Image credit: NASA/JPL/Space Science Institute

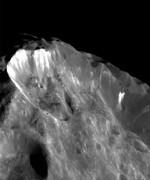

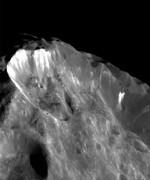

Images collected during the Cassini-Huygens close fly-by of Saturn’s moon Phoebe give strong evidence that the tiny moon may be rich in ice and covered by a thin layer of darker material.

Its surface is heavily battered, with large and small craters. It might be an ancient remnant of the formation of the Solar System.

On Friday 11 June, at 21:56 CET, the Cassini-Huygens spacecraft flew by Saturn’s outermost moon Phoebe, coming within approximately 2070 kilometres of the satellite’s surface. All eleven on-board instruments scheduled to be active at that time worked flawlessly and acquired data.

The first high-resolution images show a scarred surface, covered with craters of all sizes and large variation of brightness across the surface.

Phoebe is a peculiar moon amongst the 31 known satellites orbiting Saturn. Most of Saturn’s moons are bright but Phoebe is very dark and reflects only 6% of the Sun’s light. Another difference is that Phoebe revolves around the planet on a rather elongated orbit and in a direction opposite to that of the other large moons (a motion known as ‘retrograde’ orbit).

All these hints suggested that Phoebe, rather than forming together with Saturn, was captured at a later stage. Scientists, however, do not know whether Phoebe was originally an asteroid or an object coming from the ‘Kuiper Belt’.

The stunning images obtained by Cassini’s high-resolution camera now seem to indicate that it contains ice-rich material and is covered by a thin layer of dark material, probably 300-500 metres thick.

Scientists base this hypothesis on the observation of bright streaks in the rims of the largest craters, bright rays radiating from smaller craters, grooves running continuously across the surface of the moon and, most importantly, the presence of layers of dark material at the top of crater walls.

“The imaging team is in hot debate at the moment on the interpretations of our findings,” said Dr Carolyn Porco, Cassini imaging team leader at the Space Science Institute in Boulder, USA.

“Based on our images, some of us are leaning towards the view that has been promoted recently, that Phoebe is probably ice-rich and may be an object originating in the outer solar system, more related to comets and Kuiper Belt objects than to asteroids.”

The high-resolution images of Phoebe show a world of dramatic landforms, with landslides and linear structures such as grooves, ridges and chains of pits. Craters are ubiquitous, with many smaller than one kilometre.

“This means, besides the big ones, lots of projectiles smaller than 100 metres must have hit Phoebe,” said Prof. Gerhard Neukum, Freie Universitaet Berlin, Germany, and a member of the imaging team. Whether these projectiles came from outside or within the Saturn system is debatable.

There is a suspicion that Phoebe, the largest of Saturn’s outer moons, might be parent to the other, much smaller retrograde outer moons that orbit Saturn. They could have resulted from the impact ejecta that formed the many craters on Phoebe.

Besides these stunning images, the instruments on board Cassini collected a wealth of other data, which will allow scientists to study the surface structures, determine the mass and composition of Phoebe and create a global map of it.

“If these additional data confirm that Phoebe is mostly ice, covered by layers of dust, this could mean that we are looking at a ‘leftover’ from the formation of the Solar System about 4600 million years ago,” said Dr Jean-Pierre Lebreton, ESA Huygens Project Scientist.

Phoebe might indeed be an icy wanderer from the distant outer reaches of the Solar System, which, like a comet, was dislodged from the Kuiper Belt and captured by Saturn when the planet was forming.

Whilst studying the nature of Phoebe may give scientists clues on the origin of the building blocks of the Solar System, more data are needed to reconstruct the history of our own neighbourhood in space.

With that aim, ESA’s Rosetta mission is on its way to study one of these primitive objects, Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, from close quarters for over a year and land a probe on it.

The fly-by of Phoebe on 11 June was the only one that Cassini-Huygens will perform with this mysterious moon. The mission will now take the spacecraft to its closest approach to Saturn on 1 July, when it will enter into orbit around the planet.

From there, it will conduct 76 orbits of Saturn over four years and execute 52 close encounters with seven other Saturnian moons. Of these, 45 will be with the largest and most interesting one, Titan. On 25 December, Cassini will release the Huygens probe, which will descend through Titan’s thick atmosphere to investigate its composition and complex organic chemistry.

Original Source: ESA News Release