“Nothing in biology makes sense”, wrote the evolutionary biologist Theodosius Dobzhansky, “except in the light of evolution”. If we want to assess whether it is likely that technological civilizations have evolved on alien planets or moons, and what they might be like, the theory of evolution is our best guide. On May 18, 2016 the newly founded METI (Messaging to ExtraTerrestrial Intelligence) International hosted a workshop entitled ‘The Intelligence of SETI: Cognition and Communication in Extraterrestrial Intelligence’. The workshop was held in San Juan, Puerto Rico on the first day of the National Space Society’s International Space Development Conference. It included nine talks by scientists and scholars in evolutionary biology, psychology, cognitive science, and linguistics.

In the first instalment of this series, we saw that intelligence, of various sorts, is widespread across the animal kingdom. Workshop presenter Anna Dornhaus, who studies collective decision-making in insects as an associate professor at the University of Arizona, showed that even insects, with their diminutive brains, exhibit a surprising cognitive sophistication. Intelligence, of various sorts, is a likely and probable evolutionary product.

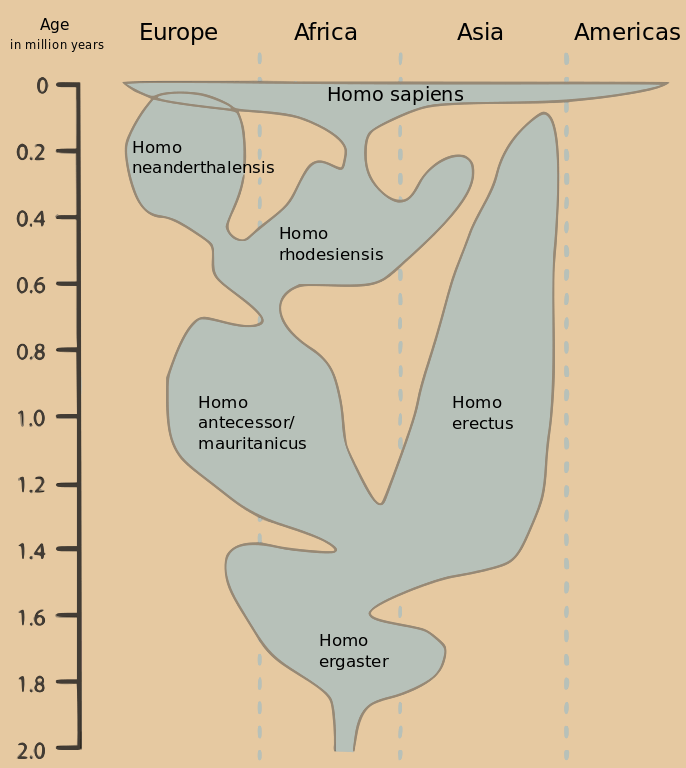

Animals evolve the cognitive abilities that they need to meet the demands of their own particular environments and lifestyles. Sophisticated brains and cognition have evolved many times on Earth, in many separate evolutionary lineages. But, of the millions of evolutionary lineages that have arisen on Earth in the 600 million years since complex life appeared, only one, that which led to human beings, produced the peculiar combination of cognitive traits that led to a technological civilization. What this tells us is that technological civilization is not the inevitable product of a long term evolutionary trend, it is rather the quirky and contingent product of particular circumstances. But what might those circumstances have been, and just how special and improbable were they?

Workshop presenter Geoffrey Miller is an associate professor of psychology at the University of New Mexico. Miller thinks he has an answer to the question of what the special circumstances that produced human evolution were. Our protohuman ancestors inhabited the African savanna. But so do many other mammals that don’t need enormous brains to survive there. The evolutionary forces driving the production of our large brains, Miller surmises, can’t be due to the challenges of survival. He thinks instead that human evolution was guided by an intelligence. But Miller is no creationist, nor does he have the alien monolith from the 1960’s science fiction classic 2001: A Space Odyssey in mind. Miller’s guiding intelligence is the intelligence that our ancestors themselves used when they selected their mates.

Miller’s theory harkens back to the ideas of the founder of modern evolutionary theory, the nineteenth century British naturalist Charles Darwin. Darwin proposed that evolution works through a process of natural selection. Animal offspring vary one from another, and are produced in too great of numbers for all of them to survive. Some starve, some are eaten by predators, others fall prey to the numerous other hazards of the natural world. A few survive to produce offspring, thereby passing on the traits that allowed them to survive. Down the generations, traits that aided survival become more elaborate and useful and traits that did not, vanished.

