Pluto is certainly frigid, but new research has revealed its atmosphere is a bit warmer.

Astronomers using the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope have found unexpectedly large amounts of methane in Pluto’s atmosphere, which evidently helps it stay about 40 degrees warmer than the dwarf planet’s surface. The atmosphere warms to -180 degrees Celsius (-356 degrees Fahrenheit), compared to a surface that’s usually -220 degrees Celsius (-428 degrees Fahrenheit).

“With lots of methane in the atmosphere, it becomes clear why Pluto’s atmosphere is so warm,” said Emmanuel Lellouch of the Observatoire de Paris in France. Lellouch is lead author of the paper reporting the results, which is in press at the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics.

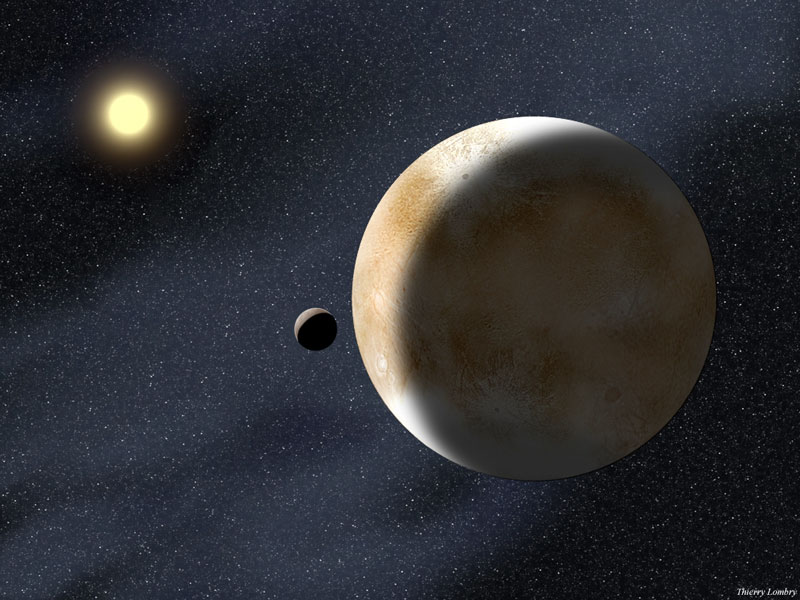

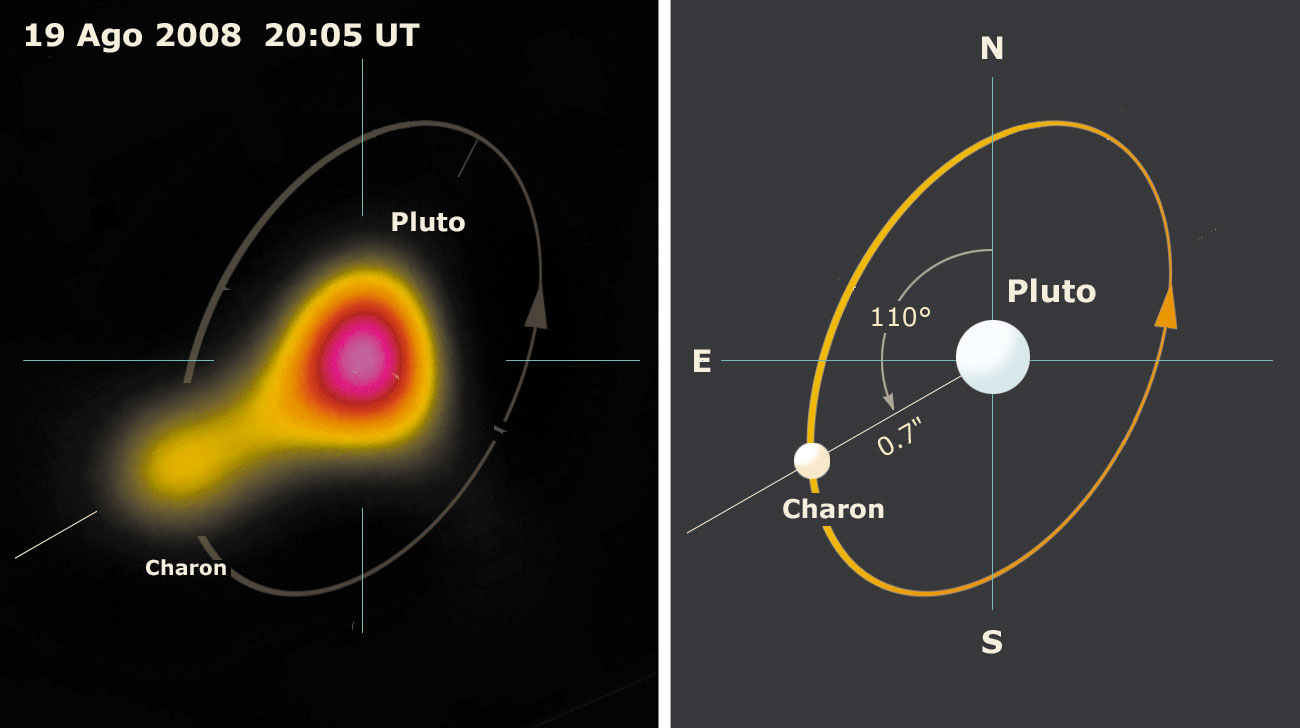

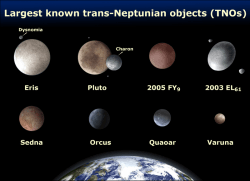

Pluto, which is about a fifth the size of Earth, is composed primarily of rock and ice and orbits about 40 times further from the Sun than the Earth.

It has been known since the 1980s that Pluto also has a thin, tenuous atmosphere. Abundant nitrogen, along with traces of methane and probably carbon monoxide, are held to the surface by an atmospheric pressure only about one hundred thousandth of that on Earth, or about 0.015 millibars. As Pluto moves away from the Sun, during its 248 year-long orbit, its atmosphere gradually freezes and falls to the ground. In periods when it is closer to the Sun — as it is now — the temperature of Pluto’s solid surface increases, causing the ice to sublimate into gas.

