Every planet in the Solar System takes a certain amount of time to complete a single orbit around the Sun. Here on Earth, this period lasts 365.25 days – a period that we refer to as a year. When it comes to the other planets, we use this measurement to characterize their orbital periods. And what we have found is that on many of these planets, depending on their distance from the Sun, a year can last a very long time!

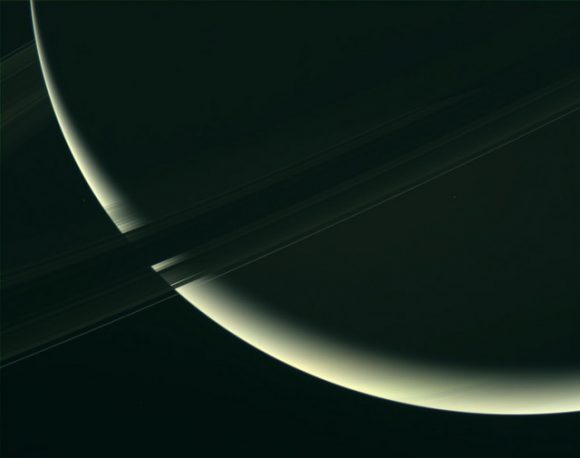

Consider Saturn, which orbits the Sun at a distance of about 9.5 AU – i.e. nine and a half times the distance between the Earth and the Sun. Because of this, the speed with which it orbits the Sun is also considerably slower. As a result, a single year on Saturn lasts an average of about twenty-nine and a half years. And during that time, some interesting changes happen for the planet’s weather systems.

Orbital Period:

Saturn orbits the Sun at an average distance (semi-major axis) of 1.429 billion km (887.9 million mi; 9.5549 AU). Because its orbit is elliptical – with an eccentricity of 0.05555 – its distance from the Sun ranges from 1.35 billion km (838.8 million mi; 9.024 AU) at its closest (perihelion) to 1.509 billion km (937.6 million mi; 10.086 AU) at its farthest (aphelion).

With an average orbital speed of 9.69 km/s, it takes Saturn 29.457 Earth years (or 10,759 Earth days) to complete a single revolution around the Sun. In other words, a year on Saturn lasts about as long as 29.5 years here on Earth. However, Saturn also takes just over 10 and a half hours (10 hours 33 minutes) to rotate once on its axis. This means that a single year on Saturn lasts about 24,491 Saturnian solar days.

