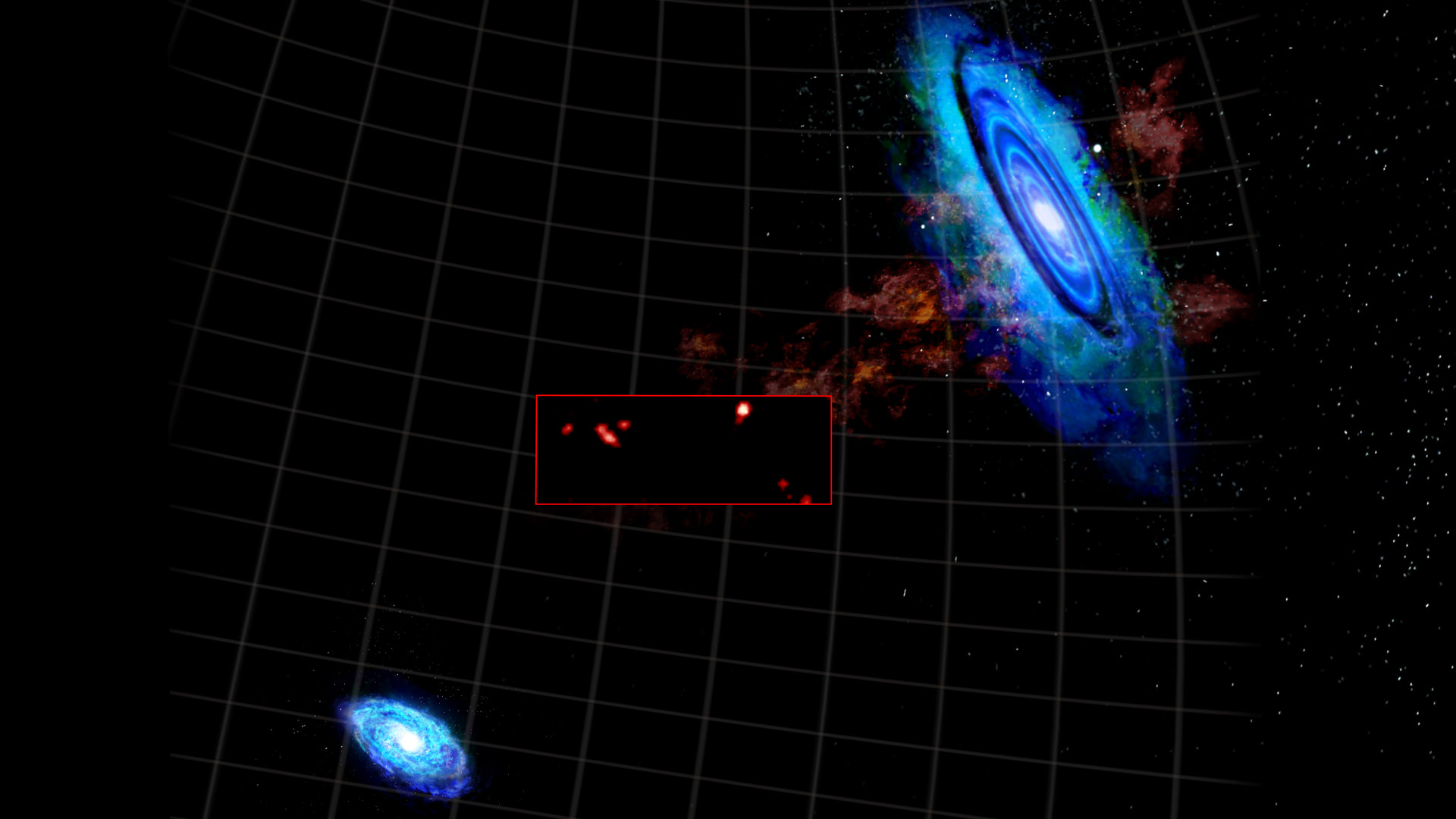

The Universe is sizzling with undiscovered phenomena. Only last month astronomers heard four unexpected bumps in the night. These Fast Radio Bursts released torrents of energy, each occurred only once, and lasted a few thousandths of a second. Their origin has since mystified astronomers.

