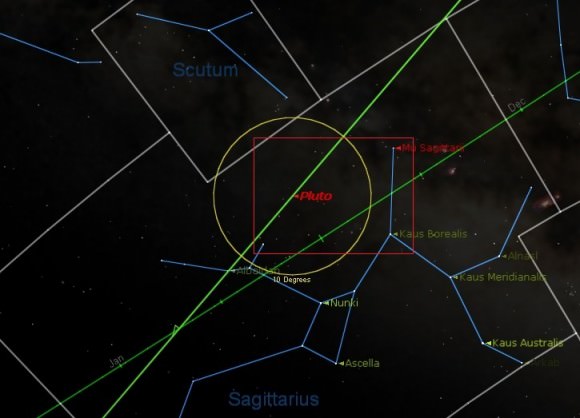

This year, Pluto reaches opposition on July 1st, 2013 in the constellation Sagittarius. This means that as the Sun sets, Pluto will be rising opposite to it in sky, and transit the meridian around local midnight.

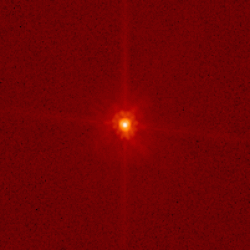

But finding it won’t be easy. Pluto currently shines at magnitude +14, 1,600 times fainter than what can be seen by the naked eye under favorable sky conditions. Compounding the situation is Pluto’s relatively low declination for northern hemisphere observers. You’ll need a telescope, good seeing, dark skies and patience to nab this challenging object.

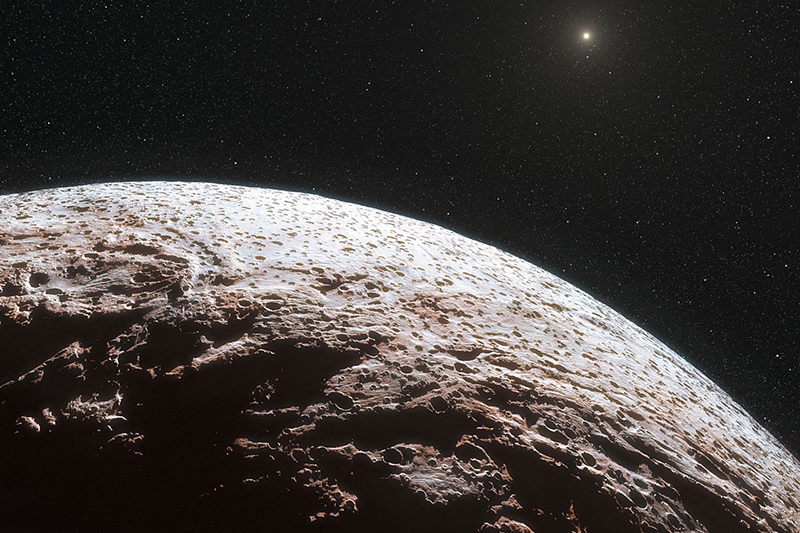

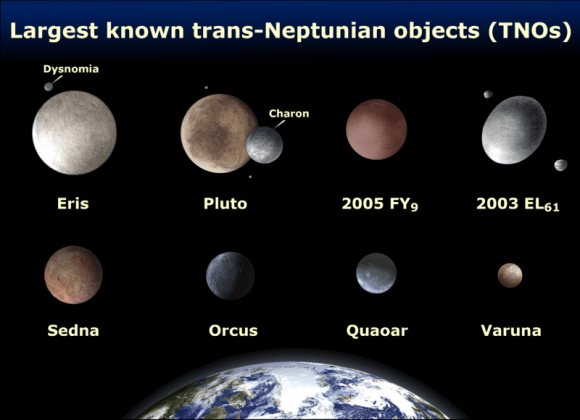

Don’t expect Pluto to look like much. Like asteroids and quasars, part of the thrill of spotting such a dim speck lies in knowing what you’re seeing. Currently located just over 31 Astronomical Units (AUs) distant, tiny Pluto takes over 246 years to orbit the Sun. In fact, it has yet to do so once since its discovery by Clyde Tombaugh from the Lowell observatory in 1930. Pluto was located in the constellation Gemini near the Eskimo nebula (NGC 2392) during its discovery.

