Next weekend’s launch of the Delta-4 Heavy has been postponed. The launch, which was to take place at Cape Canaveral, has been delayed due to unspecified payload issues. The launch is for the National Reconnaissance Office, a fairly secretive branch of the U.S. Government that’s in charge of the nation’s spy satellites. As such, they aren’t revealing too many details about the launch, or the postponement.

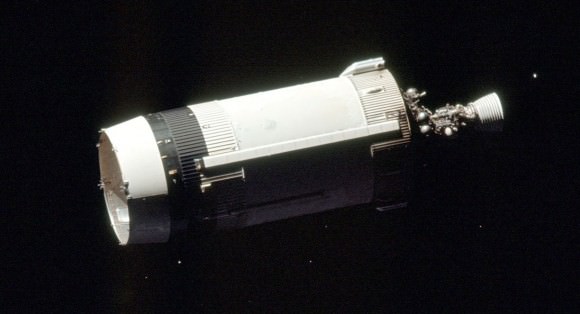

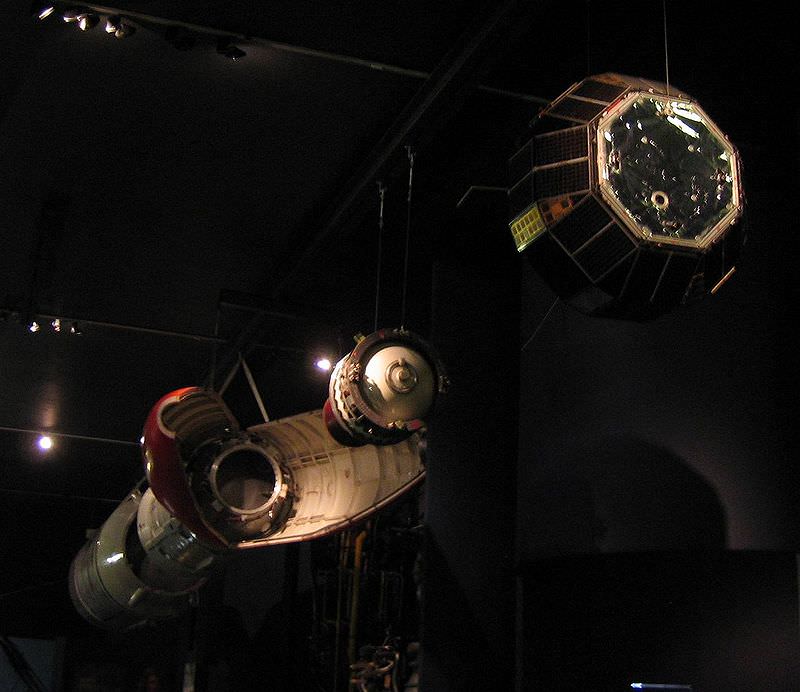

The Delta-4 Heavy rocket is a combination of three booster cores from the Delta Medium. Each one of these cores is a liquid hydrogen-fuelled engine that forms the Delta-4 Medium’s first stage. They’re mounted together to make a trio of engines, capped with a cryogenic upper stage.

The Delta-4 Heavy weighs 725000 kg (1.6 million lbs.) when it’s fully fuelled. It’s 71.6 meters (235 ft.) tall, and when it’s ignited it unleashes a whopping 2.1 million lbs. of thrust.

This configuration makes it the USA’s largest rocket, and it carries critical payloads for the government. These include not only spy satellites, but also an un-crewed test flight of the Orion Multi-Purpose Crew Vehicle.

