This photograph, captured by NASA’s Cassini spacecraft shows Saturn’s moons Enceladus and Janus. Also visible is Saturn’s F ring, including the bright core which is about 50 km wide, and contains many features of its own. Cassini took this photograph on May 21, 2006 when it was approximately 565,000 kilometers (351,000 miles) from Janus and 702,000 kilometers (436,000 miles) from Enceladus.

Continue reading “Enceladus and Janus”

Enceladus Passes Before Titan

This natural colour photograph from Cassini shows Saturn’s moon Enceladus passing in front of Titan. With this colour view, it’s easy to see how different these two moons are. Titan has its golden, smoggy atmosphere, while Enceladus is mostly gray, darkened ice. Cassini took this image on February 5, 2006 when it was 4.1 million kilometers (2.5 million miles) from Enceladus.

Continue reading “Enceladus Passes Before Titan”

Dione Passes in Front of Rhea

This photograph, captured by NASA’s Cassini spacecraft, shows Saturn’s moon Dione crossing the face of Rhea. Dione is on the right, and it’s about two-thirds the size of Rhea, and it has a much smoother surface, suggesting it has been modified more recently. The image was taken on May 14, 2006 at a distance of approximately 2.7 million kilometers (1.7 million miles) from Dione.

Continue reading “Dione Passes in Front of Rhea”

Crescent Moon Dione

This photograph shows Saturn’s moon Dione as a thin crescent beneath the luminous F ring. The image shows the dark side of the rings, so they’re not illuminated directly by the Sun. Cassini took this photo on May 3, 2006 at a distance of approximately 1.8 million kilometers (1.1 million miles) from Dione.

Continue reading “Crescent Moon Dione”

Gas Giants Gobbled Up Most of Their Moons

Even though our Solar System’s gas giants vary widely in size and mass, they do have something in common. Each planet is roughly 10,000 times more massive than the combined mass of all their moons. During planetary formation, rocky moons grew out of the solid material surrounding each planet. As these moons grew larger, leftover gas slowed them down, and they fell into the planet to be consumed. The moons we see today were the last ones to form around their parent planets, after the gas had dissipated.

Continue reading “Gas Giants Gobbled Up Most of Their Moons”

Strange Cloud Features on Saturn

This close up view of Saturn shows an unusual feature in its atmosphere. It appears as if part of one belt is crossing over into another. Another possibility is that it’s just an illusion created by different layers of clouds. Cassini took this photograph on May 12, 2006 at a distance of approximately 2.9 million kilometers (1.8 million miles) from Saturn.

Continue reading “Strange Cloud Features on Saturn”

Icy Tail on Enceladus

A plume of water ice is seen streaming off the southern pole of Saturn’s moon Enceladus in this photograph. Cassini used very long exposure to capture the wispy stream of vapour, so everything else in the image is overexposed. Cassini took the photograph on May 4, 2006 at a distance of approximately 2.1 million kilometers (1.3 million miles) from Enceladus.

Continue reading “Icy Tail on Enceladus”

Titan Behind Saturn and the Rings

This photograph shows Titan partly obscured behind Saturn and its rings. The image was taken from above the ringplane, and shows the side of the planet unlit by the Sun. Cassini captured this view on May 10, 2006 at a distance of approximately 2.9 million kilometers (1.8 million miles) from Saturn.

Continue reading “Titan Behind Saturn and the Rings”

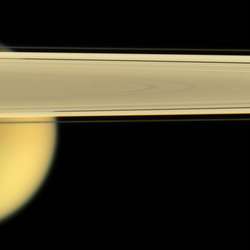

Titan Behind the Rings

Titan behind Saturn’s icy ring. Image credit: NASA/JPL/SSI Click to enlarge

Titan peeks from behind Saturns rings in this recent Cassini photograph. The dark Enke gap and narrow F-ring are visible. Cassini took this image on April 28, 2006 when it was approximately 1.8 million kilometers (1.1 million miles) from Titan.

Saturn’s largest moon, Titan, peaks out from under the planet’s rings of ice.

This view looks toward Titan (5,150 kilometers, or 3,200 miles across) from slightly beneath the ringplane. The dark Encke gap (325 kilometers, or 200 miles wide) is visible here, as is the narrow F ring.