And not all oppositions are created equal. Pluto has a relatively eccentric orbit, with a perihelion of 29.7 AUs and an aphelion of 48.9 AUs. It reached perihelion on September 5th, 1989 and is now beginning its long march back out of the solar system, reaching aphelion on February 19th, 2114.

Pluto last reached aphelion on June 4th, 1866, and won’t approach perihelion again until the far off date of September 15th, 2237.

This means that Pluto is getting fainter as seen from Earth on each successive opposition. Pluto reaches magnitude +13.7 when opposition occurs near perihelion, and fades to +15.9 (over 6 times fainter) when near aphelion. It’s strange to think that had Pluto been near aphelion during the past century rather than the other way around, it may well have eluded detection!

This all means that a telescope will be necessary in your quest, and the more powerful the better. Pluto was just in range of a 6-inch aperture instrument about 2 decades ago. In 2013, we’d recommend at least an 8-inch scope and preferably larger to catch it. Pluto was an easy grab for us tracking it with the Flandrau Science Center’s 16-inch reflector back in 2006.

Pluto is also currently crossing a very challenging star field. With an inclination of 17.2° relative to the ecliptic, Pluto crosses the ecliptic in 2018 for the first time since its discovery in 1930. Pluto won’t cross north of the ecliptic again until 2179.

Pluto also crossed the celestial equator into southern declinations in 1989 and won’t head north again til 2107.

But the primary difficulty in spotting +14th magnitude Pluto lies in its current location towards the center of our galaxy. Pluto just crossed the galactic plane in early 2010 into a very star-rich region. Pluto has passed through some interesting star fields, including transiting the M25 star cluster in 2012 and across the dark nebula Barnard 92 in 2010.

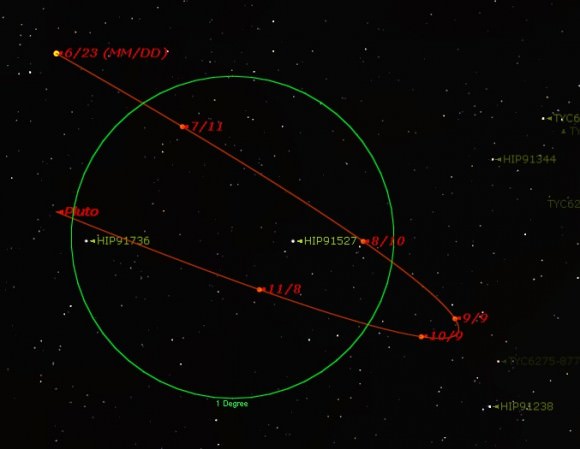

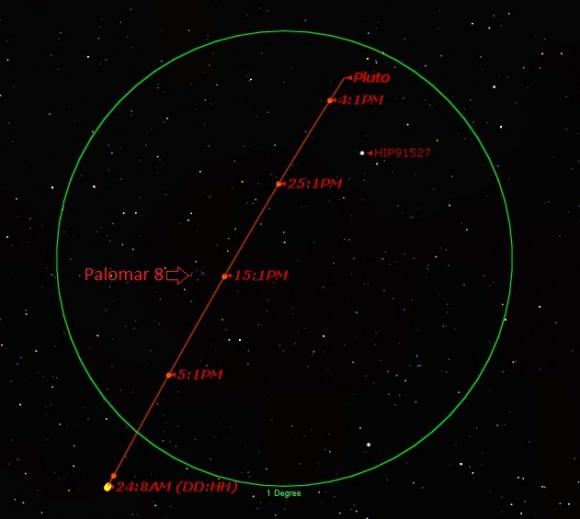

This year finds Pluto approaching the +6.7 magnitude star SAO 187108 (HIP91527). Next year, it will pass close to an even brighter star in the general region, +5.2 magnitude 29 Sagittarii. Mid-July also sees it passing very near the +10.9 magnitude globular cluster Palomar 8 (see above). This is another fine guidepost to aid in your quest.

So, how do you pluck a 14th magnitude object from a rich star field? Very carefully… and by noting the positions of stars at high power on successive nights. A telescope equipped with digital setting circles, a sturdy mount and pin-point tracking will help immeasurably. Pluto is currently located at:

Right Ascension: 18 Hours 44′ 30.1″

Declination: -19° 47′ 31″

Heavens-Above maintains a great updated table of planetary positions. It’s interesting to note that while Pluto’s planet-hood is hotly debated, few almanacs have removed it from their monthly planetary summary roundups!

