[/caption]

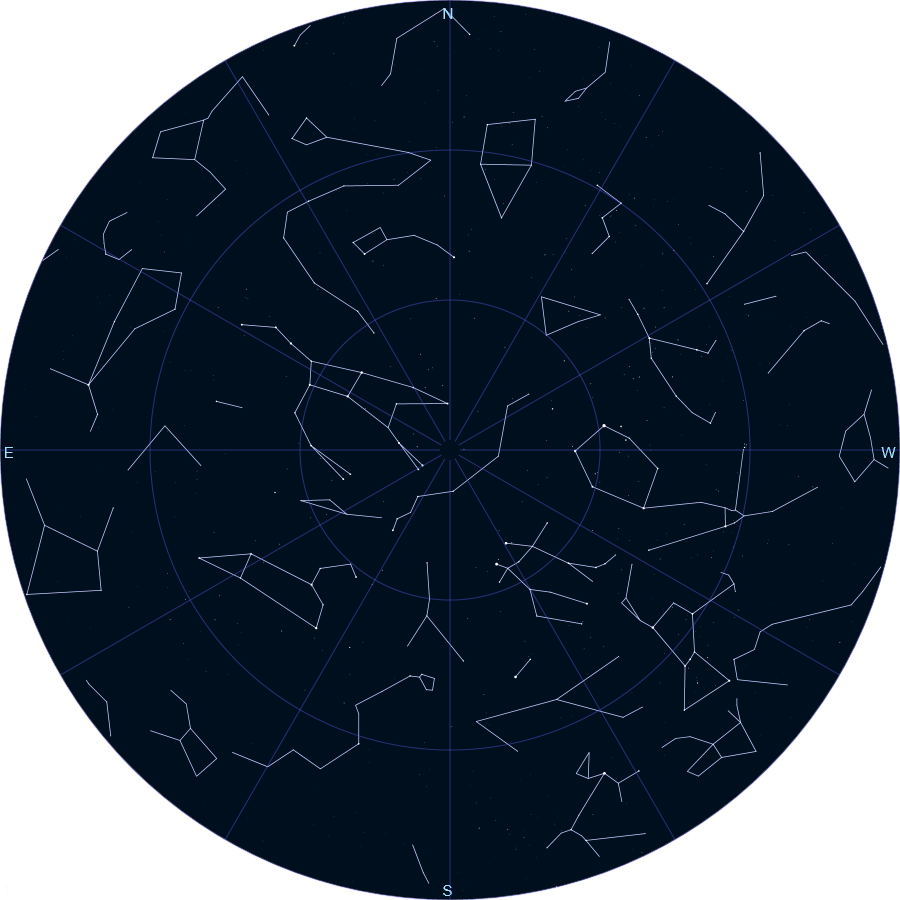

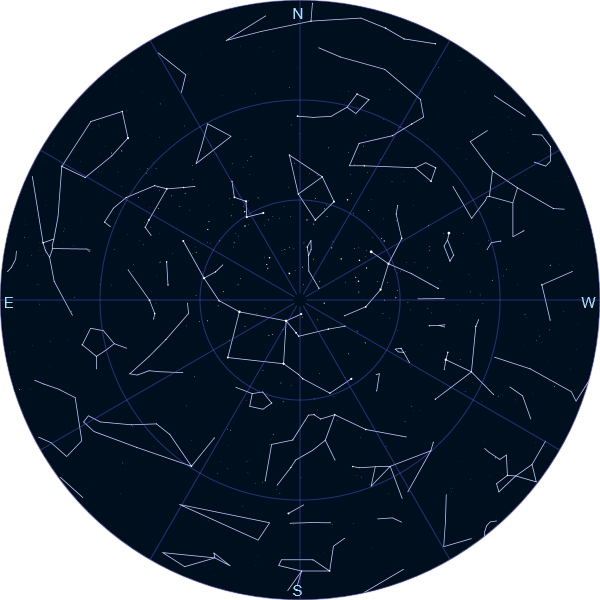

Greetings, fellow SkyWatchers! The week starts off with new Moon and the perfect opportunity to do a Messier Marathon. The planets continue to dazzle as we not only celebrate the Vernal Equinox, but the March Geminid meteor shower as well! If that doesn’t get your pulsar racing – nothing will. It’s time to get out your binoculars and telescopes and meet me in the backyard!