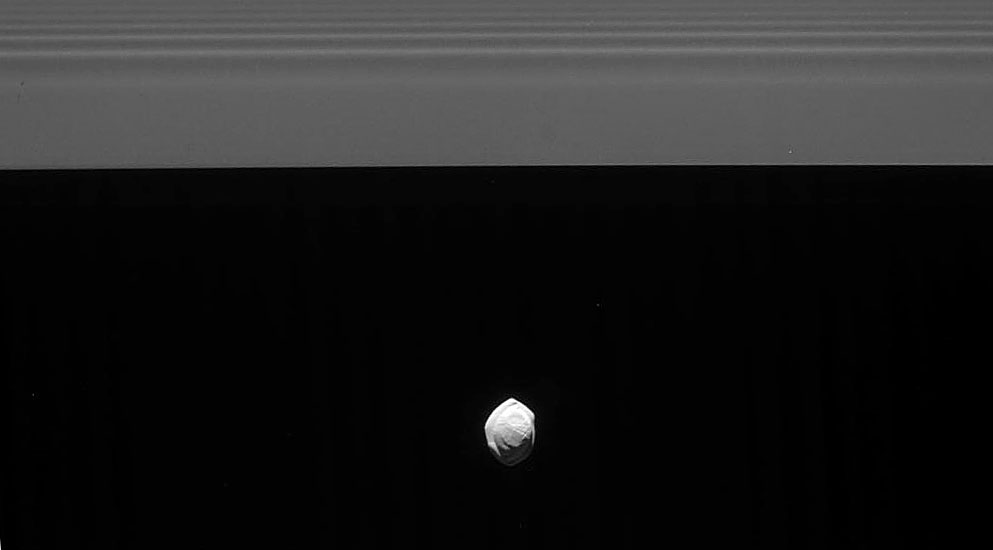

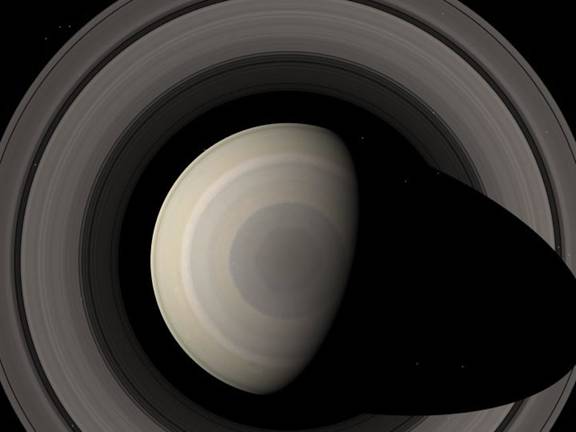

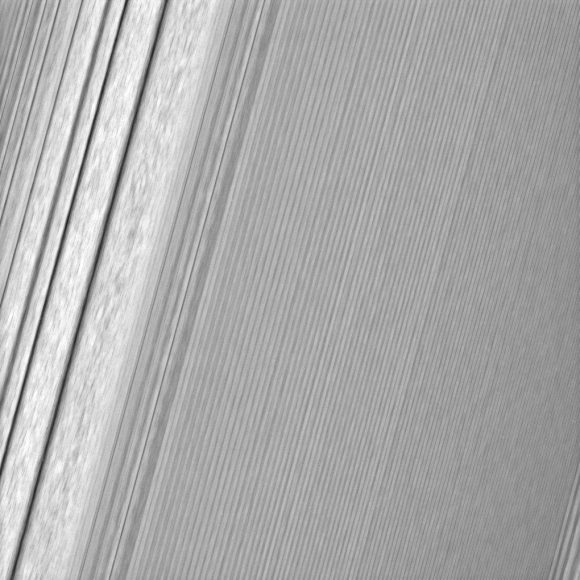

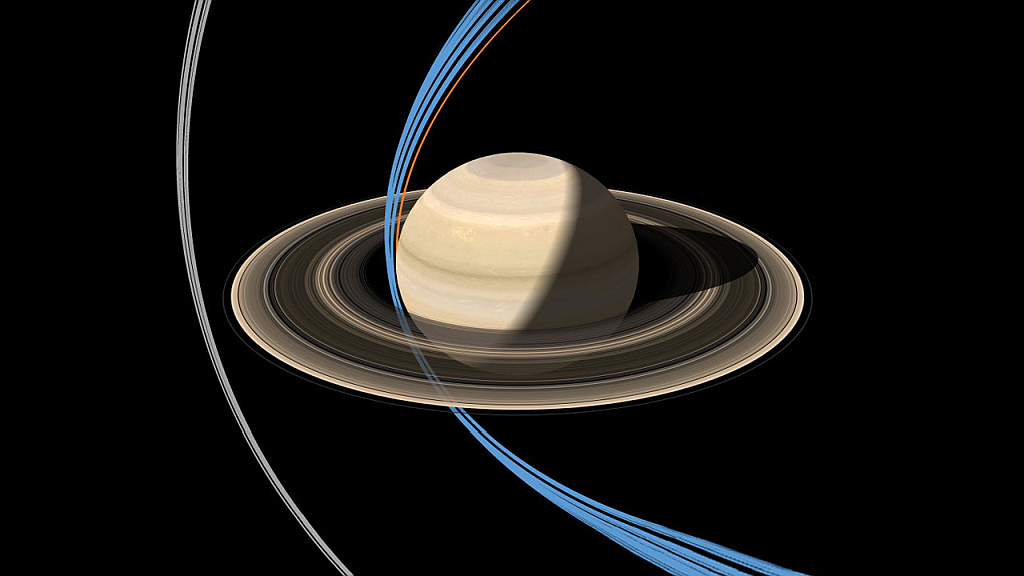

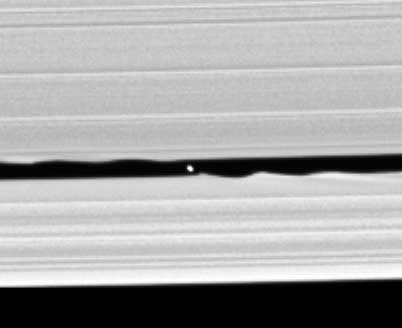

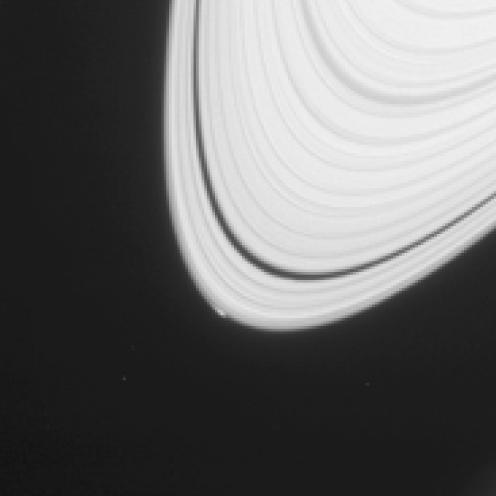

It is because of this that what we can see of Saturn’s rings from Earth changes over time. For part of its orbit, Saturn’s rings are seen at their widest point. But as it continues on its orbit around the Sun, the angle of Saturn’s rings decreases until they disappear entirely from our point of view. This is because we are seeing them edge-on. After a few more years, our angle improves and we can see the beautiful ring system again.

Orbital Inclination and Axial Tilt:

Another interesting thing about Saturn is the fact that its axis is tilted off the plane of the ecliptic. Essentially, its orbit is inclined 2.48° relative to the orbital plane of the Earth. Its axis is also tilted by 26.73° relative to the ecliptic of the Sun, which is similar to Earth’s 23.5° tilt. The result of this is that, like Earth, Saturn goes through seasonal changes during the course of its orbital period.

Seasonal Changes:

For half of its orbit, Saturn’s northern hemisphere receives more of the Sun’s radiation than the southern hemisphere. For other half of its orbit, the situation is reversed, with the southern hemisphere receiving more sunlight than the northern hemisphere. This creates storm systems that dramatically change depending on which part of its orbit Saturn is in.

For staters, winds in the upper atmosphere can reach speeds of up to 5oo meters per second (1,600 feet per second) around the equatorial region. On occasion, Saturn’s atmosphere exhibits long-lived ovals, similar to what is commonly observed on Jupiter. Whereas Jupiter has the Great Red Spot, Saturn periodically has what’s known as the Great White Spot (aka. Great White Oval).

This unique but short-lived phenomenon occurs once every Saturnian year, around the time of the northern hemisphere’s summer solstice. These spots can be several thousands of kilometers wide, and have been observed on many occasions throughout the past – in 1876, 1903, 1933, 1960, and 1990.

