As NASA’s Opportunity rover approaches the 12th anniversary of landing on Mars, her greatest science discoveries yet are likely within grasp in the coming months since she has successfully entered Marathon Valley from atop a Martian mountain and is now prospecting downhill for outcrops of water altered clay minerals.

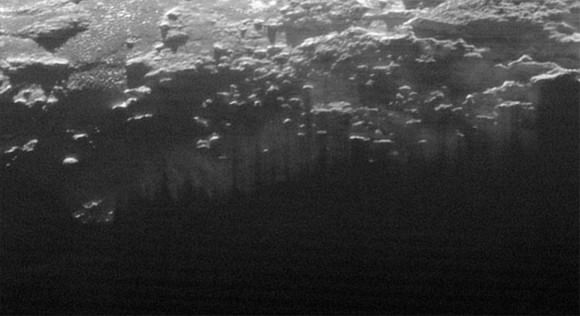

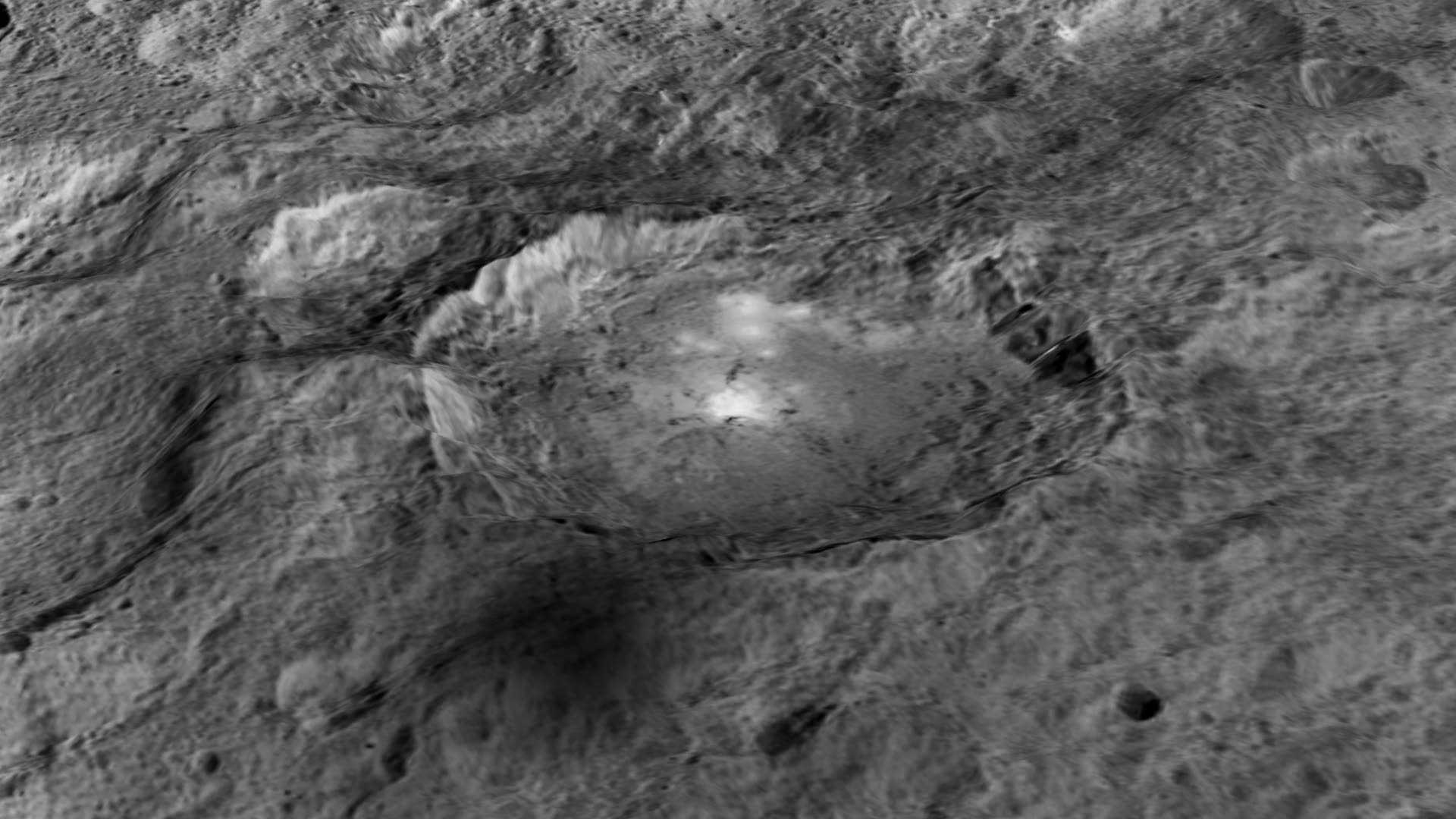

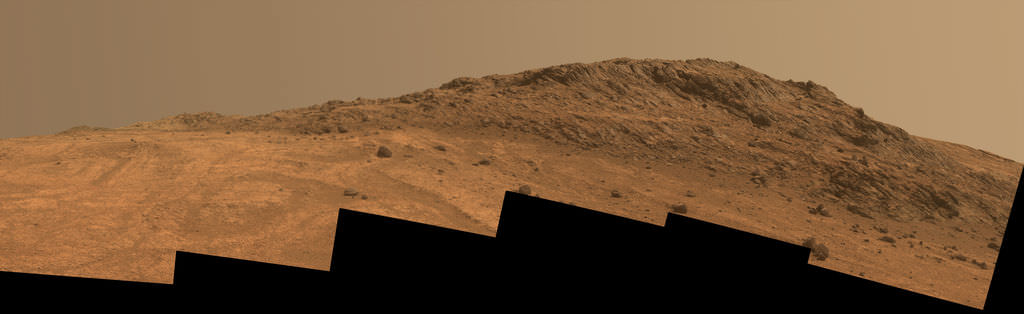

The valley is the gateway to alien terrain holding significant caches of the water altered minerals that formed under environmental conditions conducive to support Martian microbial life forms, if they ever existed. But as anyone who’s ever climbed down a steep hill knows, you have to be extra careful not to slip and slide and break something, no matter how beautiful the view is – Because no one can hear you scream on Mars! See the downward looking valley view above.