Images taken using red, green and blue spectral filters were combined to create this natural color view. The images were taken with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on April 28, 2006 at a distance of approximately 1.8 million kilometers (1.1 million miles) from Titan. Image scale is 11 kilometers (7 miles) per pixel on Titan.

The Cassini-Huygens mission is a cooperative project of NASA, the European Space Agency and the Italian Space Agency. The Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a division of the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, manages the mission for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, Washington, D.C. The Cassini orbiter and its two onboard cameras were designed, developed and assembled at JPL. The imaging operations center is based at the Space Science Institute in Boulder, Colo.

For more information about the Cassini-Huygens mission visit http://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov . The Cassini imaging team homepage is at http://ciclops.org .

Original Source: NASA/JPL/SSI News Release

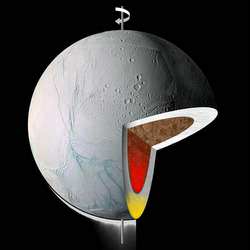

Saturn’s Moon Enceladus Rolled Over

An illustration of the interior of Saturn’s moon Enceladus. Image credit: NASA. Click to enlarge

Saturn’s moon Enceladus has a strange hot spot at its southern pole; a region that should be one of its coldest places. Scientists think that warm material inside the moon created an instability. The moon eventually rolled over, repositioning the spot at its southern pole. Other bodies in the Solar System, such as Uranus’ moon Miranda, have probably undergone similar rolls in the past.

Saturn’s moon Enceladus – an active, icy world with an unusually warm south pole ? may have performed an unusual trick for a planetary body. New research shows Enceladus rolled over, literally, explaining why the moon’s hottest spot is at the south pole.

Enceladus recently grabbed scientists’ attention when the Cassini spacecraft observed icy jets and plumes indicating active geysers spewing from the tiny moon’s south polar region.

“The mystery we set out to explain was how the hot spot could end up at the pole if it didn’t start there,” said Francis Nimmo, assistant professor of Earth sciences, University of California, Santa Cruz.

The researchers propose the reorientation of the moon was driven by warm, low-density material rising to the surface from within Enceladus. A similar process may have happened on Uranus’ moon Miranda, they said. Their findings are in this week’s journal Nature.

“It’s astounding that Cassini found a region of current geological activity on an icy moon that we would expect to be frigidly cold, especially down at this moon’s equivalent of Antarctica,” said Robert Pappalardo, co-author and planetary scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. “We think the moon rolled over to put a deeply seated warm, active area there.” Pappalardo worked on the study while at the University of Colorado.

Rotating bodies, including planets and moons, are stable if more of their mass is close to the equator. “Any redistribution of mass within the object can cause instability with respect to the axis of rotation. A reorientation will tend to position excess mass at the equator and areas of low density at the poles,” Nimmo said. This is precisely what happened to Enceladus.

Nimmo and Pappalardo calculated the effects of a low-density blob beneath the surface of Enceladus and showed it could cause the moon to roll over by up to 30-degrees and put the blob at the pole.

Pappalardo used an analogy to explain the Enceladus rollover. “A spinning bowling ball will tend to roll over to put its holes — the axis with the least mass — vertically along the spin axis. Similarly, Enceladus apparently rolled over to place the portion of the moon with the least mass along its vertical spin axis,” he said.

The rising blob (called a “diapir”) may be within either the icy shell or the underlying rocky core of Enceladus. In either case, as the material heats up it expands and becomes less dense, then rises toward the surface. This rising of warm, low-density material could also help explain the high heat and striking surface features, including the geysers and “tiger-stripe” region suggesting fault lines caused by tectonic stress.

Internal heating of Enceladus probably results from its eccentric orbit around Saturn. “Enceladus gets squeezed and stretched by tidal forces as it orbits Saturn, and that mechanical energy is transformed into heat energy in the moon’s interior,” added Nimmo.

Future Cassini observations of Enceladus may support this model. Meanwhile, scientists await the next Enceladus flyby in 2008 for more clues.

This research was supported by grants from NASA. The Cassini-Huygens mission is a cooperative project of NASA, the European Space Agency and the Italian Space Agency. JPL, a division of Caltech, manages the mission for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate. The Cassini orbiter was designed, developed and assembled at JPL.

For images and information about the Cassini mission, visit: http://www.nasa.gov/cassini and http://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov .

Original Source: NASA News Release