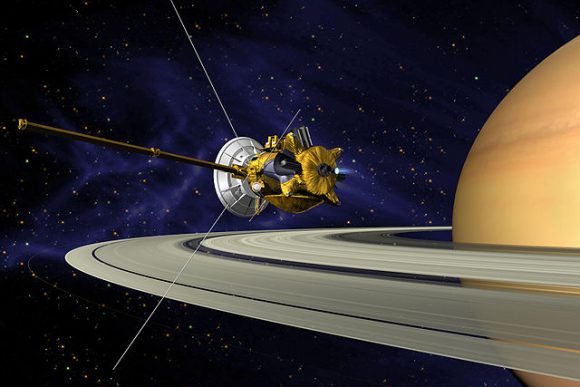

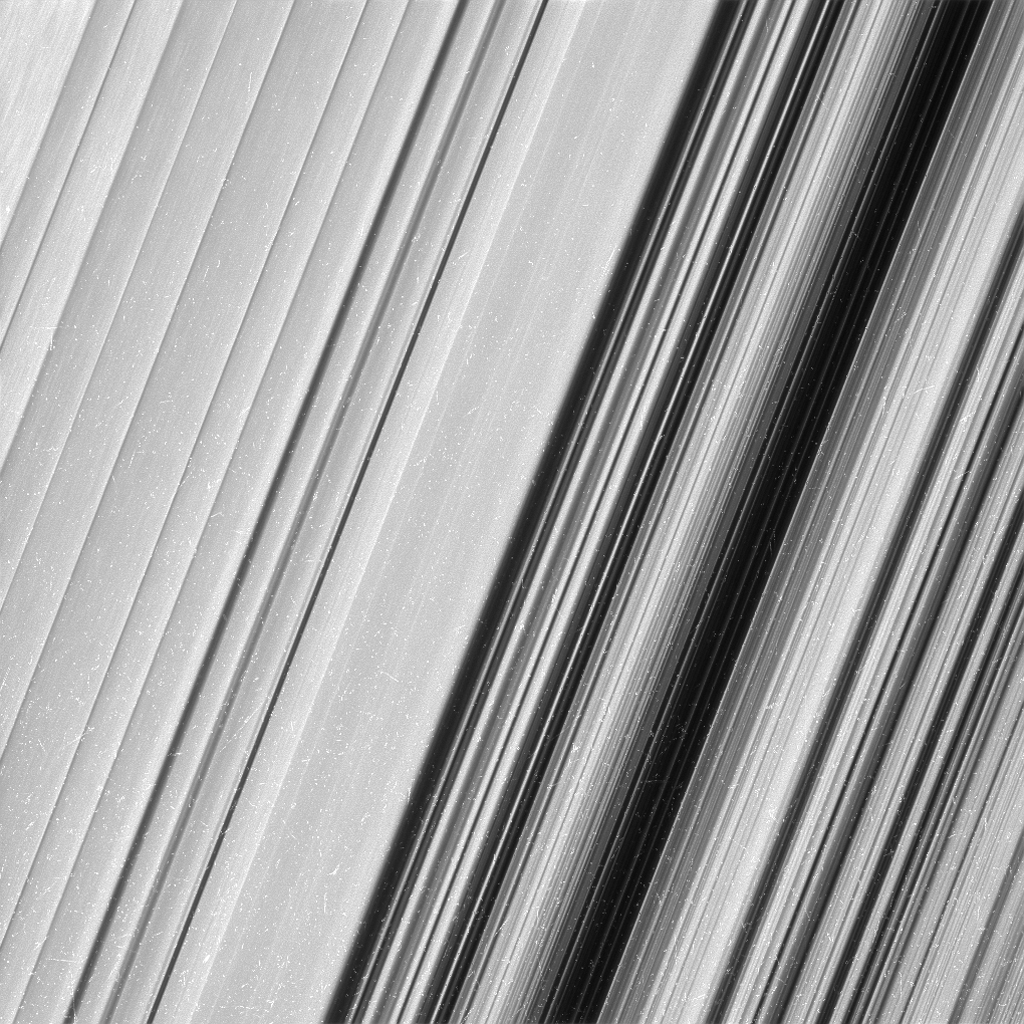

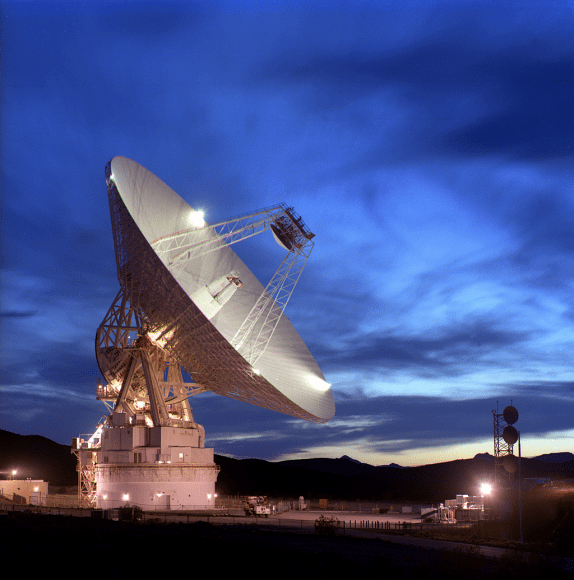

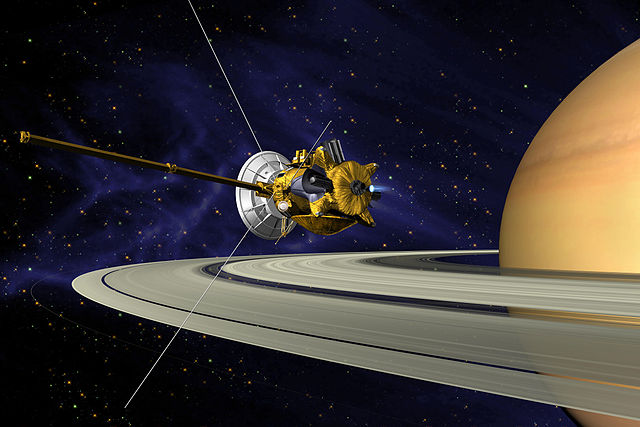

Since 2010, a large band of white clouds called the Northern Electrostatic Disturbance have been observed, which was spotted by the Cassini space probe. Given the periodic nature of these storms, another one is expected to happen in 2020, coinciding with Saturn’s next summer in the northern hemisphere.

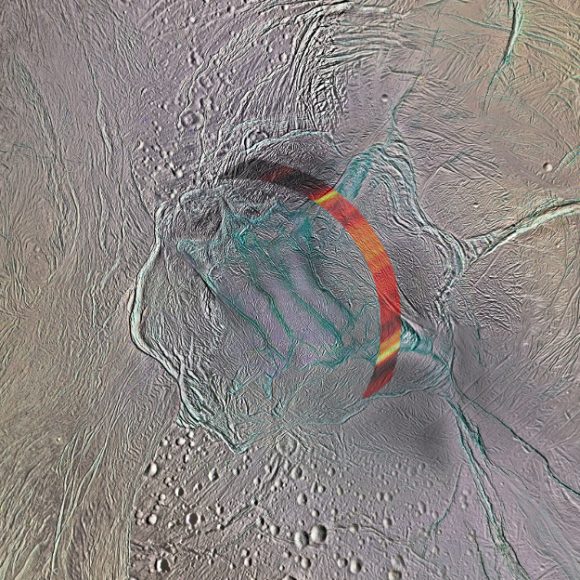

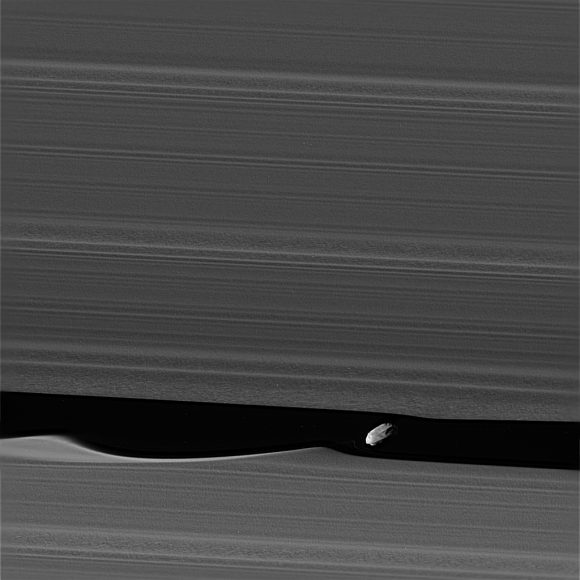

Similarly, seasonal changes affect the very large weather patterns that exist around Saturn’s northern and southern polar regions. At the north pole, Saturn experiences a hexagonal wave pattern which measures some 30,000 km (20,000 mi) in diameter, while each of it six sides measure about 13,800 km (8,600 mi). This persistent storm can reach speeds of about 322 km per hour (200 mph).

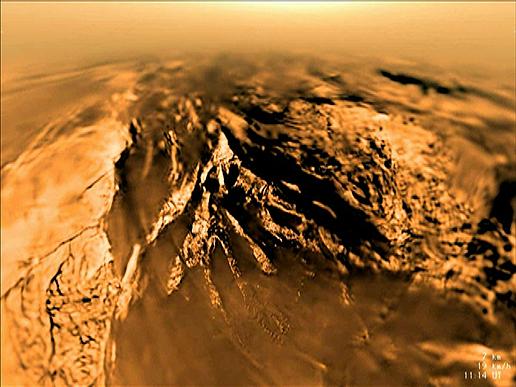

Thanks to images taken by the Cassini probe between 2012 and 2016, the storm appears to undergo changes in color (from a bluish haze to a golden-brown hue) that coincide with the approach of the summer solstice. This was attributed to an increase in the production of photochemical hazes in the atmosphere, which is due to increased exposure to sunlight.

