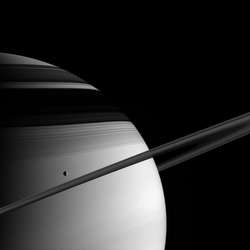

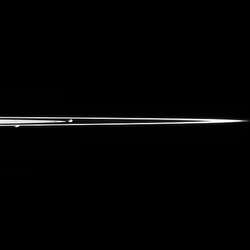

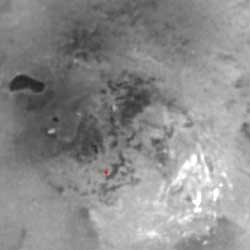

F ring appears against the planet and above Prometheus. Image credit: NASA/JPL/SSI. Click to enlarge

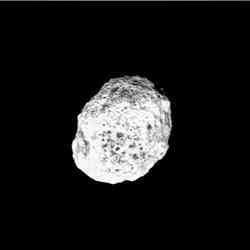

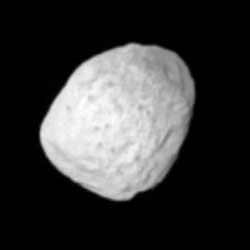

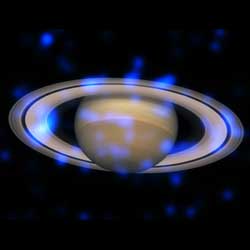

Cassini peers through the icy particles that comprise Saturn’s rings as Prometheus sits perched on the planet’s limb (edge). The rings cast shadows on the planet, with darker regions corresponding to places where the ring material is denser. The narrow dense regions are created by gravitational resonances with moons, like Prometheus, that orbit near the rings. Prometheus is 102 kilometers (63 miles) across.

The thin, bright core of the F ring can be seen against the planet and above Prometheus.

The image was taken in visible light with the Cassini spacecraft narrow-angle camera on June 3, 2005, at a distance of approximately 2.1 million kilometers (1.3 million miles) from Saturn. The image scale is 13 kilometers (8 miles) per pixel.

The Cassini-Huygens mission is a cooperative project of NASA, the European Space Agency and the Italian Space Agency. The Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a division of the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, manages the mission for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, Washington, D.C. The Cassini orbiter and its two onboard cameras were designed, developed and assembled at JPL. The imaging team is based at the Space Science Institute, Boulder, Colo.

For more information about the Cassini-Huygens mission visit http://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov . The Cassini imaging team homepage is at http://ciclops.org .

Original Source: NASA/JPL/SSI News Release