You can draw the field, or photograph it on successive evenings and watch for Pluto’s motion against the background stars. It’s even possible to make an animation of its movement!

Pluto will once again reach conjunction on the far side of the Sun on January 1st 2014. Interestingly, 2013 is a rare year missing a “Plutonian-solar conjunction.” This happens roughly every quarter millennium, and last occurred in 1767. This is because conjunctions and oppositions of Pluto creep along our Gregorian calendar by about a one-to-two days per year.

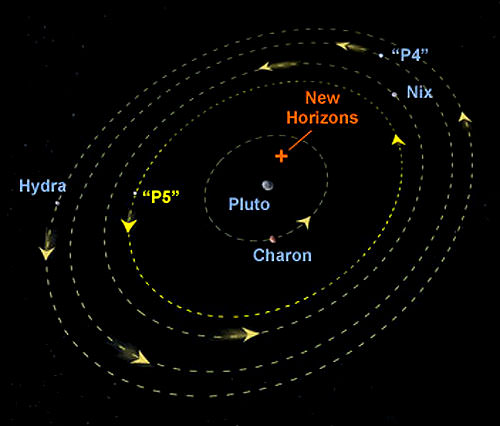

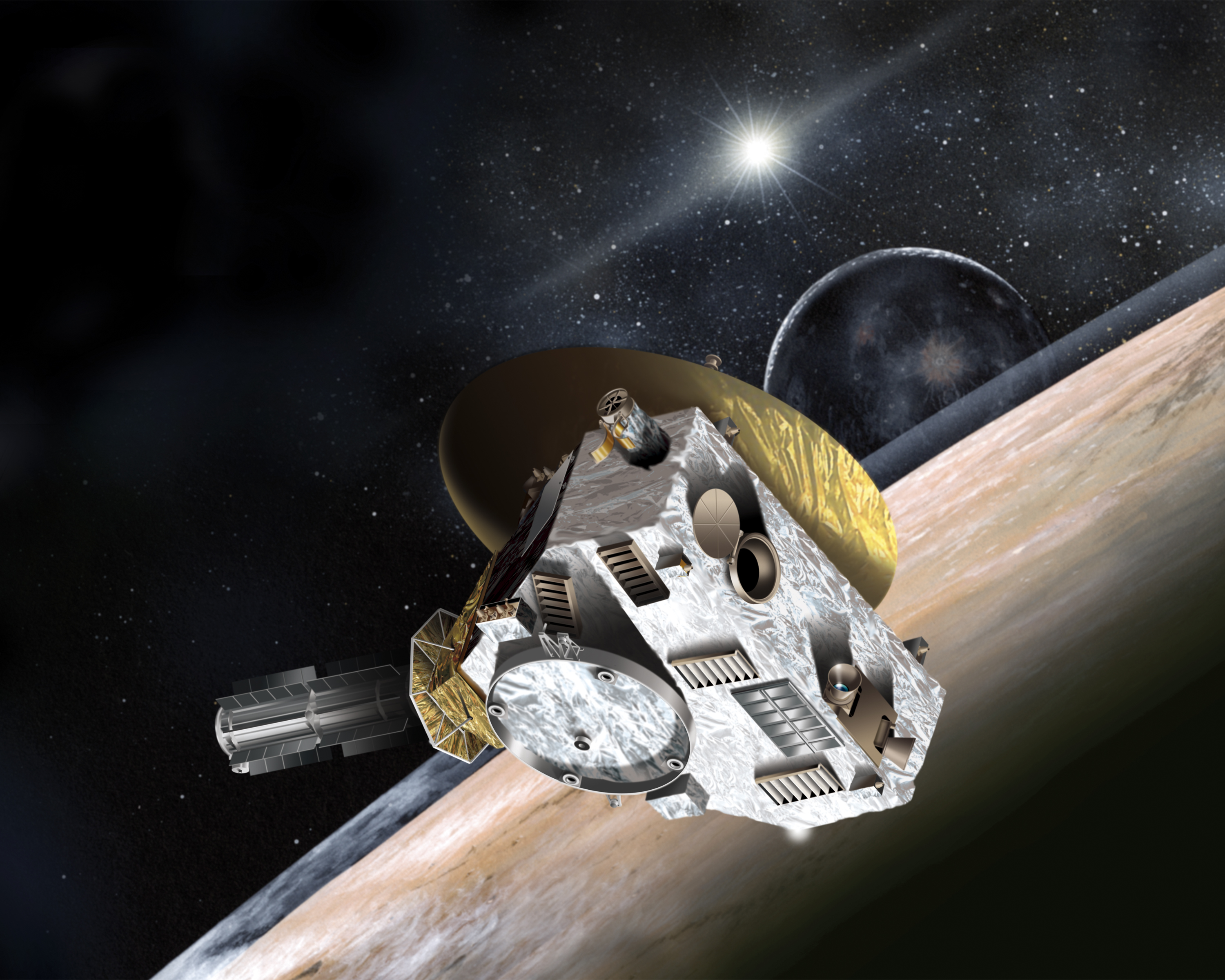

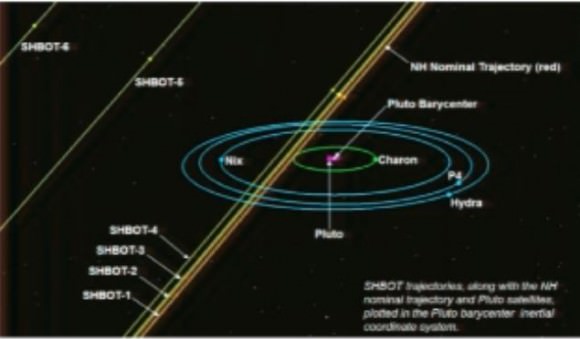

An Earthly ambassador also lies in the general direction of Pluto. New Horizons, launched in 2006 is just one degree to the lower left of 29 Sagittarii. Though you won’t see it through even the most powerful of telescopes, it’s fun to note its position as it closes in on Pluto for its July 2015 flyby.

Let us know your tales of triumph and tragedy as you go after this challenging object. Can you image it? See it through the scope? How small an instrument can you still catch it in? Seeing Pluto with your own eyes definitely puts you in a select club of visual observers…

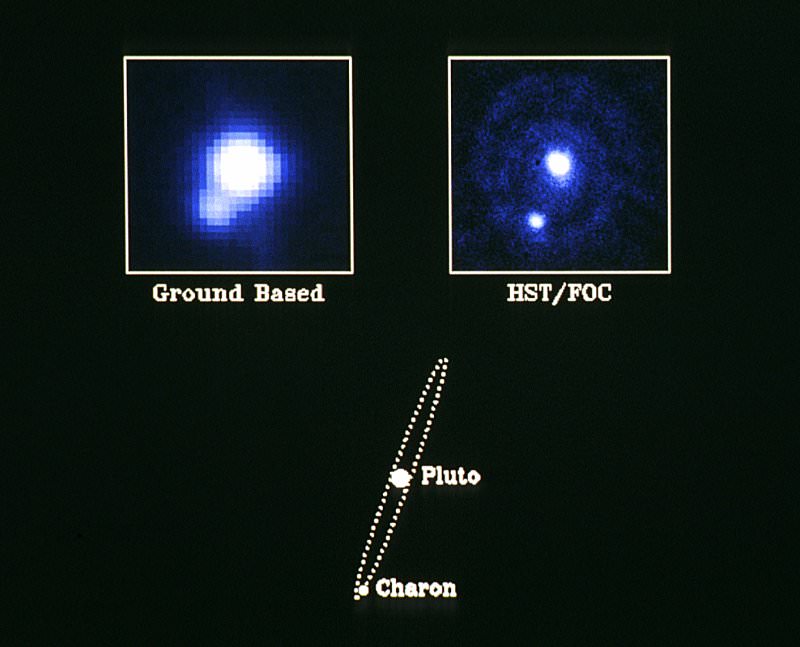

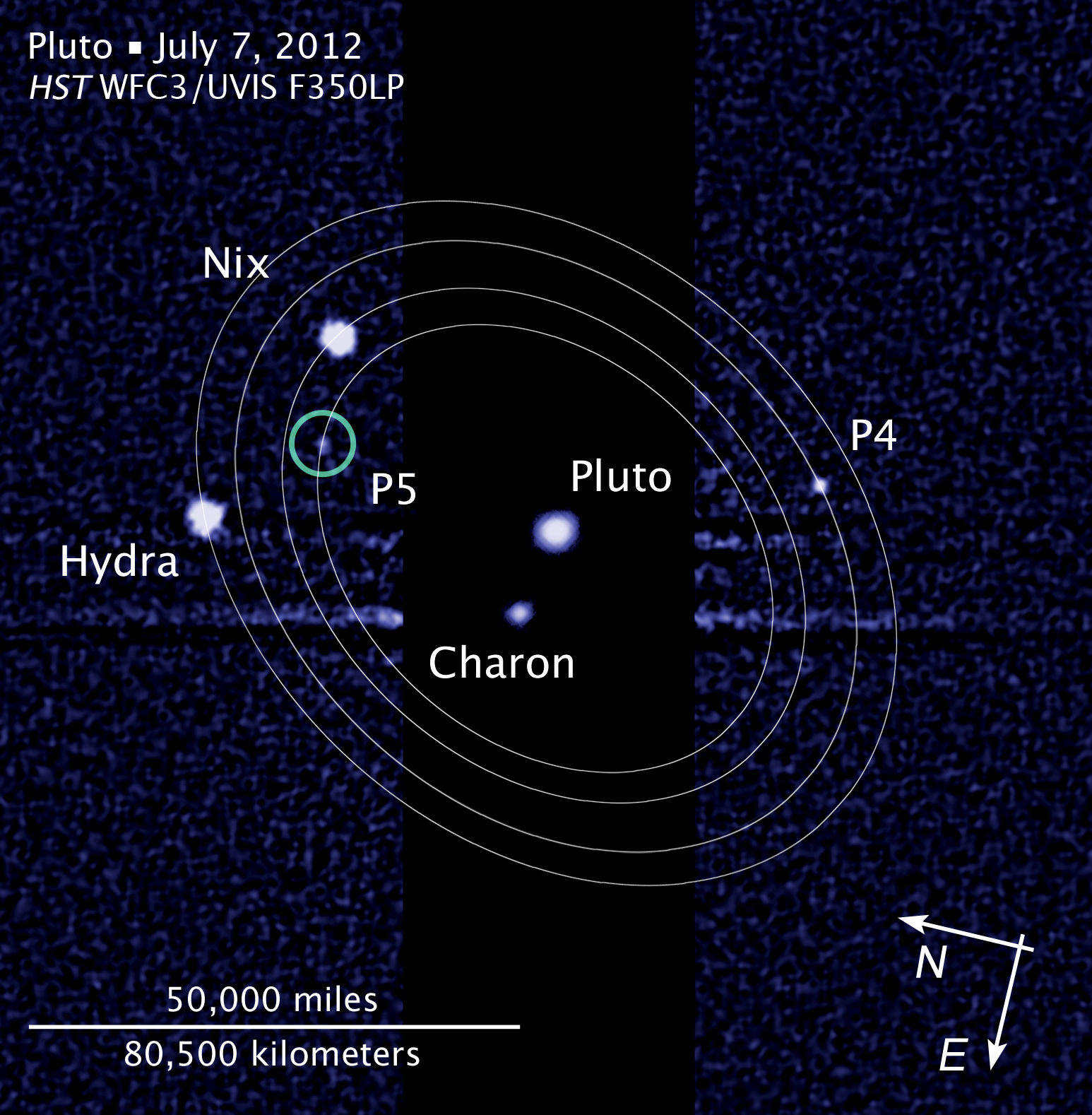

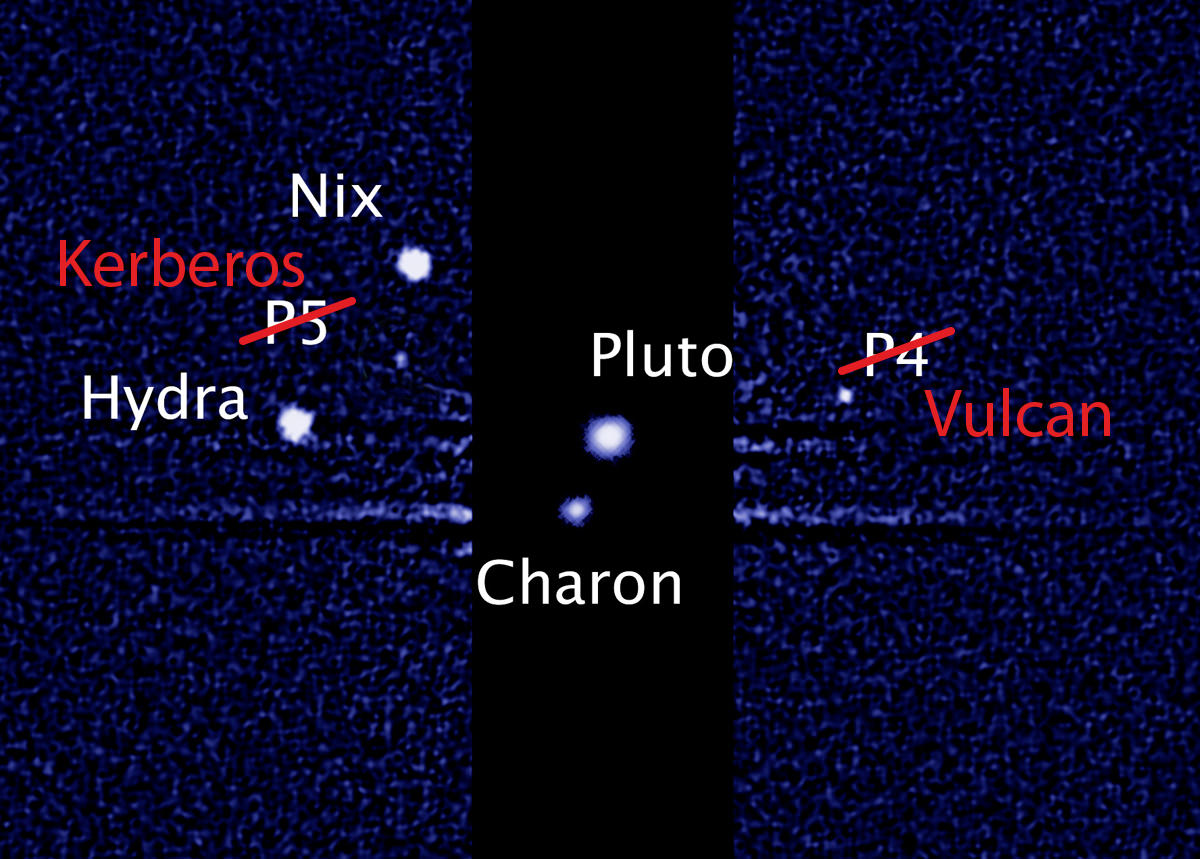

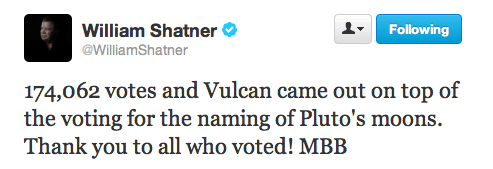

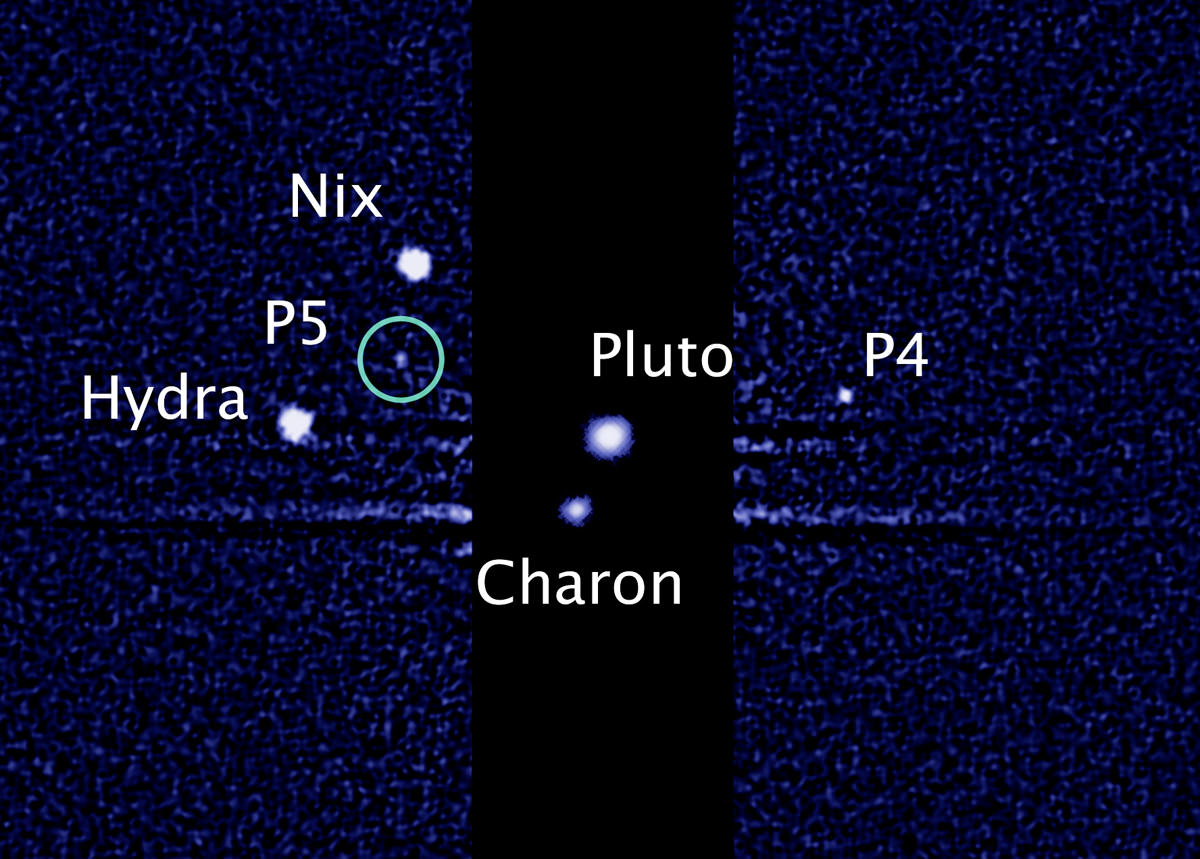

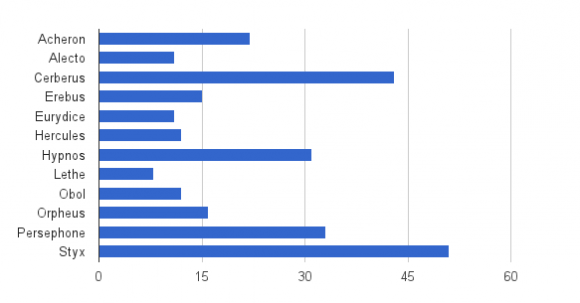

