[/caption]

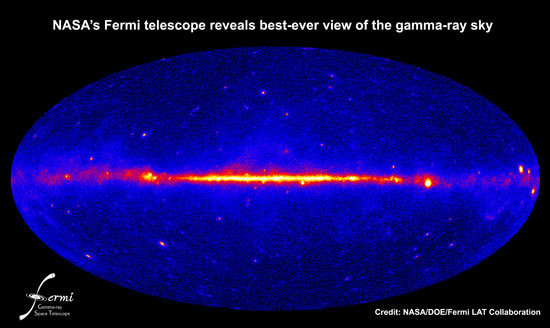

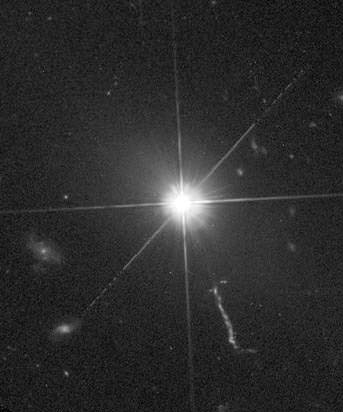

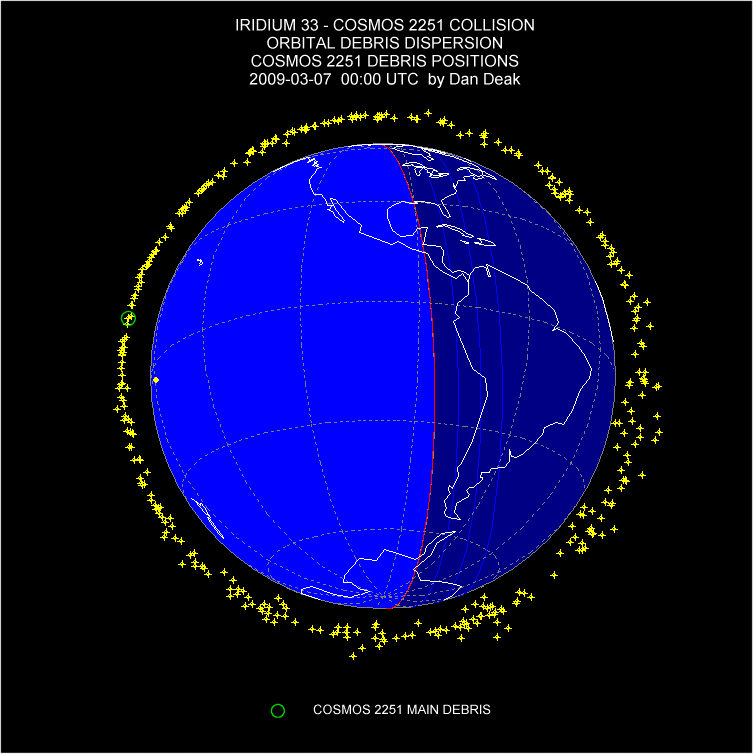

NASA tracked a piece of orbital debris that came fairly close to space shuttle Atlantis and the Hubble Space Telescope Wednesday evening, but decided no evasive maneuver was required. A 4 inch (10 cm) chunk of a Chinese satellite that was destroyed in a 2007 anti-satellite test came within 1.7 miles (2.8 km) ahead and 150 meters below Atlantis at its closest approach. These potential orbital impacts seem to be occurring routinely for the ISS, and previous shuttle missions have been forced to maneuver out of the way to avoid collisions. The satellite collision in February destroyed a functional satellite, and seemingly, it will be only a matter of time until a serious impact could endanger human lives in orbit. Last week, experts gathered at the International Interdisciplinary Congress on Space Debris, at McGill University in Montreal, Canada and concluded that action must be taken now to reduce the threat to both human spaceflight and satellites from destructive space debris.

“Space debris is primarily a global issue. Global problems need globally solutions, which must be effectively implemented internationally as well as nationally,” said McGill University’s Ram Jakhu, Chair of the Congress.

Over the past decade and a half, the world’s major space agencies have been developing a set of orbital debris mitigation guidelines aimed at stemming the creation of new space debris and lessening the impact of existing debris on satellites and human spaceflight. Most agencies are in the process of implementing or have already implemented these voluntary measures which include on-board passive measures to eliminate latent sources of energy related to batteries, fuel tanks, propulsion systems and pyrotechnics.

But the growing number of developing countries that are launching using satellites, and they need to be encouraged to use these measures as well.

Last week’s Congress suggested that the mitigation guidelines should become mandatory instead of just voluntary, and another possibility mentioned was the establishment of an international regime for dealing with orbital debris similar to the Missile Technology Control Regime, or perhaps the Limited Test Ban Treaty of 1963. There are a variety of other means within international law as well, including codes, declarations and treaties.

Up until now, the debris mitigation process has been focused mainly on the technical aspects, with an enormous amount of research producing excellent recommendations, noted Brian Weeden, Technical Consultant for the Secure World Foundation.

“However, the community is now starting to focus on the legal aspect, which is critical for broadening and strengthening the adoption of debris mitigation guidelines and space safety in general,” Weeden said.

Weeden explained that the recent Congress explored lessons from terrestrial environmental pollution law as well as maritime law that could be applicable to outer space. Furthermore, international law isn’t necessarily the only method for implementing the guidelines. “We are also looking at a variety of other mechanisms, to include economics and industrial standards,” he said.

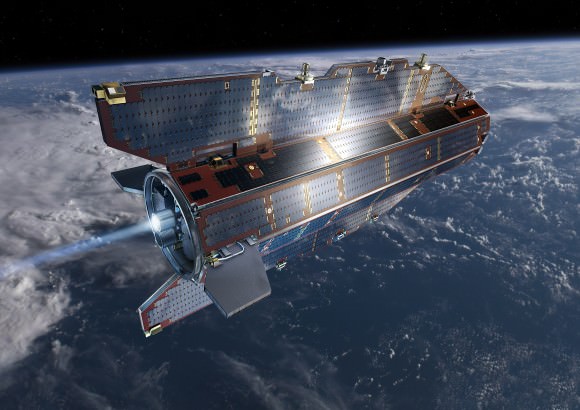

Additionally, researchers are moving towards the next phase of scientific study. “There is an emerging consensus among the technical community that simply preventing creation of new debris is not going to be enough,” Weeden emphasized.

“At some point we will need to actively remove debris from orbit. Fortunately, new studies are showing that removing as few as five or six objects per year could stabilize the debris population over the long term. The big question right now is which objects to remove first and what is the best method to do so.”

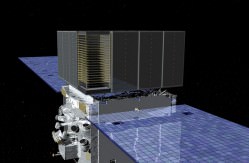

Some of the options for removing space debris include a “space broom” concept that NASA proposed in 1996 called Project Orion, frying space trash with ground-based lasers, an inflatable set of space tongs that could grab and tow objects, or a space vacuum similar to the Planet Eater, which devoured spaceships in an episode of “Star Trek.”

Any of these concepts would require substantial leaps in technology before they are feasible.

Sources: Secure World Foundation, Wall Street Journal