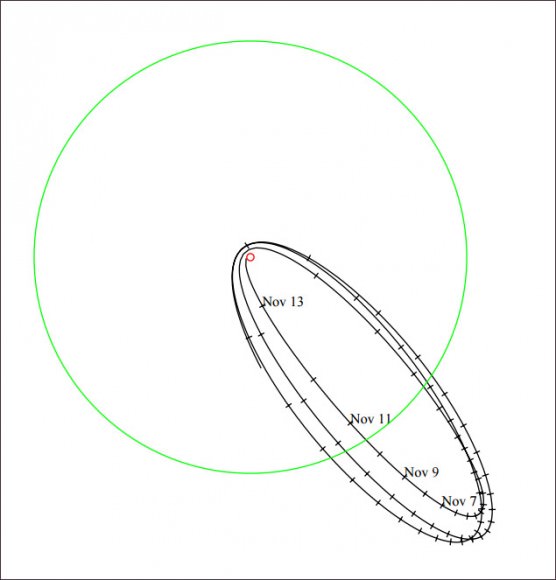

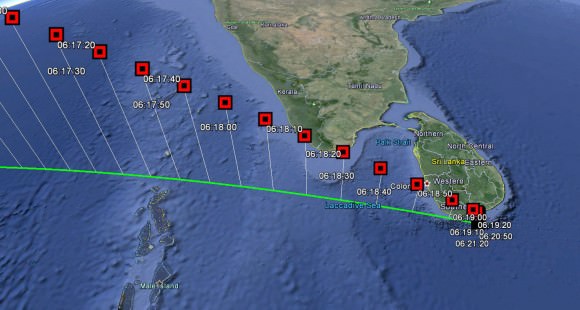

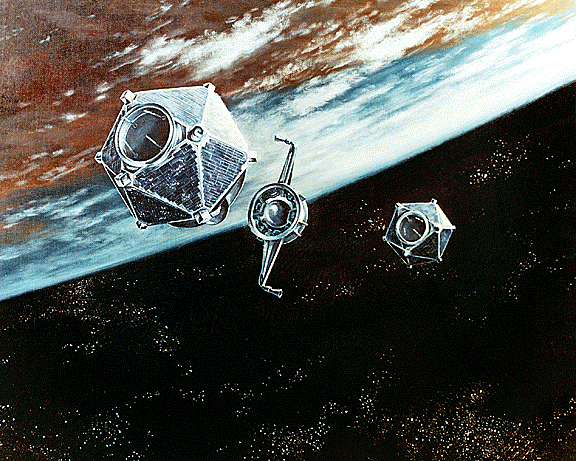

The cancelled mission, named NROL-37, was supposed to lift an Orion 9 satellite into orbit. Orion satellites are signal interception satellites, and are placed in geo-stationary orbits to collect radio emissions. One of the Orion satellites is believed to be “… the largest satellite in the world,” according to Bruce Carlson, NRO Director. This probably refers to the size of the satellites antenna, which is over 100m (330ft.) in diameter.

The Delta-4 Heavy (D4H) is considered the largest rocket in the world. The D4H can lift a whopping 28,790 kg into Low Earth Orbit (LEO.) Contemporaries like the Ariane 5 (ECA & ES versions) can lift 21,000 kg into LEO.

It won’t be the most powerful rocket for much longer though. The upcoming Falcon Heavy from SpaceX will lift an enormous 54,400 kg into LEO. Also being developed is the US Space Launch System (SLS), which, in its Block2 configuration, will lift 130,700 kg. The Chinese are in on the most powerful rocket game too, with their Long March 9 rocket. Under development now, it is projected to lift 130,000 kg into LEO, just a shade less than the SLS.

Oddly enough, the old Saturn V could lift 140,000 kg, putting all its successors to shame. The Saturn V was developed for the Apollo Program, and was also used to launch Skylab. Saturn V was in use from 1967 to 1973. To date, the Saturn V is the only rocket capable of transporting human beings beyond LEO.

As for the cancelled launch, no date has been set yet for the next launch. Once it is launched, it will mark the 9th D4H configuration to fly, and the 32nd Delta 4 launch since 2002. It will also be the 6th time the D4H has launched for the NRO.

Universe Today’s Ken Kremer is at Cape Canaveral for this launch, and will report on it, and no doubt provide some stunning photos. Check back with us to see Ken’s coverage.

Martian Eye Candy: A beautiful picture of some dunes on the surface of Mars. Thanks MRO! (Image: NASA/JPL-Caltech/University of Arizona)

Martian Eye Candy: A beautiful picture of some dunes on the surface of Mars. Thanks MRO! (Image: NASA/JPL-Caltech/University of Arizona)