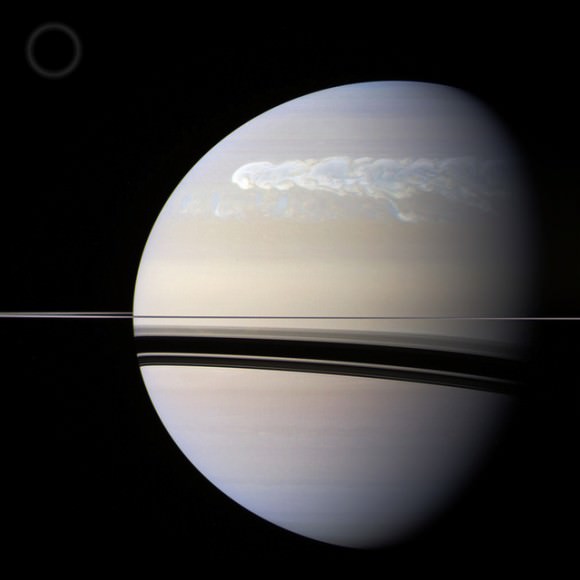

[/caption]

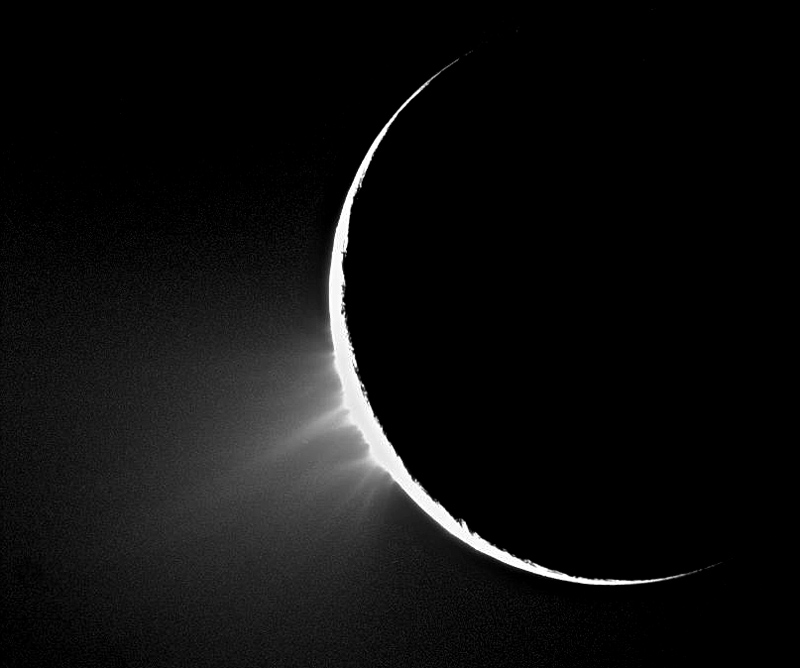

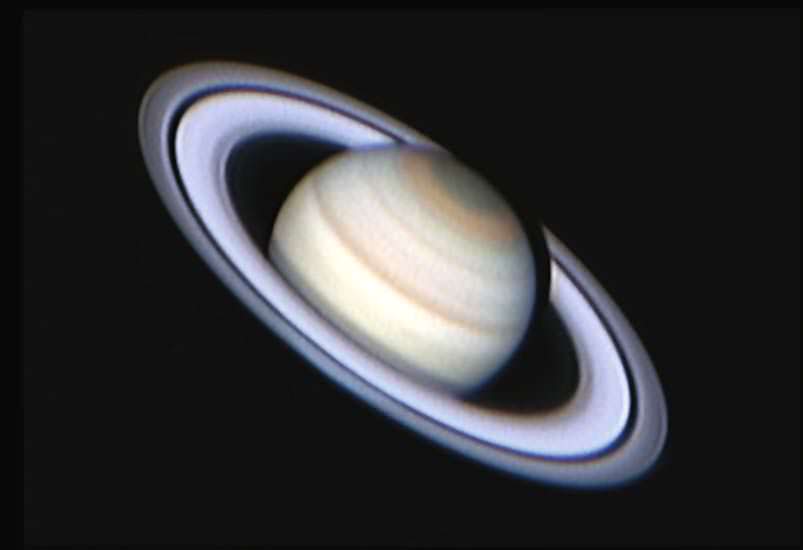

Researchers on the Cassini mission team have identified large salt grains in the plumes emanating from Saturn’s icy satellite Enceladus, making an even stronger case for the existence of a salty liquid ocean beneath the moon’s frozen surface.