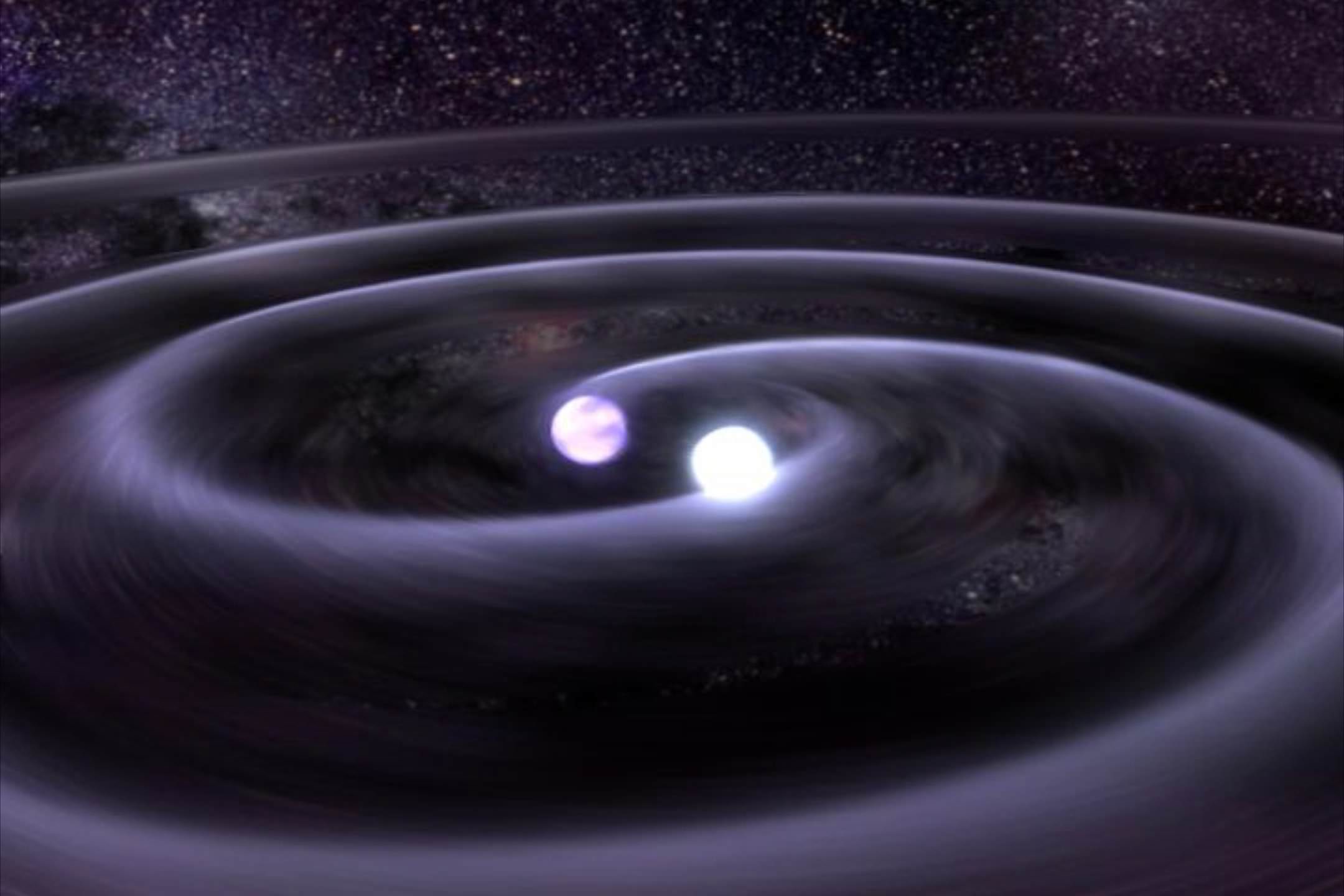

Dismissing my first guess, which includes a feverish Jodie Foster verifying the existence of extraterrestrial life, astronomers have found a more likely answer. Two neutron stars collide, but before doing so produce a quick burst of radio emission, which we later observe as a Fast Radio Burst.

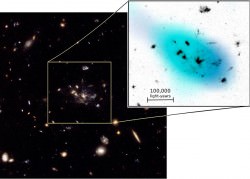

Our first hint? These Fast Radio Bursts are extra-galactic in origin. The exact distance is quantifiable from a “dispersion measure – the frequency dependent time delay of the radio signal,” Dr. Tomonori Totani, lead author on the paper, told Universe Today. “This is proportional to the number of electrons along the line of sight.”

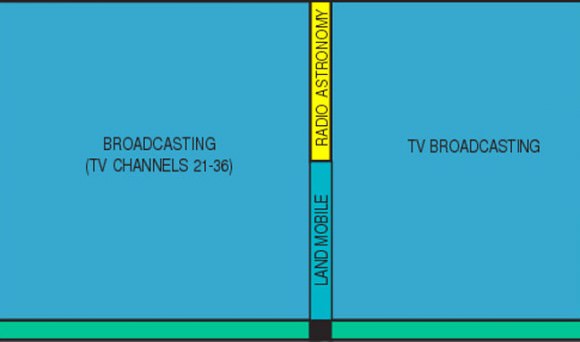

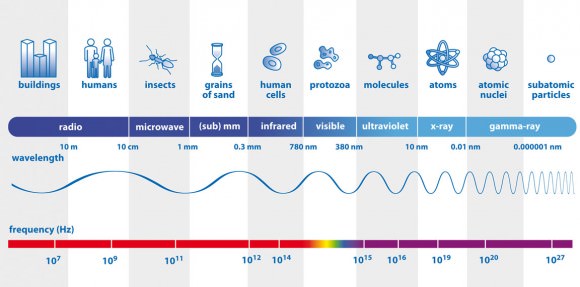

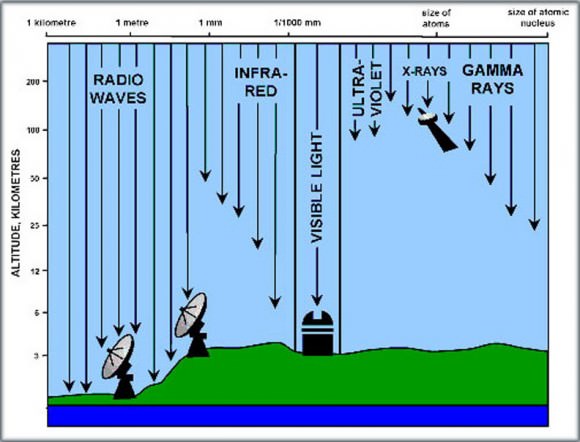

For all bursts, the short-wavelength component arrived at the telescope a fraction of a second before the longer wavelengths. This is due to an effect known as interstellar dispersion: through any medium, longer-wavelength light moves slightly slower than short-wavelength light.

Light from extra-galactic objects will have to travel through intergalactic space, which is teeming with electrons in clouds of cold plasma. The farther the light travels, the more electrons it will have to travel through, and the greater the time delay between arriving wavelength components. By the time light reaches the Earth, it has been dispersed, and the amount of dispersion is directly correlated with distance.

These Fast Radio Bursts are likely to have originated anywhere from 5 to 10 billion light years away.

While the exact source of these Fast Radio Bursts has been highly debated, a recent hypothesis concludes that they are the result of merging neutron stars in the distant Universe.

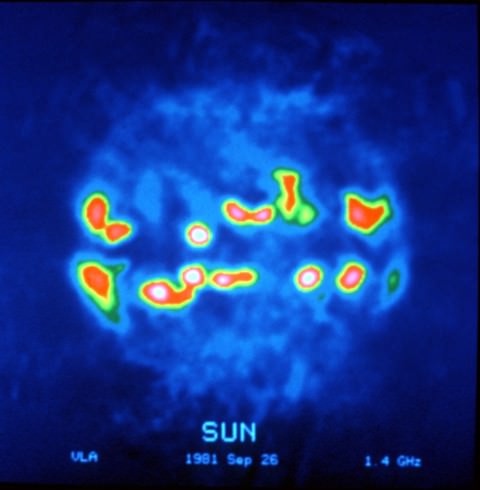

In the final milliseconds before merging, the rotation periods of the two neutron stars synchronize – they become tidally locked to one another as the Moon is tidally locked to the Earth. At this point their magnetic fields also synchronize. Energetic charged particles spiral along the strong magnetic field lines and emit a beam of radio synchrotron emission.

Known neutron star magnetic field strengths are consistent with the radio flux observed in these Fast Radio Bursts. The emission then ceases in a few milliseconds when the two neutron stars have collided, which explains the short duration of these Fast Radio Bursts.

Not only does this mechanism describe both the high energy and the time duration of these bursts, but they’re inferred occurrence rate as well. It’s likely that 100,000 Fast Radio Bursts occur each day. This matches the likely neutron star merger rate.

Merging neutrons stars will also create gravitational waves – ripples in the curvature of spacetime that propagate away from the event. Dr. Totani emphasized that the next step will be to perform a correlated search of gravitational waves and Fast Radio Bursts. Such a fast rate estimate is certainly good news for scientists hoping to detect gravitational waves in the nearby future.

The Universe is bursting with energy – literally – every 10 seconds, and until recently we simply had no idea. This recently discovered phenomenon is likely to be the center of a new active area of research. And I have no doubt that it will lead to exciting discoveries that just may break trends and burst into new territories.

The discovery paper may be found here, while the paper analyzing neutron stars as a likely source may be found here.