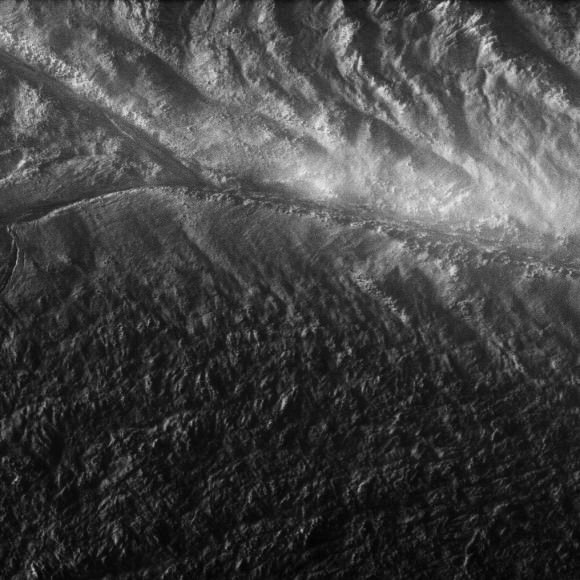

Similarly, in the southern hemisphere, images acquired by the Hubble Space Telescope have indicated the existence of large jet stream. This storm resembles a hurricane from orbit, has a clearly defined eyewall, and can reach speeds of up to 550 km/h (~342 mph). And much like the northern hexagonal storm, the southern jet stream undergoes changes as a result of increased exposure to sunlight.

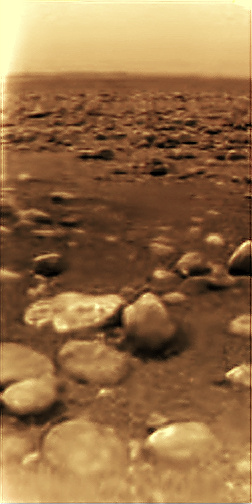

Cassini was able to captured images of the south polar region in 2007, which coincided with late fall in the southern hemisphere. At the time, the polar region was becoming increasingly “smoggy”, while the northern polar region was becoming increasingly clear. The reason for this, it was argued, was that decreases in sunlight led to the formation of methane aerosols and the creation of cloud cover.

From this, it has been surmised that the polar regions become increasingly obscured by methane clouds as their respective hemisphere approaches their winter solstice, and clearer as they approach their summer solstice. And the mid-latitudes certainly show their share of changes thanks to increases/decreases in exposure to solar radiation.

Much like the length of a single year, what we know about Saturn has a lot to do with its considerable distance from the Sun. In short, few missions have been able to study it in depth, and the length of a single year means it is difficult for a probe to witness all the seasonal changes the planet goes through. Still, what we have learned has been considerable, and also quite impressive!

We have written many articles about years on other planets here at Universe Today. Here’s The Orbit of the Planets. How Long Is A Year On The Other Planets?, The Orbit of Earth. How Long is a Year on Earth?, The Orbit of Mercury. How Long is a Year on Mercury?, The Orbit of Venus. How Long is a Year on Venus?, The Orbit of Mars. How Long is a Year on Mars?, The Orbit of Jupiter. How Long is a Year on Jupiter?, The Orbit of Uranus. How Long is a Year on Uranus?, The Orbit of Neptune. How Long is a Year on Neptune?, The Orbit of Pluto. How Long is a Year on Pluto?

If you’d like more information on Saturn, check out Hubblesite’s News Releases about Saturn. And here’s a link to the homepage of NASA’s Cassini spacecraft, which is orbiting Saturn.

We have also recorded an entire episode of Astronomy Cast that’s just about Saturn. Listen here, Episode 59: Saturn.

Sources: