[/caption]

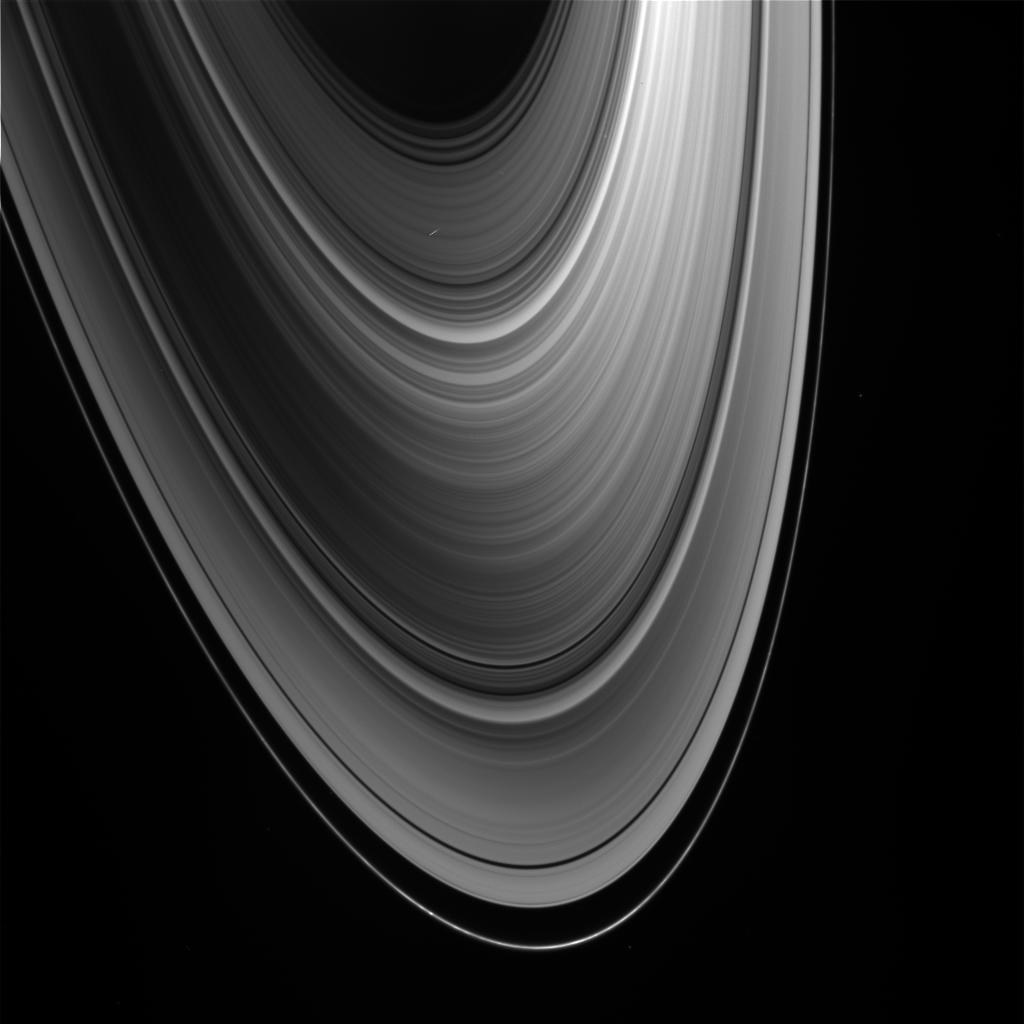

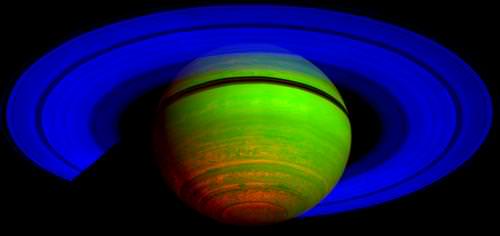

The formation of Saturn’s rings has been one of the classical if not eternal questions in astronomy. But one researcher has provided a provocative new theory to answer that question. Robin Canup from the Southwest Research Institute has uncovered evidence that the rings came from a large, Titan-sized moon that was destroyed as it spiraled into a young Saturn.

Over the years, different theories have evolved on how the rings formed around Saturn. The two leading theories involve a small moon that was shattered by meteor impacts, or the tidal disruption of a comet coming too close to Saturn.

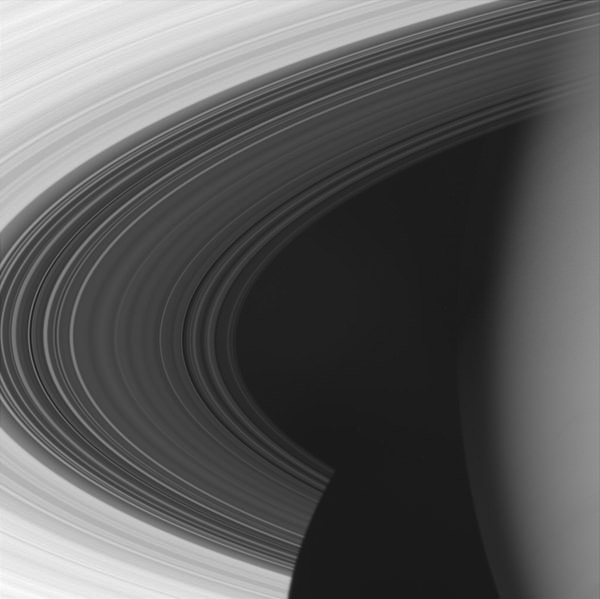

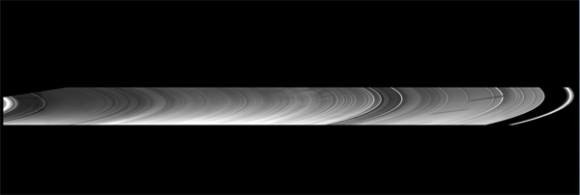

But Saturn’s main rings are about 90% water ice by mass, and because bombardment of the rings by micrometeoroids increases their rock content over time, Canup said the rings’ current composition implies that they were essentially pure ice when they formed.

