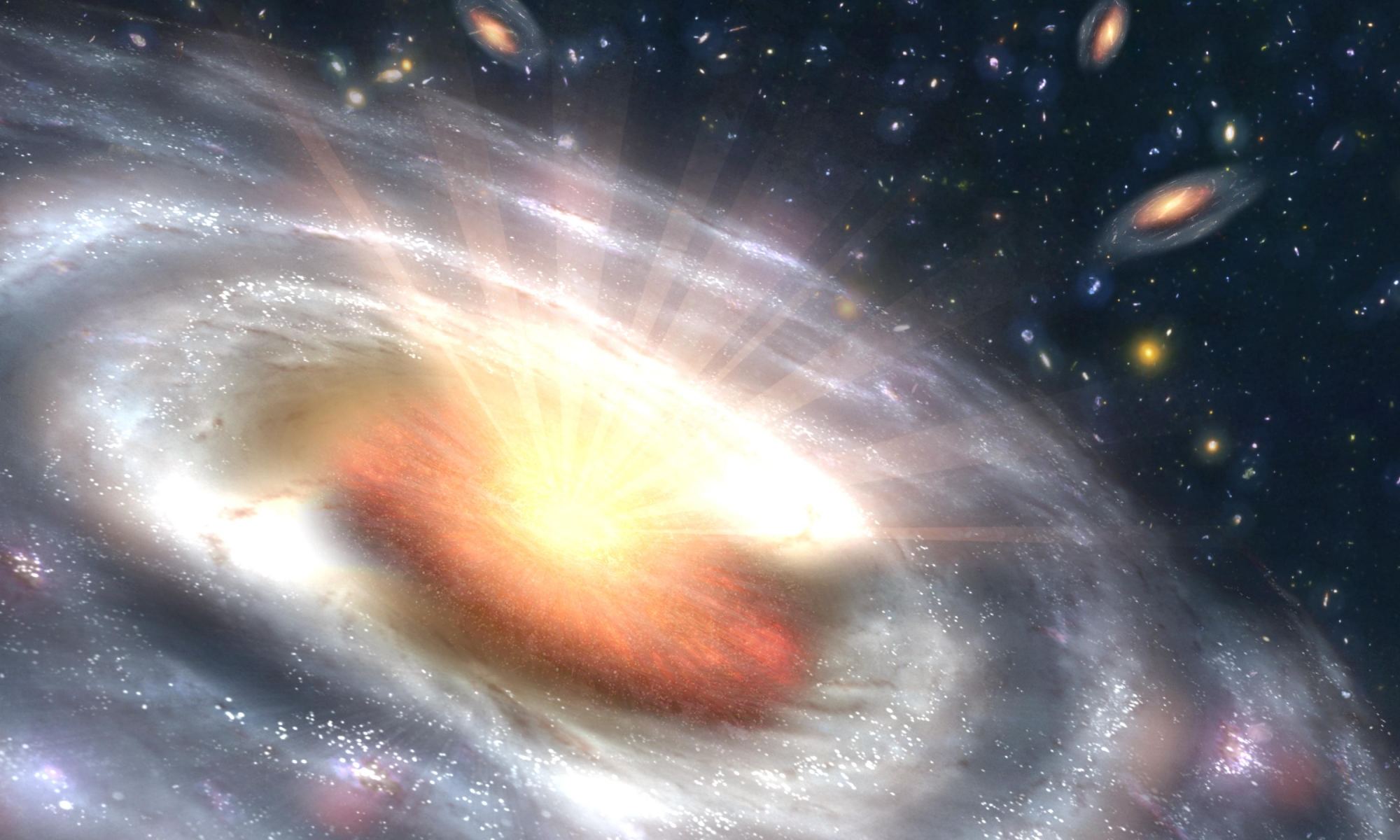

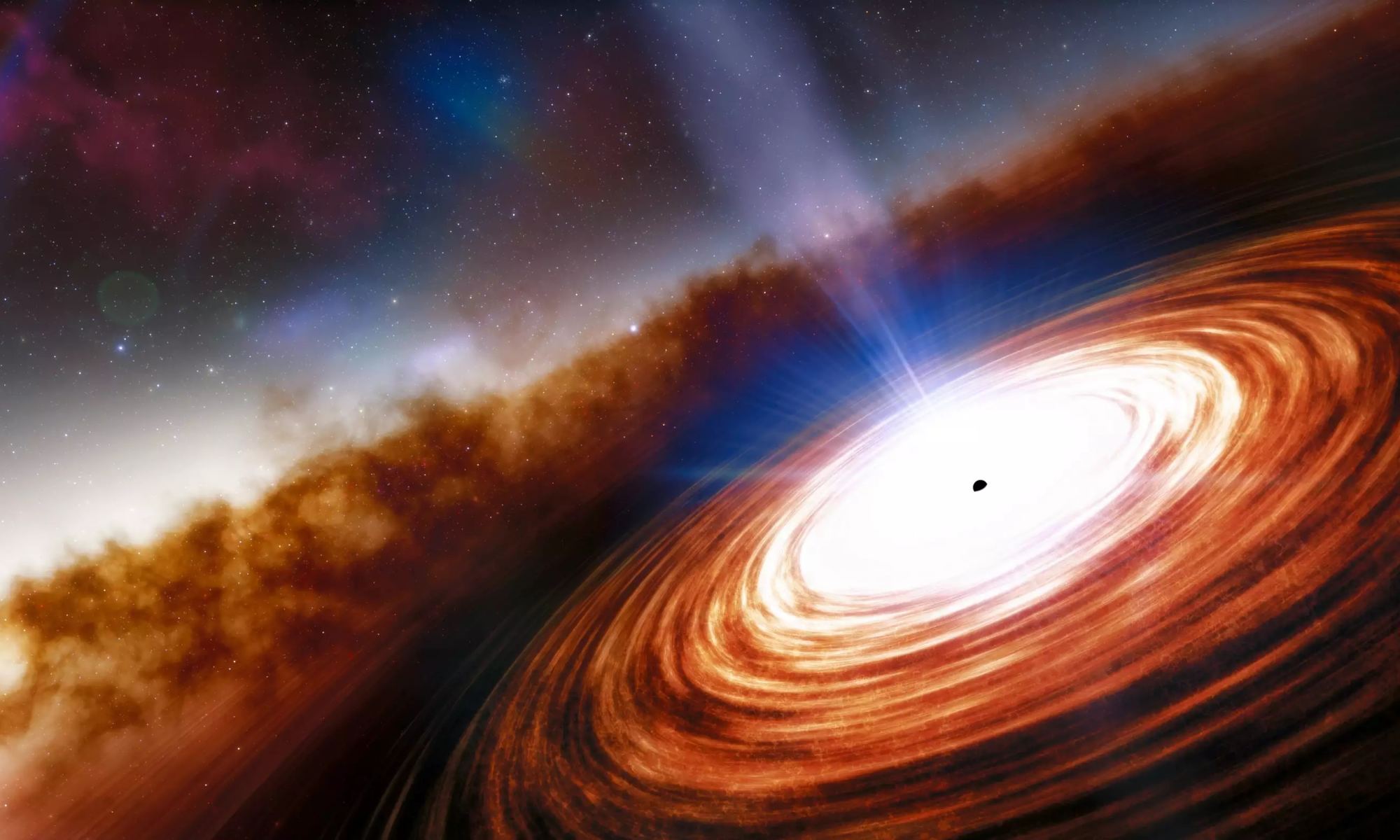

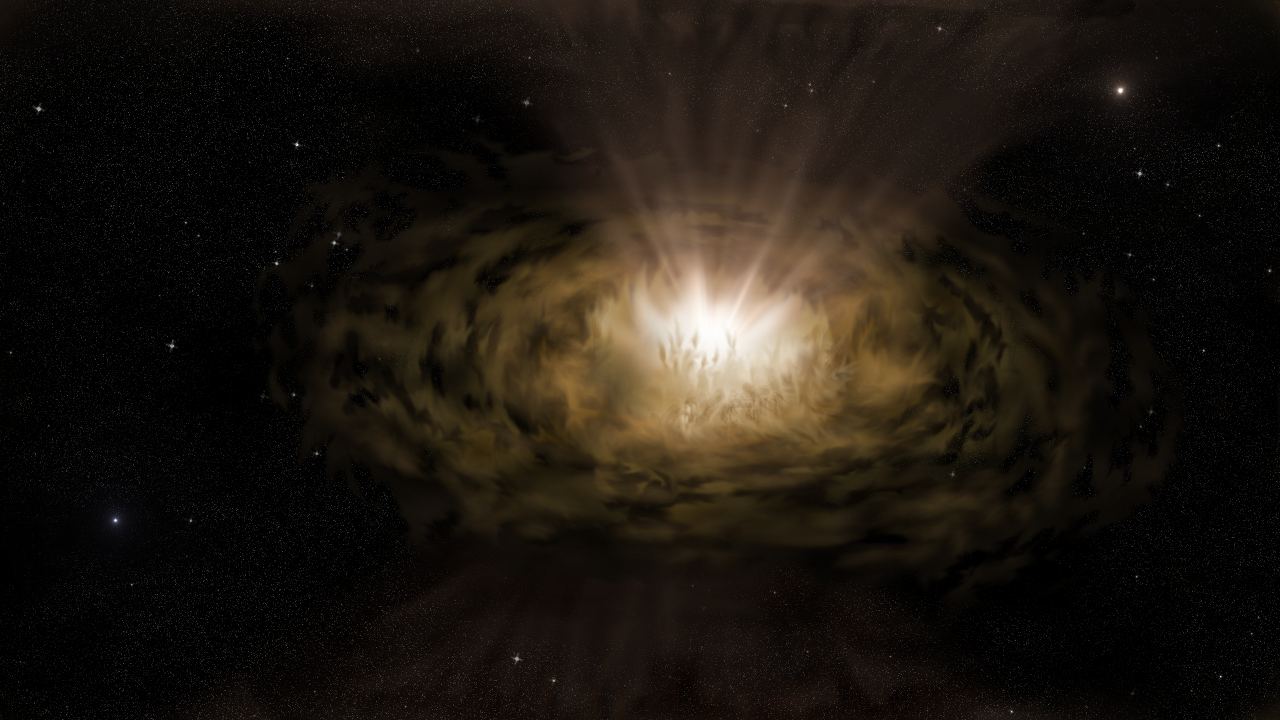

In the 1970s, astronomers deduced that the persistent radio source coming from the center of our galaxy was actually a supermassive black hole (SMBH). This black hole, known today as Sagittarius A*, is over 4 million solar masses and is detectable by the radiation it emits in multiple wavelengths. Since then, astronomers have found that SMBHs reside at the center of most massive galaxies, some of which are far more massive than our own! Over time, astronomers observed relationships between the properties of galaxies and the mass of their SMBHs, suggesting that the two co-evolve.

Using the GRAVITY+ instrument at the Very Large Telescope Interferometer (VLTI), a team from the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics (MPE) recently measured the mass of an SMBH in SDSS J092034.17+065718.0. At a distance of about 11 billion light-years from our Solar System, this galaxy existed when the Universe was just two billion years old. To their surprise, they found that the SMBH weighs in at a modest 320 million solar masses, which is significantly under-massive compared to the mass of its host galaxy. These findings could revolutionize our understanding of the relationship between galaxies and the black holes residing at their centers.

Continue reading “Astronomers are Getting Really Good at Weighing Baby Supermassive Black Holes”