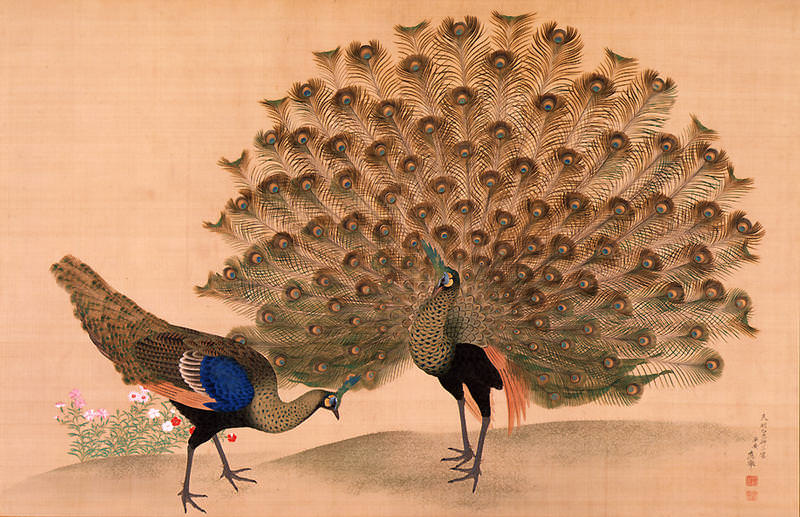

But Darwin was troubled by a serious problem with his theory. He knew that many animals have prominent traits that don’t seem to contribute to their survival, and are even counterproductive to it. The bright colors of many insects, the colors, elaborate plumage, and songs of birds, the huge antlers of elk, were all prominent and costly traits that couldn’t be explained by his theory of natural selection. Peacocks, with their elaborate tail feathers were everywhere in English gardens, and came to torment him.

At last, Darwin found the solution. To produce offspring, an animal must do more than just survive, it must find a partner to mate with. All the traits which worried Darwin could be explained if they served to make their bearers sexier and more beautiful to prospective mates than other competing members of their own gender. If peahens like elaborate plumage, then in each generation, they will choose to mate with the males with the most elaborate tail feathers, and reject the rest. Through the competition for mates, peacock tails will become more and more elaborate down the generations. Darwin called his new theory sexual selection.

Many subsequent evolutionary biologists regarded sexual selection as of limited importance, and lumped it in with natural selection, which was said to favor traits conducive to survival and reproductive success. However, in recent decades evolutionary biologists have come to view sexual selection in a much more favorable light. Geoffrey Miller proposed that the human brain evolved through sexual selection. Human beings, he supposes, are sapiosexual; that is, they are sexually attracted by intelligence and its products. The preference for selecting intelligent mates produced greater intelligence, which in turn allowed our ancestors to become more discerning in selecting more intelligent mates, producing a kind of amplifying feedback loop, and an explosion of intelligence.

On this account, language, music, dancing, humor, art, literature, and perhaps even morality and ethics exist because those who were good at them were deemed sexier, or more trustworthy and reliable, and were thus more successful in securing mates than those who weren’t. The elaborate human brain is like the elaborate peacock’s tail. It exists for wooing mates and not for survival. There are some important ways in which protohumans were different from peafowl. Both males and females are choosy and both have large brains. Protohumans, unlike peafowl, probably formed monogamous pair bonds. Miller’s theory has complexities that space won’t permit us to explore here. To show that his theory can work, Miller needed to develop a computer model.

If Miller is right, then just how probable is the evolution of a technological civilization, and how likely is it that we will find them elsewhere in the galaxy? Miller thinks that if complex life exists on other planets or moons, it is likely to evolve reproduction through sex, just as has happened here on Earth. For complex organisms that depend on a large and complicated body of genetic information, most mutations will be neutral or harmful. In sexual reproduction half the genes of one’s offspring come from each parent. Without this mixing of genes from other individuals, asexual lineages are likely to falter and go extinct due to an accumulation of harmful mutations. Unless sexually reproducing creatures choose their mates purely at random, sexual selection is an inevitability. So, the basic conditions for runaway sexual selection to produce a brain suited to language and technology probably exists on other worlds with complex life.