Until recently, only the upper parts of the atmosphere of Pluto could be studied. By observing stellar occultations, a phenomenon that occurs when a Solar System body blocks the light from a background star, astronomers were able to demonstrate that Pluto’s upper atmosphere was some 50 degrees warmer than the surface. Those observations couldn’t shed any light on the atmospheric temperature and pressure near Pluto’s surface. But unique, new observations made with the CRyogenic InfraRed Echelle Spectrograph (CRIRES), attached to ESO’s Very Large Telescope, have now revealed that the atmosphere as a whole, not just the upper atmosphere, has a mean temperature much less frigid than the surface.

Usually, air near the surface of the Earth is warmer than the air above it, largely because the atmosphere is heated from below as solar radiation warms the Earth’s surface, which, in turn, warms the layer of the atmosphere directly above it. Under certain conditions, this situation is inverted so that the air is colder near the surface of the Earth. Meteorologists call this an inversion layer, and it can cause smog build-up.

Most, if not all, of Pluto’s atmosphere is thus undergoing a temperature inversion: the temperature is higher, the higher in the atmosphere you look. The change is about 3 to 15 degrees per kilometer (.62 miles). On Earth, under normal circumstances, the temperature decreases through the atmosphere by about 6 degrees per kilometer.

The reason why Pluto’s surface is so cold is linked to the existence of Pluto’s atmosphere, and is due to the sublimation of the surface ice; much like sweat cools the body as it evaporates from the surface of the skin, this sublimation has a cooling effect on the surface of Pluto.

The CRIRES observations also indicate that methane is the second most common gas in Pluto’s atmosphere, representing half a percent of the molecules. “We were able to show that these quantities of methane play a crucial role in the heating processes in the atmosphere and can explain the elevated atmospheric temperature,” said Lellouch.