However, disruption of a small moon would generally lead to a mixed rock-ice ring, while tidal disruptions of comets would occur much more often at Jupiter, Uranus and Neptune than at Saturn.

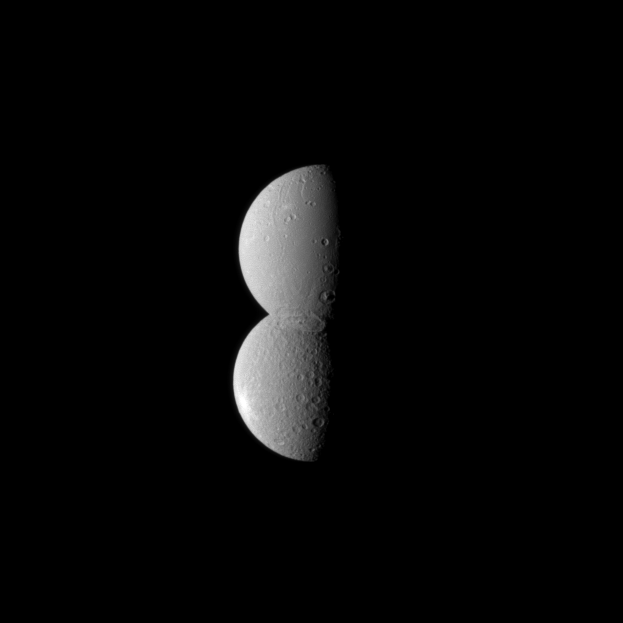

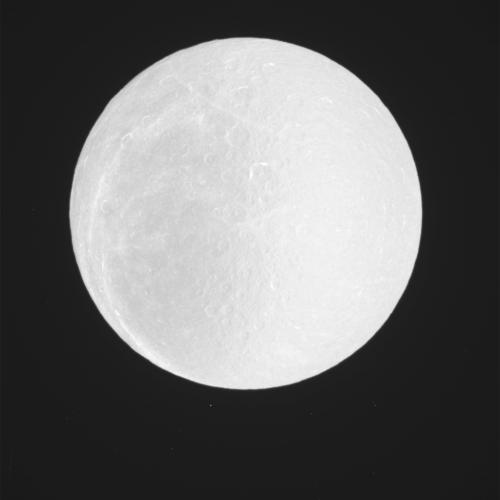

Additionally, neither of these theories would explain Saturn’s inner moons, which have low enough densities that they too must be comprised of nearly pure ice.

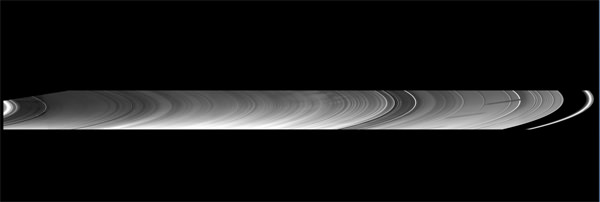

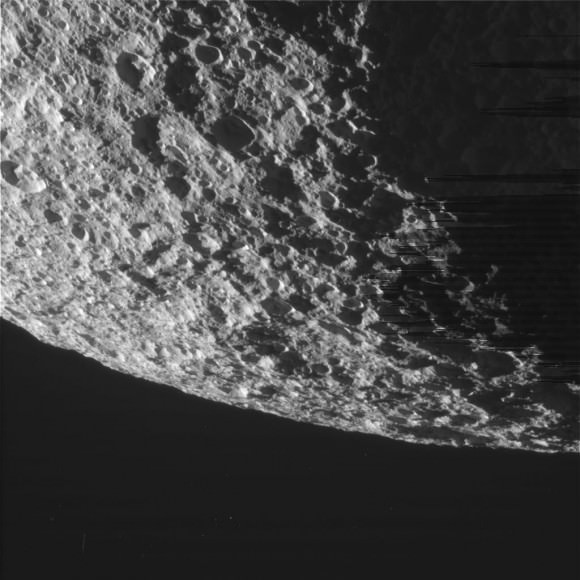

Canup’s new alternative theory is that Titan-sized moon with a rocky core and an icy mantle spiraled into Saturn early in solar system history. Tidal forces ripped off part of the icy mantle, distributing it into what would become the rings. But the rocky core was made of more durable material that held together until it hit Saturn’s surface. “The end result is a pure ice ring,” Canup said in an article in Nature.

Over time the ring spreads out and its mass decreases, and icy moons are created. Due to changes in the evolving Saturn system, these “spawned” moons then spiraled outward rather than inward. In this way, ice rings and ice-enhanced inner moons originate as a primordial byproduct of the same process that produces Saturn’s regular satellite system, making the whole process simpler than if there were several events.

Canup studies formation events with detailed computer simulations, including studying how our own Moon formed.

She presented her findings at the American Astronomical Society’s Division for Planetary Science meeting this week, in Pasadena, California, and her presentation was detailed in an article in Nature.

Sources: Canup’s abstract, Nature