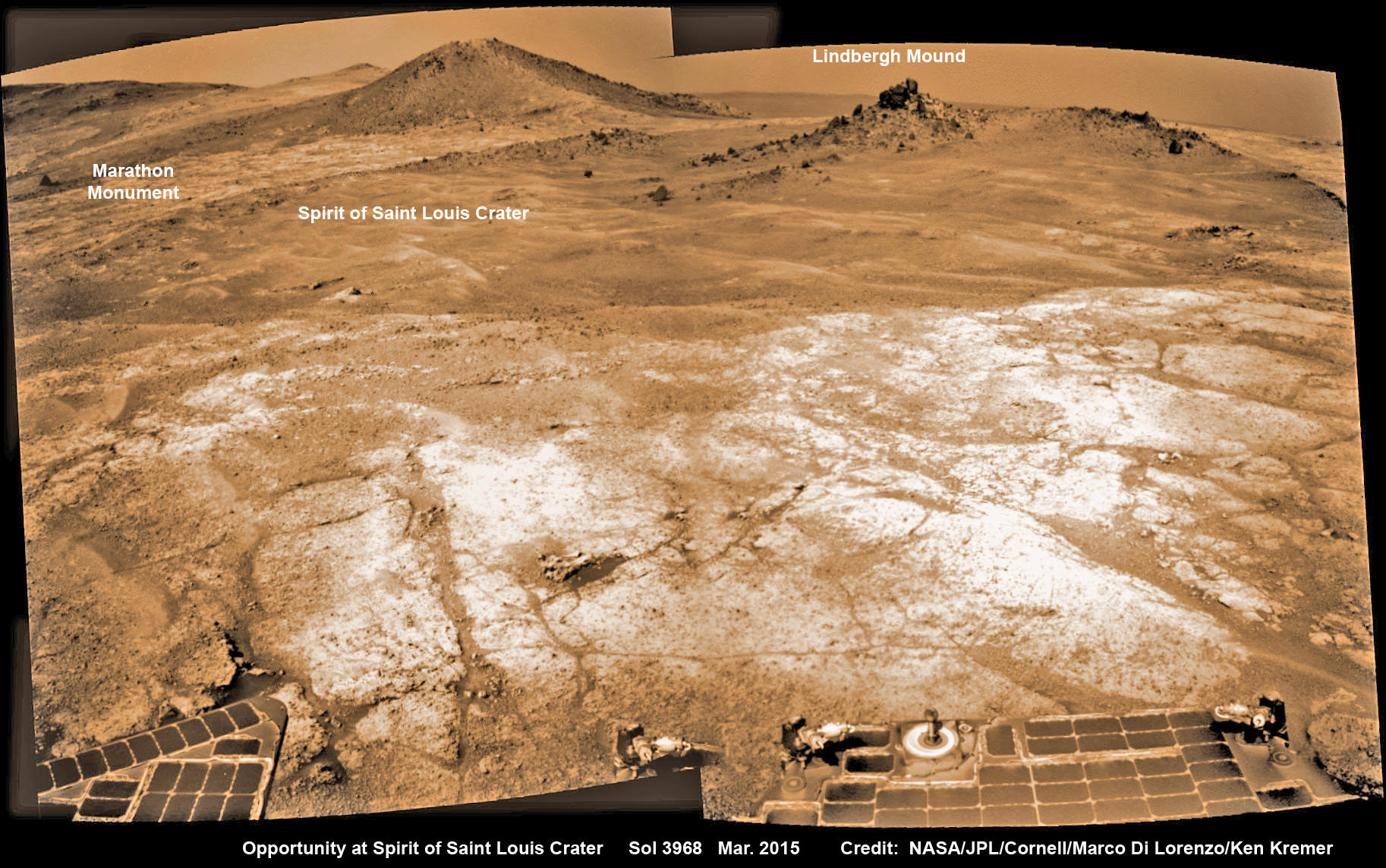

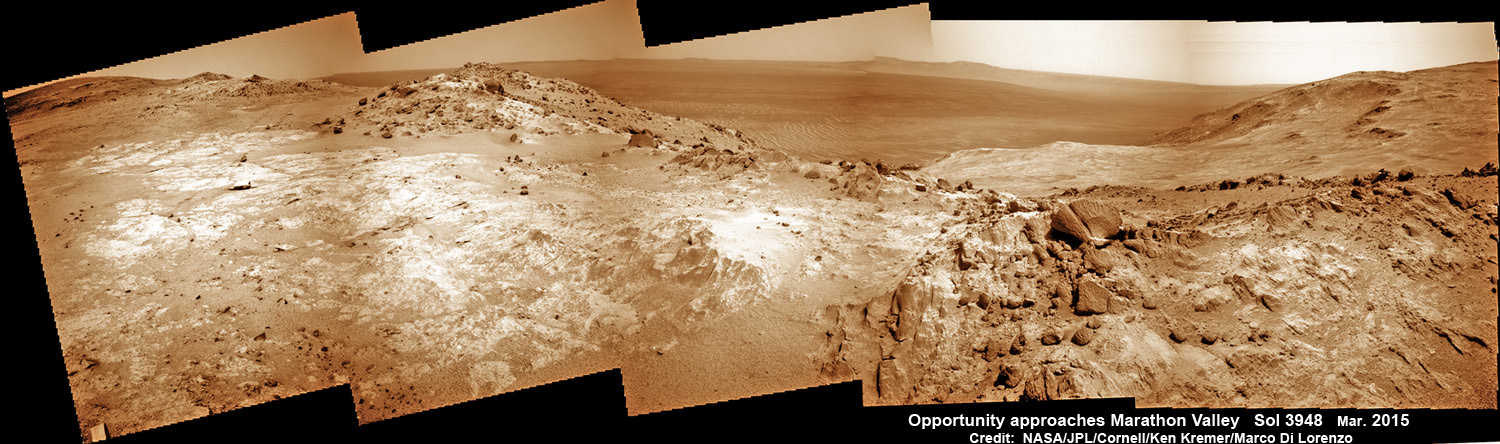

After a years long Martian mountain climbing and mountain top exploratory trek, Opportunity entered a notch named Marathon Valley from atop a breathtakingly scenic ridge overlook atop the western rim of Endeavour Crater.

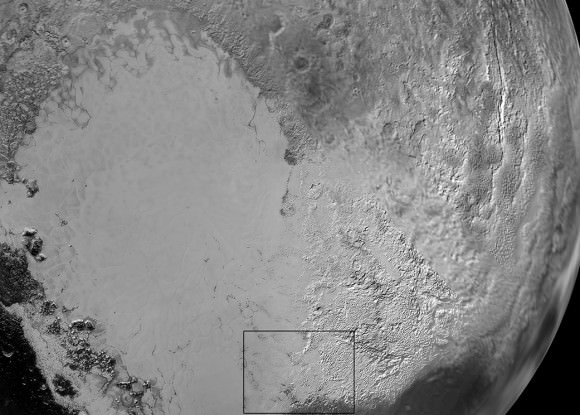

Marathon Valley measures about 300 yards or meters long and cuts downhill through the west rim of Endeavour crater from west to east. Endeavour crater spans some 22 kilometers (14 miles) in diameter.

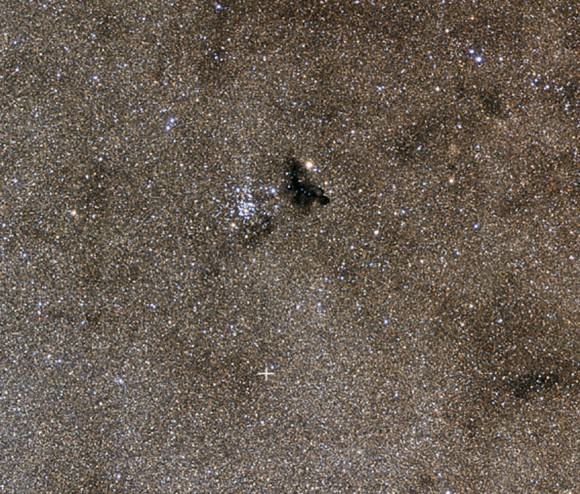

See our photo mosaics illustrating Opportunity’s view around and about Marathon Valley and Endeavour Crater, created by the image processing team of Ken Kremer and Marco Di Lorenzo.

Our mosaic above affords a downward looking view from Marathon Valley on Sol 4144, Sept. 20. It uniquely combines raw images from the hazcam and navcam cameras to gain a wider perspective panoramic view of the steep walled valley, and also shows the rover at work stretching out the robotic arm to potential clay mineral rock targets at left. Opportunity’s shadow and wheel tracks are visible at right.

In late July, Opportunity began the decent into the valley from the western edge and started investigating scientifically interesting rock targets by conducting a month’s long “walkabout” survey ahead of the upcoming frigid Martian winter – the seventh since touchdown at Meridiani Planum in January 2004.

The walkabout was done to identify targets of interest for follow up scrutiny in and near the valley floor. Opportunity’s big sister Curiosity conducted a similarly themed “walkabout” at the base of Mount Sharp near her landing site located on the opposite side of the Red Planet.

“The valley is somewhat like a chute directed into the crater floor, which is a long ways below. So it is somewhat scary, but also pretty interesting scenery,” writes Larry Crumpler, a science team member from the New Mexico Museum of Natural History & Science, in a mission update.

“Its named Marathon Valley because the rover traveled one marathon’s distance to reach it,” Prof. Ray Arvidson, the rover Deputy Principal Investigator of Washington University told Universe Today.

The NASA rover exceeded the distance of a marathon on the surface of Mars on March 24, 2015, Sol 3968. Opportunity has now driven over 26.46 miles (42.59 kilometers) over nearly a dozen Earth years.

Now for the first time in history, a human emissary has arrived to conduct an up close inspection of and elucidate clues into this regions potential regarding Martian habitability.

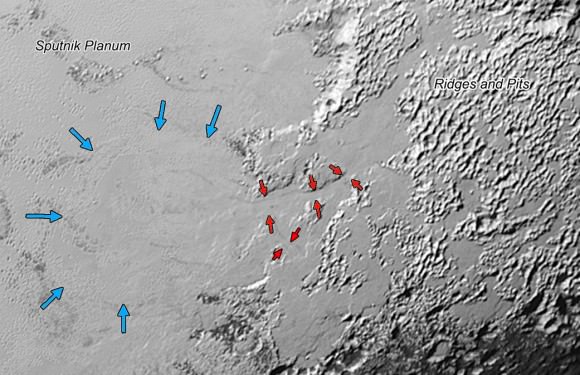

The ancient, weathered slopes around Marathon Valley hold a motherlode of ‘phyllosilicate’ clay minerals, based on data obtained from the extensive Mars orbital measurements gathered by the CRISM spectrometer on NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) – accomplished earlier at the direction of Arvidson.

Initially the science team was focused on investigating the northern region of the valley while the sun was still higher in the sky and generating more power for research activities from the life giving solar arrays.

“We have detective work to do in Marathon Valley for many months ahead,” said Opportunity Deputy Principal Investigator Ray Arvidson, of Washington University in St. Louis.