One problem, though, that Anna Dornhaus pointed out, is that in sexual selection, the trait that gets exaggerated is essentially arbitrary. There are many bird species with elaborate plumage, but none exactly like the peacock. There are many species where brains and cognitive traits matter for mating success, like the singing ability of nightingales and many other birds, or gibbons, or whales. Male bower birds build complicated structures, called bowers, out of found items, like sticks and leaves and stones and shells, to attract a female. Chimpanzees engage in complex power struggles that involve negotiation, grooming, and fighting their way to the top.

But despite the selective success of cognition and braininess in many species, our specific human sort of intelligence, with language and technology, has happened only once on Earth, and therefore might be rare in the universe. If our ancestors had found big noses rather than big brains sexy, then we might now have enormous noses rather than enormous radio telescopes capable of signaling to other worlds.

Miller is more optimistic. “It’s a rare accident” he writes, in the sense that mate preferences only rarely turn ‘sapiosexual’, focused so heavily on conspicuous displays of general intelligence… On the other hand, I think it’s likely that in any biosphere, sexual selection would eventually stumble into sapiosexual mate preferences, and then you’d get human-level intelligence and language of some sort. It might only arise in 1 out of every 100 million species though,…I suspect that in any biosphere with sexually reproducing complex organisms and a wide variety of species, you’d quite likely get at least one lineage stumbling into the sapiosexual niche within a billion years”.

A planet or moon is currently deemed potentially habitable if it orbits its parent star within the right distance range for liquid water to exist on its surface. This distance range is called the habitable zone. Since stars evolve with time, the duration of habitability is limited. Such matters can be explored through climate modeling, informed by what we know of the climates of Earth and other worlds within our solar system, and about the evolution of stars.

Current thinking is that Earth’s total duration of habitability is 6.3 to 7.8 billion years, and that our world may remain habitable for another 1.75 billion years. Since complex life has already existed on Earth for 600 million years, this seems a generous amount of time for complex life on a similar planet to stumble upon Miller’s sapiosexual niche. Stars of smaller mass than the sun are stable on longer timescales, some perhaps capable of sustaining worlds with liquid water for a hundred billion years. If Miller’s estimates are reasonable, then there may be worlds enough and time for an abundance of sapiosexual alien civilizations in our galaxy.

A central message of the METI Institute workshop is that, animals evolve whatever sort of intelligence is necessary for them to survive and reproduce under the circumstances in which they find themselves. Human-style intelligence, with language and technology, is a peculiar quirk of particular and improbable evolutionary circumstances. But we don’t know just how improbable. Given the vastness of time and number of worlds potentially available for the roll of the evolutionary dice, alien civilizations might be reasonably abundant, or they might be once-in-a-billion galaxies rare. We just don’t know. Better knowledge of the evolution of life and intelligence here on Earth might allow us to improve our estimates.

If alien civilizations do exist, what can life on Earth tell us about what their minds and senses are likely to be like? Are they, like us, visually oriented creatures, or might they rely on other senses? Can we expect that their minds might be similar enough to ours to make meaningful communication possible? These intriguing questions will be the subject of the third and final installment of this series.

For further reading:

Hooper, P. L. (2008) Mutual mate choice can drive costly signalling even under perfect monogamy. Adaptive Behavior, 16: p. 53-70.

Marris, E. (2013) Earth’s days are numbered. Nature News.

Miller, G. F. (2000) The Mating Mind: How Sexual Choice Shaped the Evolution of Human Nature. Random House, New York.

Miller, G. F. (2007) Sexual selection for moral virtues, The Quarterly Review of Biology, 82(2): p. 97-125.

Patton, P. E. (2016) Alien Minds I: Are Extraterrestrial Civilizations Likely to Evolve? Universe Today.

P. Patton (2014) Communicating across the cosmos, Part 1: Shouting into the darkness, Part 2: Petabytes from the Stars, Part 3: Bridging the Vast Gulf, Part 4: Quest for a Rosetta Stone, Universe Today.

Rushby, A. J., Claire, M. W., Osborn, H., Watson, A. J. (2013) Habitable zone lifetimes of exoplanets around main sequence stars. Astrobiology, 13(9), p. 833-849.

Yirka, B. (2016) Yeast study offers evidence of the superiority of sexual reproduction versus cloning in speed of adaptation. Phys.org.

![The Standard Model of Elementary Particles. Image: By MissMJ - Own work by uploader, PBS NOVA [1], Fermilab, Office of Science, United States Department of Energy, Particle Data Group, CC BY 3.0](https://www.universetoday.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Standard_Model_of_Elementary_Particles.svg_-580x436.png)