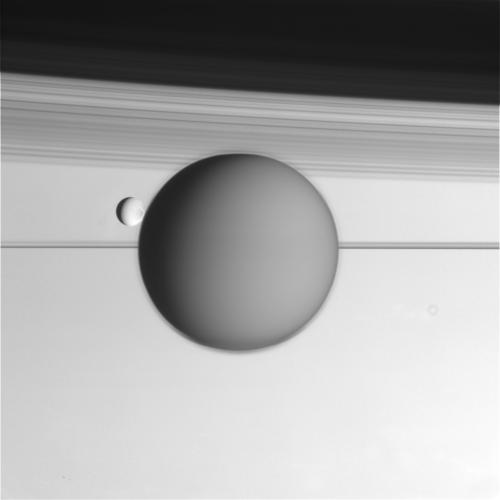

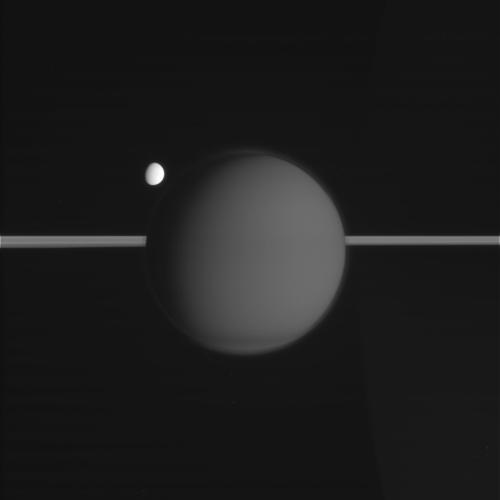

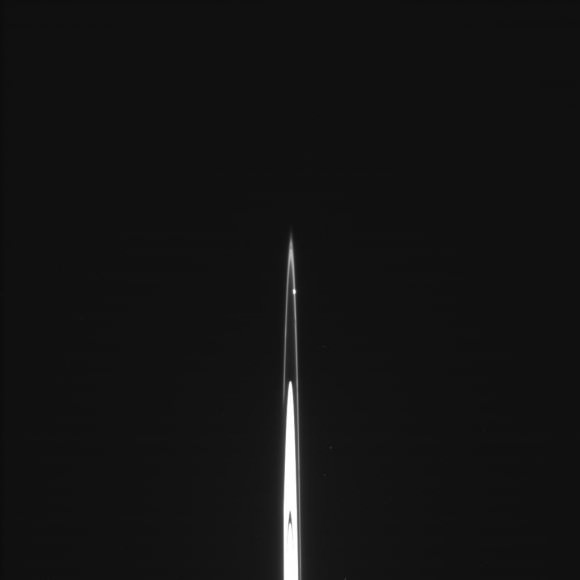

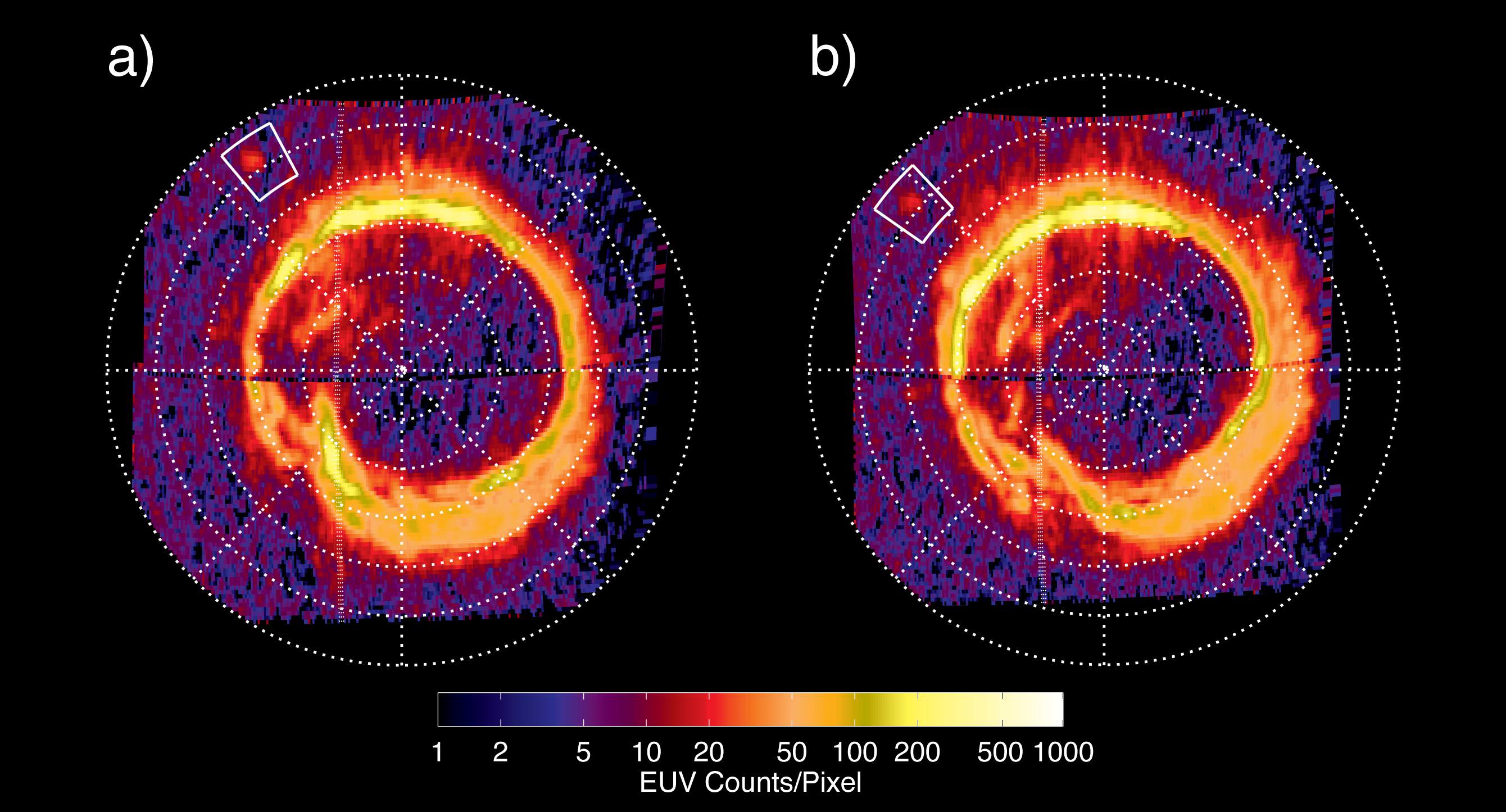

Cassini first discovered the jets of water ice particles in 2005; since then scientists have been trying to learn more about how they behave, what they are made of and – most importantly – where they are coming from. The running theory is that Enceladus has a liquid subsurface ocean of as-of-yet undetermined depth and volume, and pressure from the rock and ice layers above combined with heat from within force the water up through surface cracks near the moon’s south pole. When this water reaches the surface it instantly freezes, sending plumes of ice particles hundreds of miles into space.

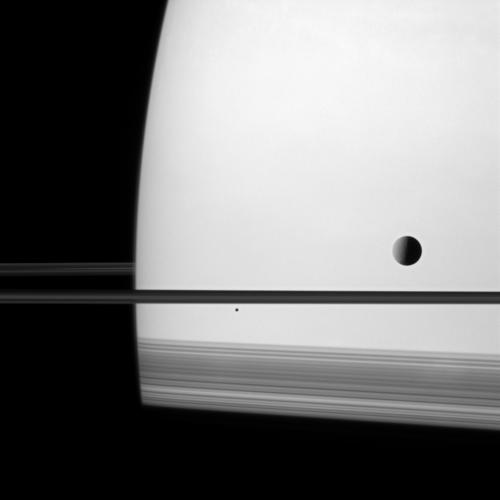

Much of the ice ends up in orbit around Saturn, creating the hazy E ring in which Enceladus resides.