Monday, March 19 – Right now the Moon is between the Earth and the Sun, and you know what that means…New Moon! Tonight we’ll start in northern Puppis and collect three more Herschel studies as we begin at Alpha Monoceros and drop about four fingerwidths southeast to 19 Puppis.

NGC 2539 (Right Ascension: 8 : 10.7 – Declination: -12 : 50) averages around 6th magnitude and is a great catch for binoculars as an elongated hazy patch with 19 Puppis on the south side. Telescopes will begin resolution on its 65 compressed members, as well as split 19 Puppis – a wide triple. Shift about 5 degrees southwest and you find NGC 2479 (Right Ascension: 7 : 55.1 – Declination: -17 : 43) directly between two finderscope stars. At magnitude 9.6 it is telescopic only and will show as a smallish area of faint stars at low power. Head another degree or so southeast and you’ll encounter NGC 2509 (Right Ascension: 8 : 00.7 – Declination: -19 : 04) – a fairly large collection of around 40 stars that can be spotted in binoculars and small telescopes.

Tuesday, March 20 – Today is Vernal Equinox, one of the two times of the year that day and night become equal in length. From this point forward, the days will become longer – and our astronomy nights shorter! To the ancients, this was a time a renewal and planting – led by the goddess Eostre. As legend has it, she saved a bird whose wings were frozen from the winter’s cold, turning it into a hare which could also lay eggs. What a way to usher in the northern spring!

With the Moon still out of the picture, let’s finish our study of the Herschel objects in Puppis. Only three remain, and we’ll begin by dropping south-southeast of Rho and center the finder on a small collection of stars to locate NGC 2489 (Right Ascension: 7 : 56.2 – Declination: -30 : 04). At magnitude 7, this bright collection is worthy of binoculars, but only the small patch of stars in the center is the cluster. Under aperture and magnification you’ll find it to be a loose collection of around two dozen stars formed in interesting chains.

The next are a north-south oriented pair around 4 degrees due east of NGC 2489. You’ll find the northernmost – NGC 2571 (Right Ascension: 8 : 18.9 – Declination: -29 : 44) – at the northeast corner of a small finderscope or binocular triangle of faint stars. At magnitude 7, it will show as a fairly bright hazy spot with a few stars beginning to resolve with around 30 mixed magnitude members revealed to aperture. Less than a degree south is NGC 2567 (Right Ascension: 8 : 18.6 – Declination: -30 : 38). At around a half magnitude less in brightness, this rich open cluster has around 50 members to offer the larger telescope, which are arranged in loops and chains.

Congratulations on completing these challenging objects!

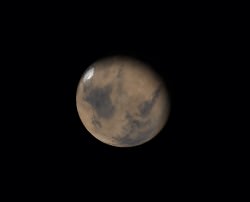

Are you up for another challenge? Then test your ability to judge magnitude as Mars has now dimmed to approximately -1.0. Does it look slightly different in size and brightness than it did a week or so ago? Keep watching!

Wednesday, March 21 – Take your telescopes or binoculars out tonight to look just north of Xi Puppis for a celebration of starlight known as M93 (Right Ascension: 7 : 44.6 – Declination: -23 : 52). Discovered in March of 1781 by Charles Messier, this bright open cluster is a rich concentration of various magnitudes that will simply explode in sprays of stellar fireworks in the eyepiece of a large telescope. Spanning 18 light-years of space and residing more than 3400 light-years away, it contains not only blue giants, but lovely golds as well. Jewels in the night…

Thursday, March 22 – Today in 1799 Friedrich Argelander was born. He was a compiler of star catalogues, studied variable stars and created the first international astronomical organization.

Tonight let’s celebrate no Moon and have a look at an object from an alternative catalog that was written by Lacaille, and which is about two fingerwidths south of Eta Canis Majoris.

Also known as Collinder 140, Lacaille’s 1751 catalog II.2 “nebulous star cluster” is a real beauty for binoculars and very low power in telescopes. More than 50% larger than the Full Moon, it contains around 30 stars and may be as far as 1000 light-years away. When re-cataloged by Collinder in 1931, its age was determined to be around 22 million years. While Lacaille noted it as nebulous, he was using a 15mm aperture reflector, and it is doubtful that he was able to fully resolve this splendid object. For telescope users, be sure to look for easy double Dunlop 47 in the same field.

Now, kick back and enjoy a spring evening with two meteor showers. In the northern hemisphere, look for the Camelopardalids. They have no definite peak, and a screaming fall rate of only one per hour. While that’s not much, at least they are the slowest meteors – entering our atmosphere at speeds of only 7 kilometers per second!

Far more interesting to both hemispheres will be the March Geminids which peak tonight. They were first discovered and recorded in 1973 and then confirmed in 1975. With a much faster fall rate of about 40 per hour, these slower than normal meteors will be fun to watch! When you see a bright streak, trace it back to its point of origin. Did you see a Camelopardalid, or a March Geminid?

Friday, March 23 – Today in 1840, the first photograph of the Moon was taken. The daguerreotype was exposed by American astronomer and medical doctor J. W. Draper. Draper’s fascination with chemical responses to light also led him to another first – a photo of the Orion Nebula.

Our target for tonight is an object that’s better suited for southern declinations – NGC 2451 (Right Ascension: 7 : 45.4 – Declination: -37 : 58). As both a Caldwell object (Collinder 161) and a southern skies binocular challenge, this colorful 2.8 magnitude cluster was probably discovered by Hodierna. Consisting of about 40 stars, its age is believed to be around 36 million years. It is very close to us at a distance of only 850 light-years. Take the time to closely study this object – for it is believed that due to the thinness of the galactic disk in this region, we are seeing two clusters superimposed on each other.

With the Moon out of the picture early, why not get caught up in a galaxy cluster study – Abell 426. Located just 2 degrees east of Algol in Perseus, this group of 233 galaxies spread over a region of several degrees of sky is easy enough to find – but difficult to observe. Spotting Abell galaxies in Perseus can be tough in smaller instruments, but those with large aperture scopes will find it worthy of time and attention.

At magnitude 11.6, NGC 1275 (Right Ascension: 3 : 19.8 – Declination: +41 : 31) is the brightest of the group and lies physically near the core of the cluster. Glimpsed in scopes as small as 150 mm aperture, NGC 1275 is a strong radio source and an active site of rapid star formation. Images of the galaxy show a strange blend of a perfect spiral being shattered by mottled turbulence. For this reason NGC 1275 is thought to be two galaxies in collision. Depending on seeing conditions and aperture, galaxy cluster Abell 426 may reveal anywhere from 10 to 24 small galaxies as faint as magnitude 15. The core of the cluster is more than 200 million light-years away, so it’s an achievement to spot even a few!

Saturday, March 24 – Today is the birthday of Walter Baade. Born in 1893, Baade was the first to resolve the Andromeda galaxy’s individual stars using the Hooker telescope during World War II blackout times, and he also developed the concept of stellar populations. He was the first to realize that there were two types of Cepheid variables, thereby refining the cosmic distance scale. He is also well known for discovering an area towards our galactic center which is relatively free of dust, now known as “Baade’s Window.”

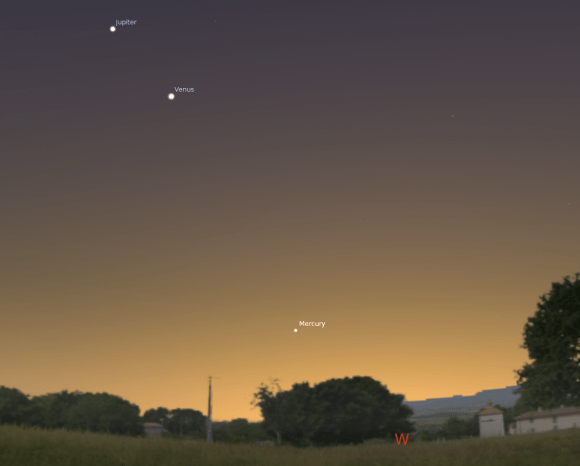

Just after sunset, you really need to take a look out your western window for a really beautiful bit of scenery. As the sky darkens, look for the very tender crescent Moon lit with “Earthshine”. Above it you will see bright Jupiter. Above that you will see blazing Venus. And, if that’s not enough, just a little higher will bring you to the Pleiades! What a great way to start a weekend evening!

With the Moon so near the horizon, we have only a short time to view its features. Tonight let’s start with a central feature – Langrenus – and continue further south for crater Vendelinus. Spanning 92 by 100 miles and dropping 14,700 feet below the lunar surface, Vendelinus displays a partially dark floor with a west wall crest catching the brilliant light of an early sunrise. Notice also that its northeast wall is broken by a younger crater – Lame. Head’s up! It’s an Astronomical League challenge.

Once the Moon has set, revisit M46 in Puppis – along with its mysterious planetary nebula NGC 2438. Follow up with a visit to neighboring open cluster M47 – two degrees west-northwest. M47 may actually seem quite familiar to you already. Did you possibly encounter it when originally looking for M46? If so, then it’s also possible that you met up with 6.7 magnitude open cluster NGC 2423 (Right Ascension: 7 : 37.1 – Declination: -13 : 52), about a degree northeast of M47 and even dimmer 7.9 magnitude NGC 2414 (Right Ascension: 7 : 33.3 – Declination: -15 : 27 ) as well. That’s four open clusters and a planetary nebula all within four square arc-minutes of sky. That makes this a cluster of clusters!

Let’s return to study M47. Observers with binoculars or using a finderscope will notice how much brighter, and fewer, the stars of M47 are when compared to M46. This 12 light-year diameter compact cluster is only 1600 light-years away. Even as close as it is, not more than 50 member stars have been identified. M47 has about one tenth the stellar population of larger, denser, and three times more distant, M46.

Of historical interest, M47 was “discovered” three times: first by Giovanni Batista Hodierna in the mid-17th century, then by Charles Messier some 17 years later, and finally by William Herschel 14 years after that. How is it possible that such a bright and well-placed cluster needed “re-discovery?” Hodierna’s book of observations didn’t surface until 1984, and Messier gave the cluster’s declination the wrong sign, making its identification an enigma to later observers – because no such cluster could be found where Messier said it was!