Two different models can explain the properties of Pluto’s atmosphere. In the first, the astronomers assume that Pluto’s surface is covered with a thin layer of methane, which will inhibit the sublimation of the nitrogen frost. The second scenario invokes the existence of pure methane patches on the surface.

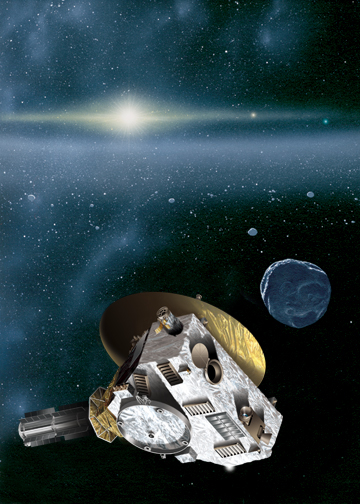

“Discriminating between the two will require further study of Pluto as it moves away from the Sun,” says Lellouch. “And of course, NASA’s New Horizons space probe will also provide us with more clues when it reaches the dwarf planet in 2015.”

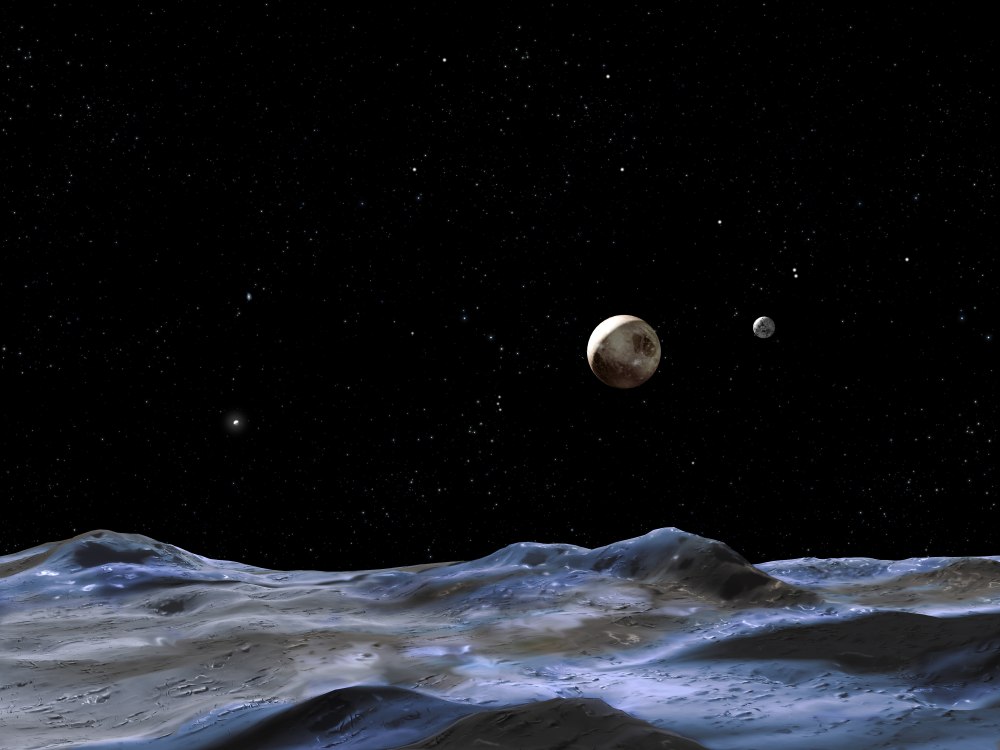

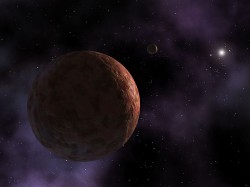

LEAD IMAGE CAPTION: Artist’s impression of how the surface of Pluto might look, if patches of pure methane rest on the surface. At the distance of Pluto, the Sun appears about 1,000 times fainter than on Earth. Credit: ESO

Source: ESO