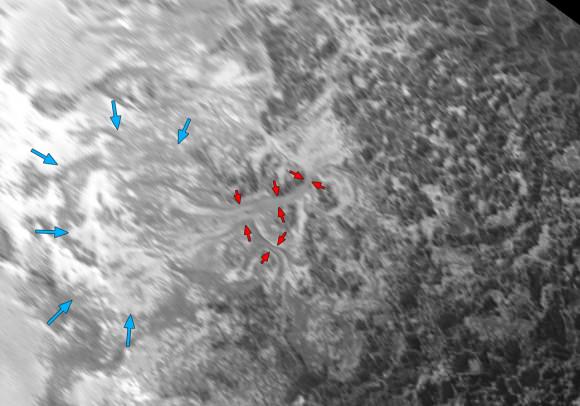

But now that the rover is descending into a narrow valley with high walls, the rovers engineering handlers back on Earth have to exercise added caution regarding exactly where they send the Opportunity on her science forays during each sols drive, in order to maintain daily communications.

The high walls to the north and west of the valley ridgeline has already caused several communications blackouts for the “low-elevation Ultra-High-Frequency (UHF) relay passes to the west,” according to the JPL team controlling the rover.

Indeed on two occasions in mid September – coinciding with the days just before and after our Sol 4144 (Sept. 20) photo mosaic view above, “no data were received as the orbiter’s flight path was below the elevation on the valley ridgeline.

On Sept 17 and Sept. 21 “the high ridgeline of the valley obscured the low-elevation pass” and little to no data were received. However the rover did gather imagery and spectroscopic measurements for later transmission.

Now that winter is approaching the rover is moving to the southern side of Marathon Valley to soak up more of the sun’s rays from the sun-facing slope and continue research activities.

“During the Martian late fall and winter seasons Opportunity will conduct its measurements and traverses on the southern side of the valley,” says Arvidson.

“When spring arrives the rover will return to the valley floor for detailed measurements of outcrops that may host the clay minerals.”

The shortest-daylight period of this seventh Martian winter for Opportunity will come in January 2016.

As of today, Sol 4168, Oct, 15, 2015 Opportunity has taken over 206,300 images and traversed over 26.46 miles (42.59 kilometers).

Stay tuned here for Ken’s continuing Earth and planetary science and human spaceflight news.

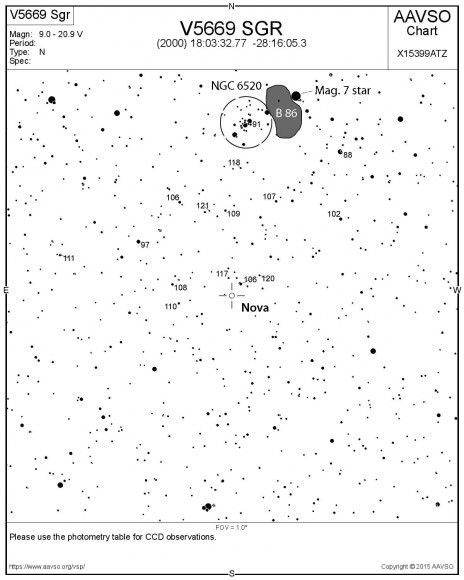

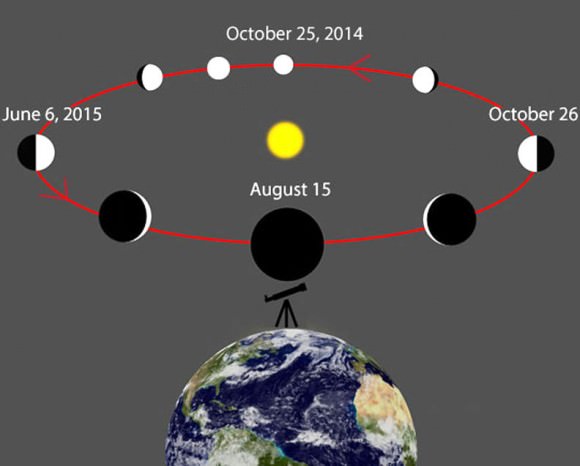

This map shows the entire path the rover has driven during almost 12 years and more than a marathon runners distance on Mars for over 4163 Sols, or Martian days, since landing inside Eagle Crater on Jan 24, 2004 – to current location at the western rim of Endeavour Crater and descending into Marathon Valley. Rover surpassed Marathon distance on Sol 3968 and marked 11th Martian anniversary on Sol 3911. Opportunity discovered clay minerals at Esperance – indicative of a habitable zone – and is currently searching for more at Marathon Valley. Credit: NASA/JPL/Cornell/ASU/Marco Di Lorenzo/Ken Kremer/kenkremer.com