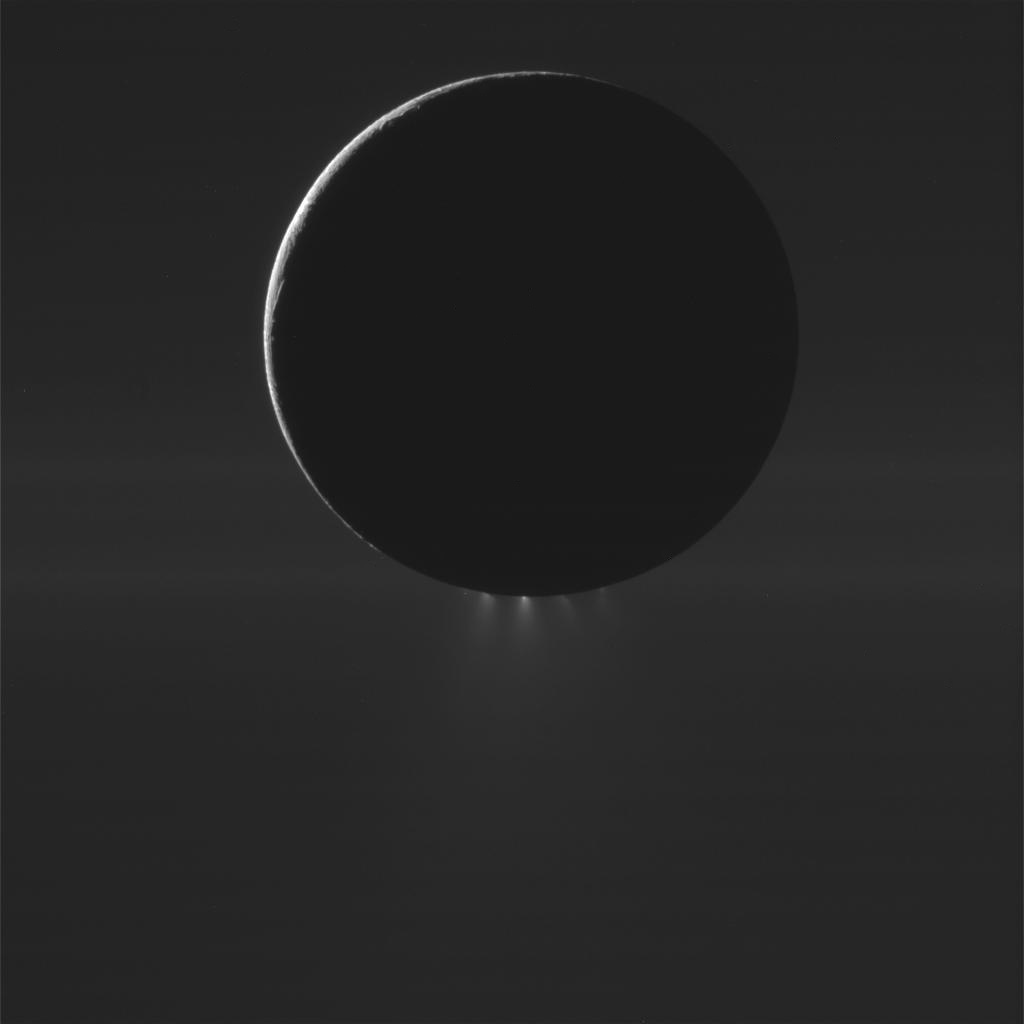

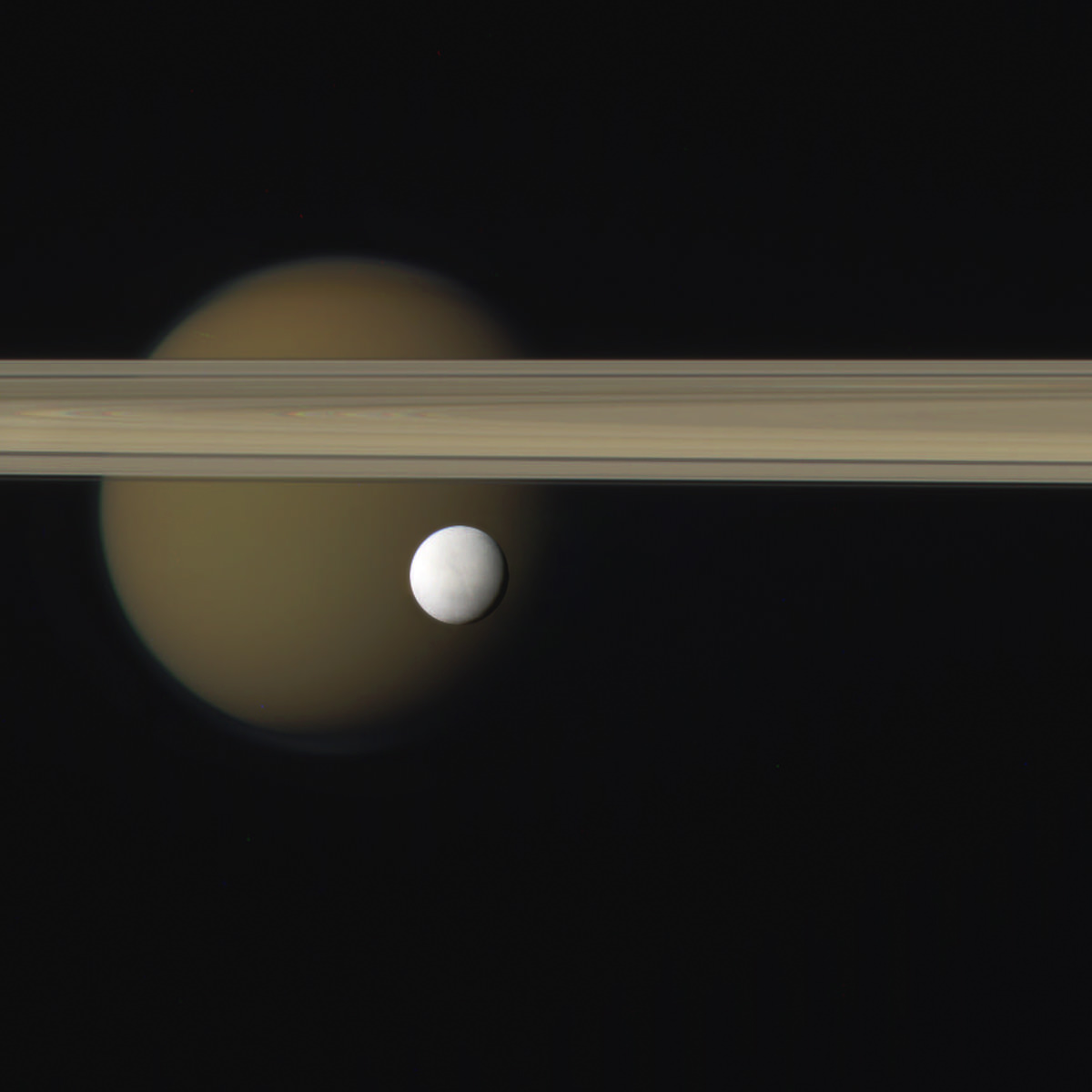

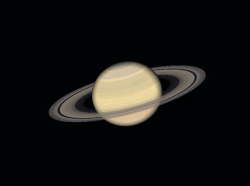

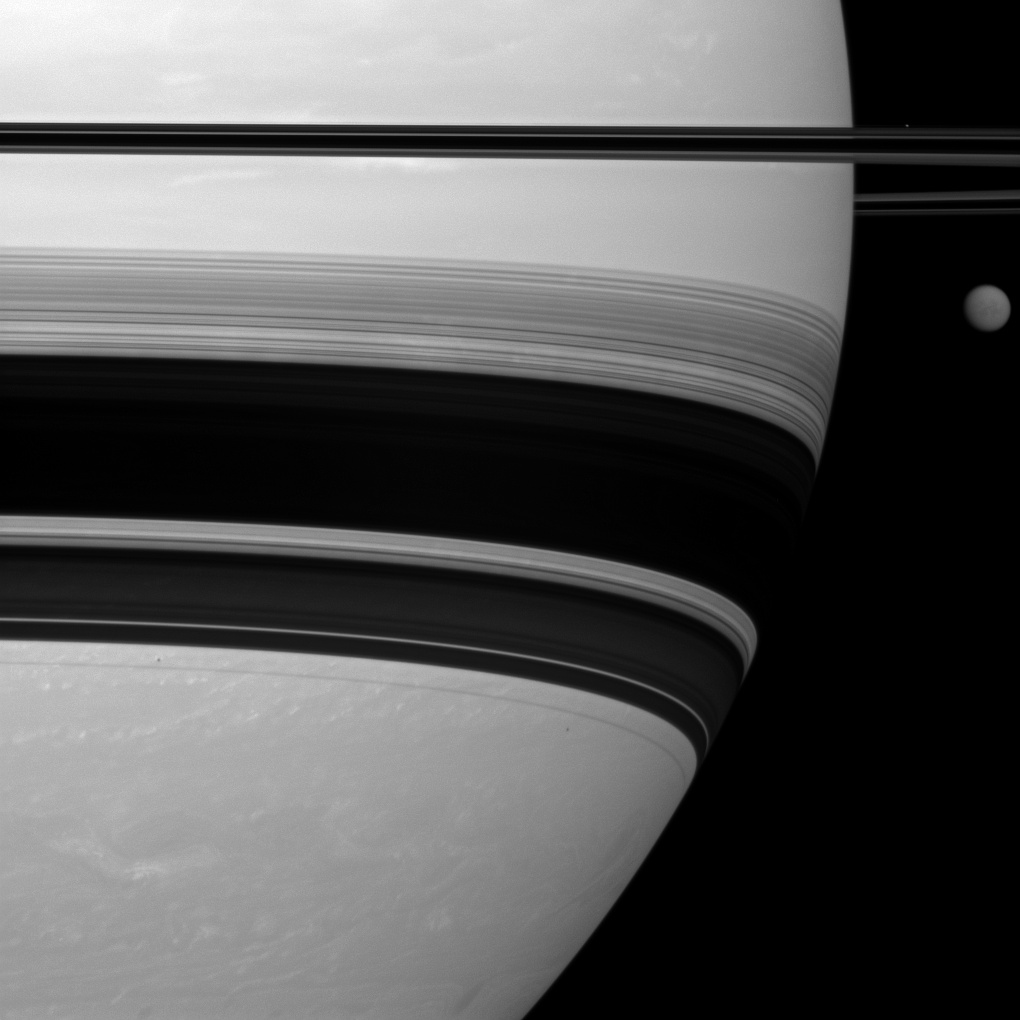

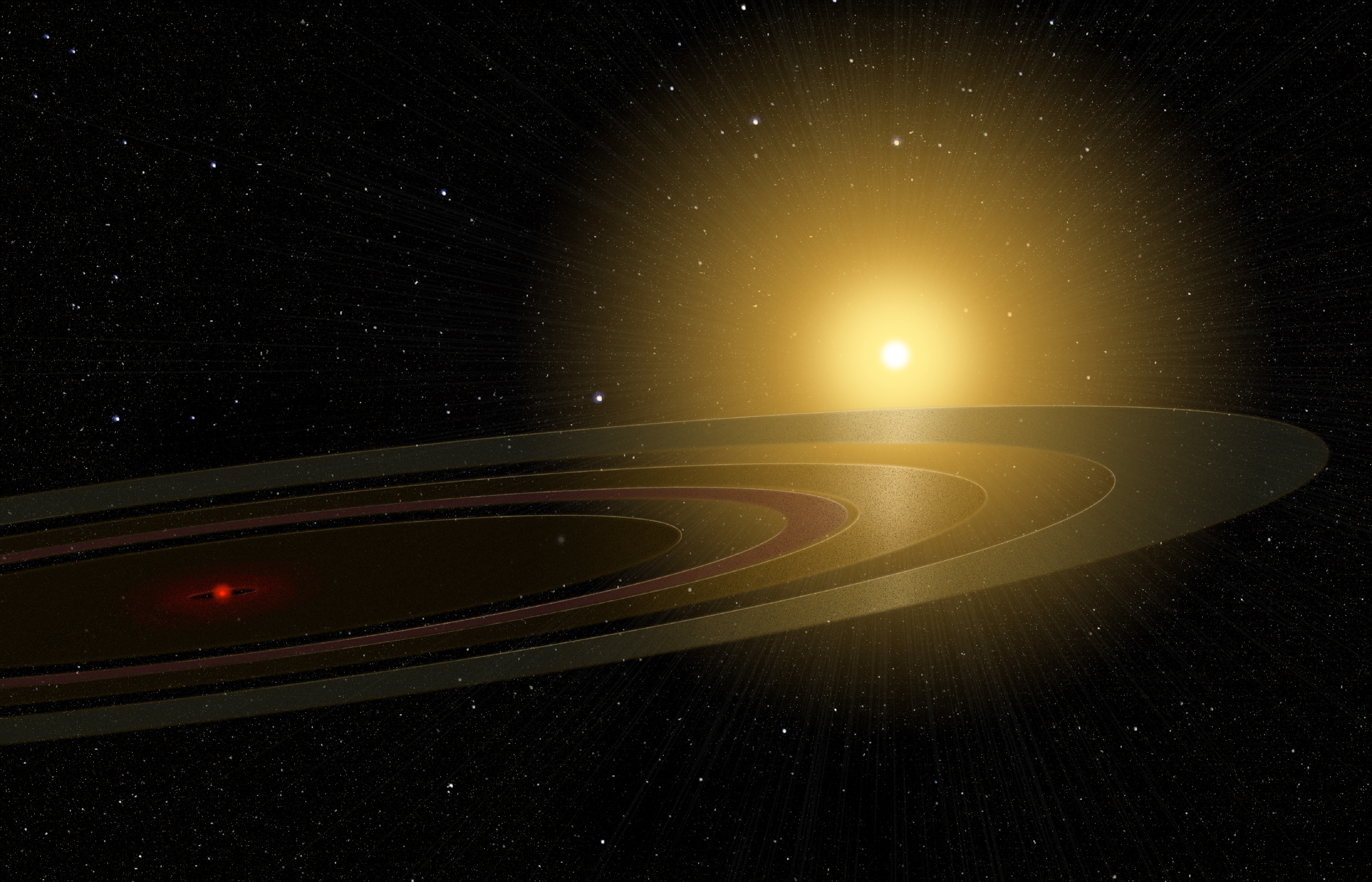

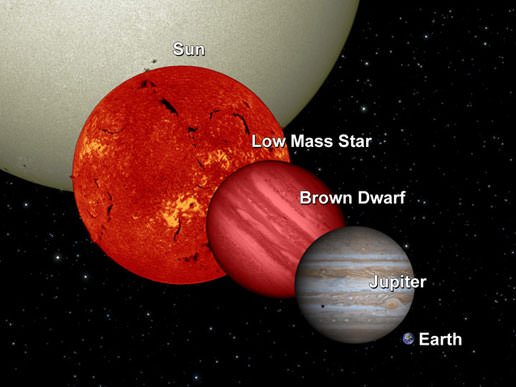

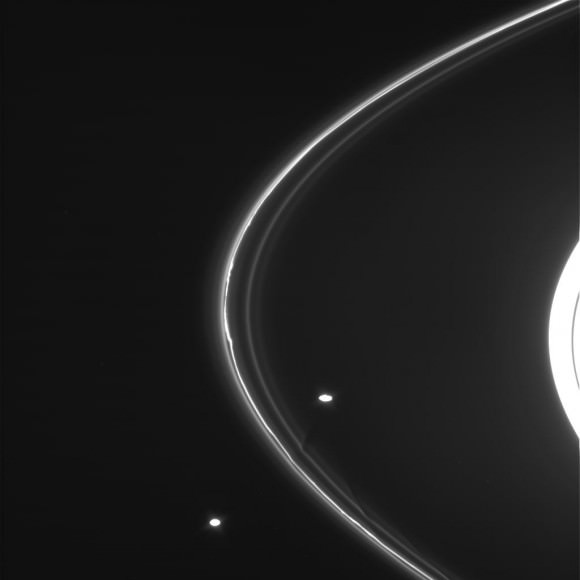

Sunday, March 25 – Today in 1655, Titan – Saturn’s largest satellite – was discovered by Christian Huygens. He also discovered Saturn’s ring system during this same year. 350 years later, the probe named for Huygens stunned the world as it reached Titan and sent back information on this distant world. How about if we visit Saturn? You’ll find the creamy yellow planet located about a fistwidth northwest of bright, white Spica! Even a small telescope will reveal Titan, but remember… it orbits well outside the ring plane, so don’t mistake it for a background star! While you’re there, look closely around the ring edges for the smaller moons. A 4.5” telescope can easily show you three of them. How about the shadow the rings on the planet’s surface? Or how about the shadow of the planet on the rings? Is the Cassini division visible? If you have a larger telescope, look for other ring divisions as well. All are part and parcel of viewing incredible Saturn!

If you missed yesterday evening’s scenic line-up, don’t despair. Just after the Sun sets tonight – and above the western horizon – you’ll find the young Moon very closely paired with Jupiter. Keep traveling eastward (up) and you’ll encounter Venus. Continue east and the next stop is M45. Watch in the days ahead as the Moon sweeps by, continuing to provide us with a show! Need more? Then check out Leo and Mars! You’ll find a great triangulation of Regulus to the west, Mars to the east and Algieba to the north. If you didn’t know better, you’d almost swear the Lion swallowed the red planet.

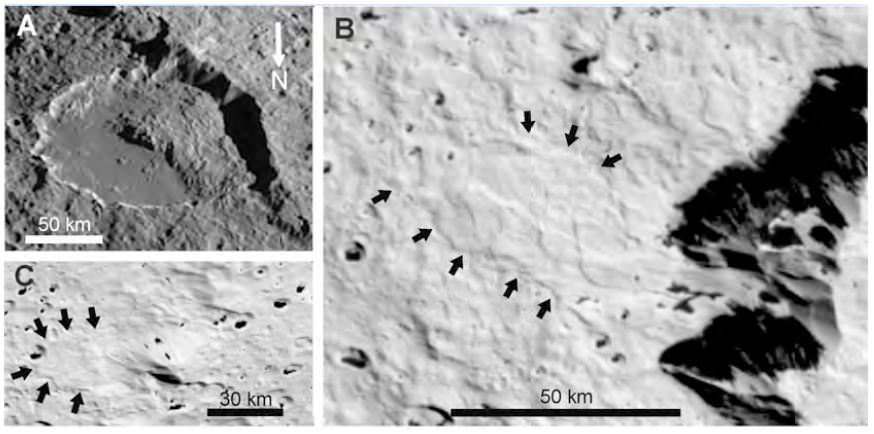

Tonight let’s return to our previous studies of the Moon and revisit a challenging crater. Further south than Vendelinus, look for another large, mountain-walled plain named Furnerius, located not too far from the terminator. Although it has no central peak, its walls have been broken numerous times by many smaller impacts. Look at a rather large one just north of central on the crater floor. If skies are stable, power up and search for a rima extending from the northern edge. Keep in mind as you observe that our own Earth has been pummeled just as badly as its satellite.

On this day in 1951, 21 cm wavelength radiation from atomic hydrogen in the Milky Way was first detected. 1420 MHz H I studies continue to form the basis of a major part of modern radio astronomy. If you would like to have a look at a source of radio waves known as a pulsar, then aim your binoculars slightly more than a fistwidth east of bright Procyon. The first two bright stars you encounter will belong to the constellation of Hydrus and you will find pulsar CP0 834 just above the northernmost – Delta.

Unitl next week? May all your journeys be at light speed!