Artist impression of the New Horizons spacecraft sweeping past Pluto. Image credit: JHUAPL/SwRI. Click to enlarge.

If all goes well, the first mission to the farthest known planet in our Solar System will launch in early 2006, and give us our first detailed views of Pluto, its moon Charon, and the Kuiper Belt Region, while completing NASA’s reconnaissance of all the planets in our Solar System.

“We’re going to a planet that we’ve never been to before,” said Dr. Alan Stern, Principal Investigator for the New Horizons mission to Pluto. “This is like something out of a NASA storybook, like in the 60’s and 70’s with all the new missions that were happening then. But this is exploration for a new century; it’s something bold and different. Being the first mission to the last planet really ‘revs’ me. There’s something special about going to a new frontier, about

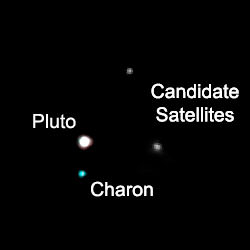

Pluto is so far away (5 billion km or 3.1 billion miles when New Horizons reaches it) that no telescope, not even the Hubble Space Telescope, has been able to provide a good image of the planet, and so Pluto is a real mystery world. The existence of Pluto has only been known for 75 years, and the debate continues about its classification as a planet, although most planetary scientists classify it in the new class of planets called Ice Dwarfs. Pluto is a large, ice-rock world, born in the Kuiper Belt area of our solar system. Its moon, Charon, is large enough that some astronomers refer to the two as a binary planet. Pluto undergoes seasonal change and has an elongated and enormous 248-year orbit which causes the planet’s atmosphere to cyclically dissipate and freeze out, but later be replenished when the planet returns closer to the sun.

New Horizons will provide the first close-up look at Pluto and the surrounding region. The grand piano-sized spacecraft will map and analyze the surface of Pluto and Charon, study Pluto’s escaping atmosphere, look for an atmosphere around Charon, and perform similar explorations of one or more Kuiper Belt Objects.

The spacecraft, built at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory, is currently being flight tested at the Goddard Space Flight Center. Dr. Stern has been planning a mission to Pluto for quite some time, surviving through the various on-again, off-again potential missions to the outer solar system.

“I’m feeling very good about the mission,” he said in an interview from his office at the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado. “I’ve been working on this project for about 15 years, and the first 10 years we couldn’t even get it out of the starting blocks. Now we’ve not only managed to get it funded, but we have built it and we are really looking forward to flying the mission soon if all continues to go well.”

Of the hurdles remaining to be cleared before launch, one looms rather large. New Horizons’ systems are powered by a Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generator (RTG), where heat released from the decay of radioactive materials is converted into energy. This type of power system is essential for a mission going far from the Sun like New Horizons where solar power is not an option, but it has to be approved by both NASA and the White House. The 45-day public comment period ended in April 2005, so the project now awaits final, official approval. Meanwhile, the New Horizons mission teams prepare for launch.

“We still have a lot of work in front of us,” Stern said. “All this summer we’re testing and checking out the spacecraft and the components, getting all the bugs out, and making sure its launch ready, and flight ready. That will take us through September and in October we hope to bring the spacecraft to the Cape.”

The month-long launch window for New Horizons opens on January 11, 2006.

New Horizons will be the fastest spacecraft ever launched. The launch vehicle combines an Atlas V first stage, a Centaur second stage, and a STAR 48B solid rocket third stage.

“We built the smallest spacecraft we could get away with that has all the things it needs: power, communication, computers, science equipment and redundancy of all systems, and put it on the biggest possible launch vehicle,” said Stern. “That combination is ferocious in terms of the speed we reach in deep space.”

At best speed, the spacecraft will be traveling at 50 km/second (36 miles/second), or the equivalent of Mach 85.

Stern compared the Atlas rocket to other launch vehicles. “The Saturn V took the Apollo astronauts to the moon in 3 days,” he said. “Our rocket will take New Horizons past the moon in 9 hours. It took Cassini 3 years to get to Jupiter, but New Horizons will pass Jupiter in just 13 months.”

Still, it will take 9 years and 5 months to cross our huge Solar System. A gravity assist from Jupiter is essential in maintaining the 2015 arrival date. Not being able to get off the ground early in the launch window would have big consequences later on.

“We launch in January of 2006 and arrive at Pluto in July of 2015, best case scenario,” said Stern. “If we don’t launch early in the launch window, the arrival date slips because Jupiter won’t be in as good a position to give us a good gravity assist.”

New Horizons has 18 days to launch in January 2006 to attain a 2015 arrival. After that, Jupiter’s position moves so that for every 4 or 5 days delay in launch means arriving at Pluto year later. By February 14 the window closes for a 2020 arrival. New Horizons can try to launch again in early 2007, but then the best case arrival year is 2019.

New Horizons will be carrying seven science instruments:

- Ralph: The main imager with both visible and infrared capabilities that will provide color, composition and thermal maps of Pluto, Charon, and Kuiper Belt Objects.

- Alice: An ultraviolet spectrometer capable of analyzing Pluto’s atmospheric structure and composition.

- REX: The Radio Science Experiment that measures atmospheric composition and surface temperature with a passive radiometer. REX also measures the masses of objects New Horizons flies by.

- LORRI: The Long Range Reconnaissance Imager has a telescopic camera that will map Pluto?s far side and provide geologic data.

- PEPSSI: The Pluto Energetic Particle Spectrometer Science Investigation that will measure the composition and density of the ions escaping from Pluto’s atmosphere.

- SWAP: Solar Wind Around Pluto, which will measure the escape rate of Pluto?s atmosphere and determine how the solar wind affects Pluto.

- SDC: The Student Dust Counter will measure the amount of space dust the spacecraft encounters on the voyage. This instrument was designed and will be operated by students at the University of Colorado in Boulder.

Stern says the first part of the flight will keep the mission teams busy, as they need to check out the entire spacecraft, and execute the Jupiter fly-by at 13 months.

“The middle years will be long and probably — and hopefully — pretty boring,” he said, but will include yearly spacecraft and instrument checkouts, trajectory corrections, instrument calibrations and rehearsals the main mission. During the last three years of the interplanetary cruise mission teams will be writing, testing and uploading the highly detailed command script for the Pluto/Charon encounter, and the mission begins in earnest approximately a year before the spacecraft arrives at Pluto, as it begins to photograph the region.

A mission to Pluto has been a long time coming, and is popular with a wide variety of people. Children seem to have an affinity for the planet with the cartoon character name, while the National Academy of Sciences ranked a mission to Pluto as the highest priority for this decade. In 2002, when it looked as though NASA would have to scrap a mission to Pluto for budgetary reasons, the Planetary Society, among others, lobbied strongly to Congress to keep the mission alive.

Stern said the mission’s website received over a million hits the first month it was active, and the hit rate hasn’t diminished. Stern writes a monthly column on the website, http://pluto.jhuapl.edu , where you can learn more details about the mission and sign-up to have your name sent to Pluto along with the spacecraft.

While Stern is understandably excited about this mission, he says that any chance to explore is a great opportunity.

“Exploration always opens our eyes,” he said. “No one expected to find river valleys on Mars, or a volcano on Io, or rivers on Titan. What do I think we’ll find at Pluto-Charon? I think we’ll find something wonderful, and we expect to be surprised.”