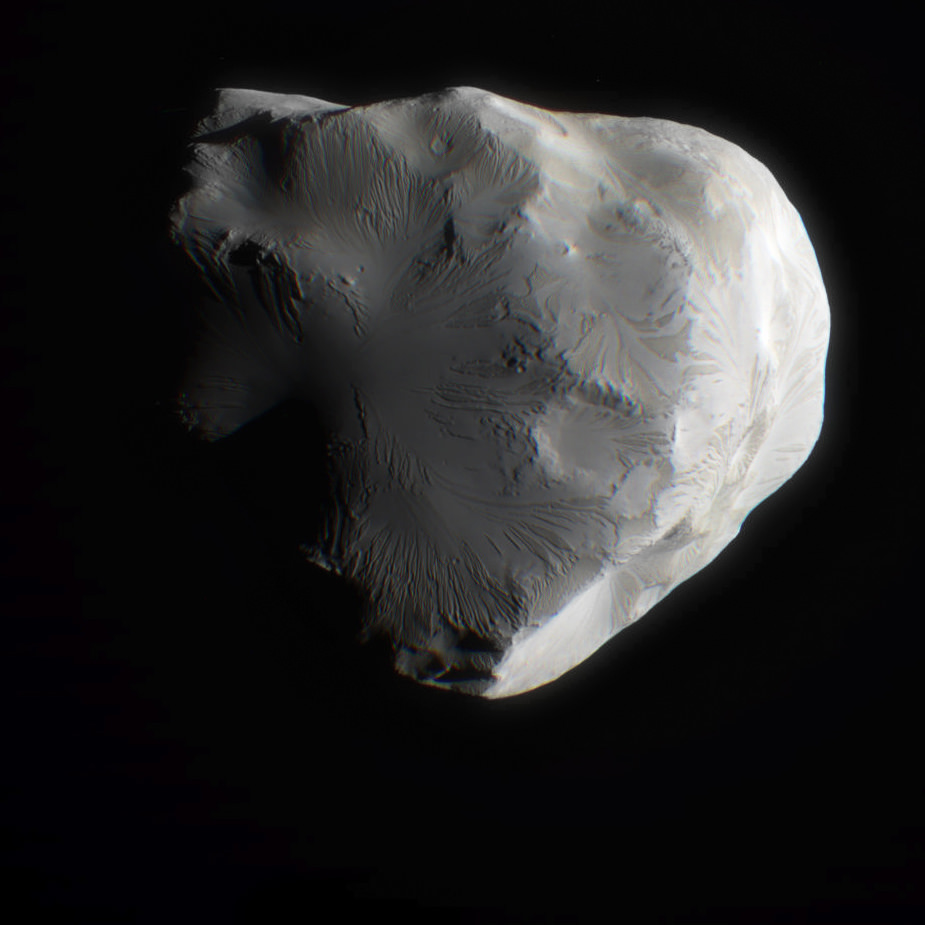

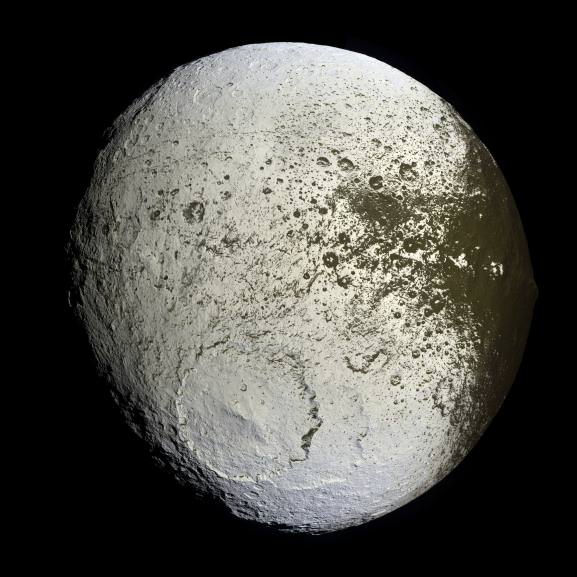

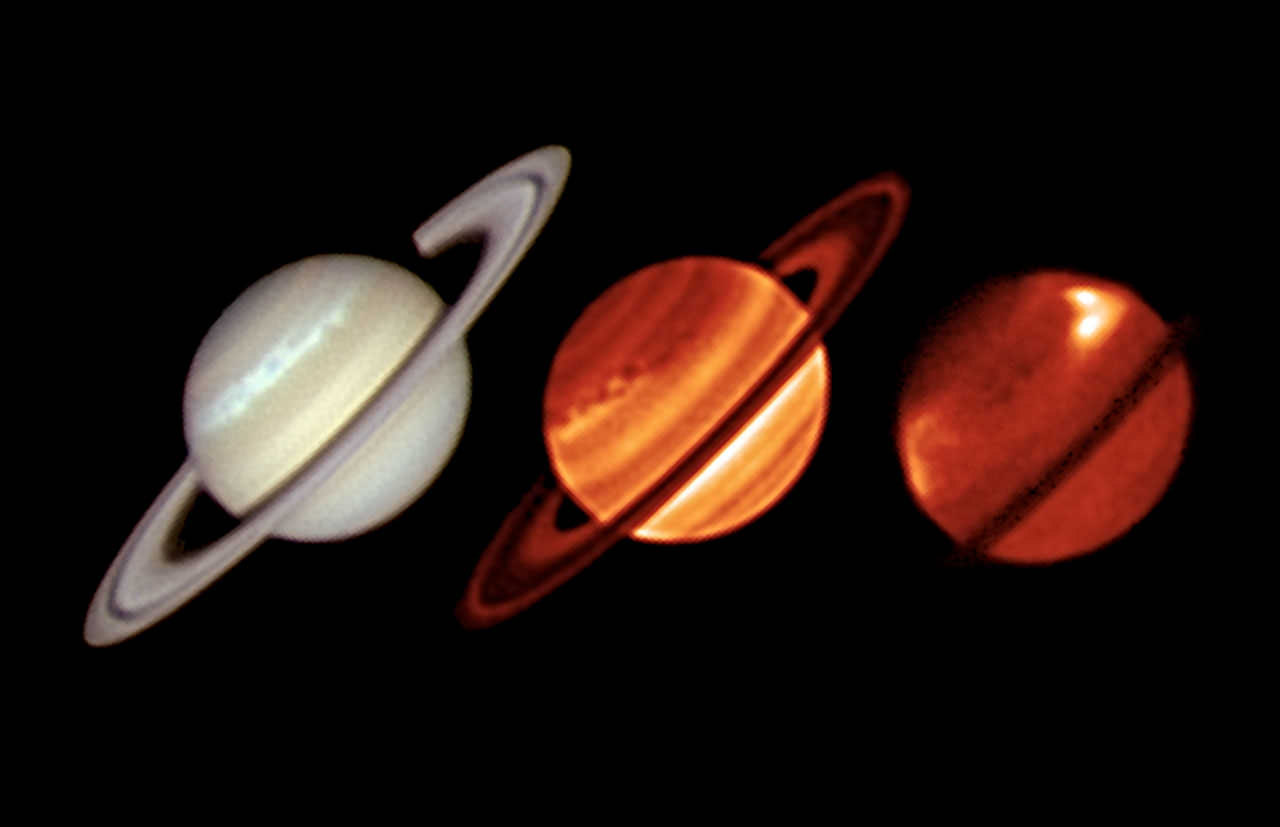

Although the discovery of the plumes initially came as a surprise, it’s the growing possibility of liquid water that’s really intriguing – especially that far out in the Solar System and on a little 504-km-wide moon barely the width of Arizona. What’s keeping Enceladus’ water from freezing as hard as rock? It could be tidal forces from Saturn, it could be internal heat from its core, a combination of both – or something else entirely… astronomers are still hard at work on this mystery.

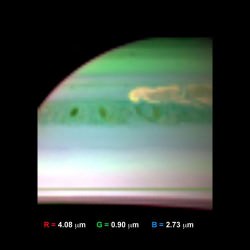

Now, using data obtained from flybys in 2008 and 2009 during which Cassini flew directly through the plumes, researchers have found that the particles in the jets closest to the moon contain large sodium- and potassium-rich salt grains. This is the best evidence yet of the existence of liquid salt water inside Enceladus – a salty underground ocean.

“There currently is no plausible way to produce a steady outflow of salt-rich grains from solid ice across all the tiger stripes other than salt water under Enceladus’s icy surface.”

– Frank Postberg, Cassini team scientist, University of Heidelberg, Germany

If there indeed is a reservoir of liquid water, it must be pretty extensive since the numerous plumes are constantly spraying water vapor at a rate of 200 kg (400 pounds) every second – and at several times the speed of sound! The plumes are ejected from points within long, deep fissures that slash across Enceladus’ south pole, dubbed “tiger stripes”.

Recently the tiger stripe region has also been found to be emanating a surprising amount of heat, even further supporting a liquid water interior – as well as an internal source of energy. And where there’s liquid water, heat energy and organic chemicals – all of which seem to exist on Enceladus – there’s also a case for the existence of life.

“This finding is a crucial new piece of evidence showing that environmental conditions favorable to the emergence of life can be sustained on icy bodies orbiting gas giant planets.”

– Nicolas Altobelli, ESA project scientist for Cassini

Enceladus has intrigued scientists for many years, and every time Cassini takes a closer look some new bit of information is revealed… we can only imagine what other secrets this little world may hold. Thankfully Cassini is going strong and more than happy to keep on investigating!

“Without an orbiter like Cassini to fly close to Saturn and its moons — to taste salt and feel the bombardment of ice grains — scientists would never have known how interesting these outer solar system worlds are.”

– Linda Spilker, Cassini project scientist at JPL

The findings were published in this week’s issue of the journal Nature.

Read more in the NASA press release here.

Image credits: NASA / JPL / Space Science Institute

__________________

Jason Major is a graphic designer, photo enthusiast and space blogger. Visit his website Lights in the Dark and follow him on Twitter @JPMajor or on Facebook for the most up-to-date astronomy awesomeness!