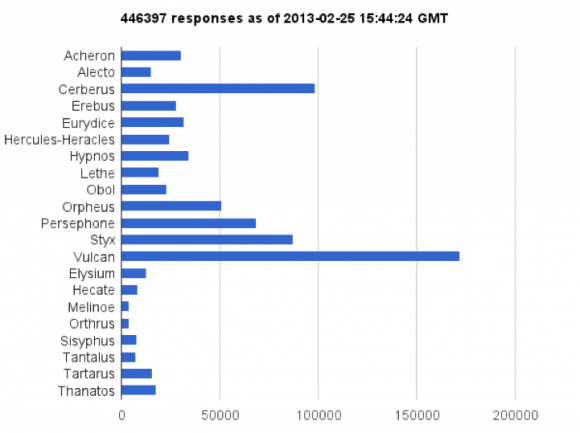

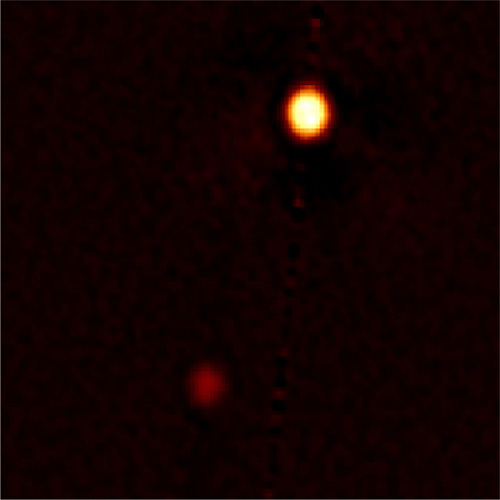

Still not enough of a challenge? Did you know that amateurs have actually managed to nab Pluto’s faint +16.8th magnitude moon Charon? Discovered in 35 years ago this month in 1978, this surely ranks as an ultimate challenge. In fact, discoverer James Christy proposed the name Charon for the moon on June 24th, 1978, as a tribute to his wife Charlene, whose nickname is “Char.” Since it’s discovery, the ranks of Plutonian moons have swollen to 5, including Nix, Hydra and two as of yet unnamed moons.

Be sure to join the hunt for Pluto this coming month. Its an uncharted corner of the solar system that we’re going to get a peek at in just over two years!