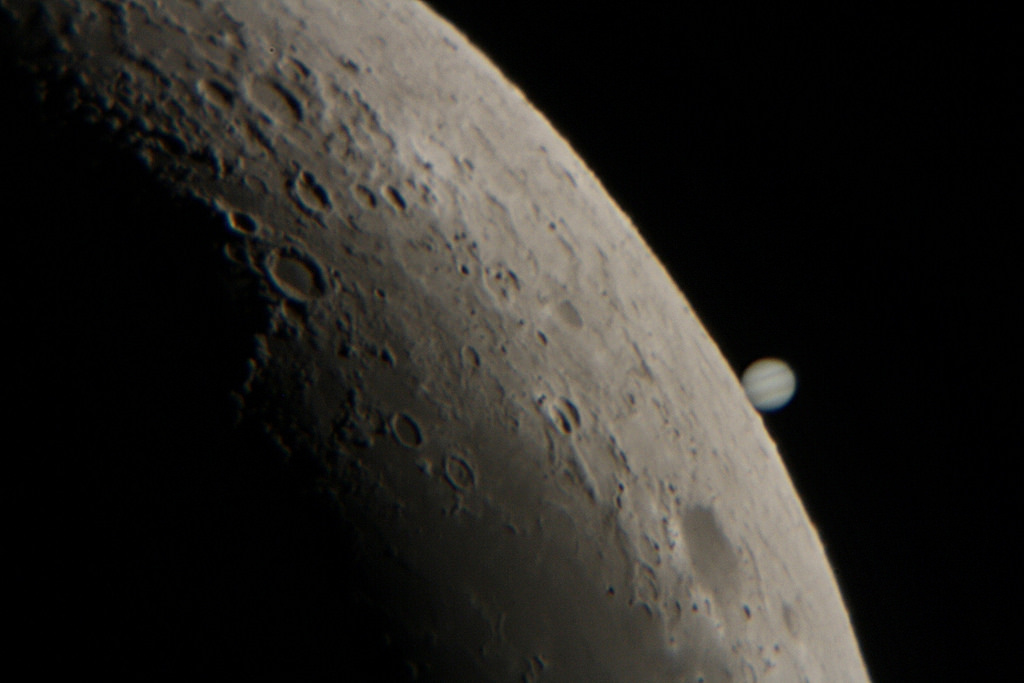

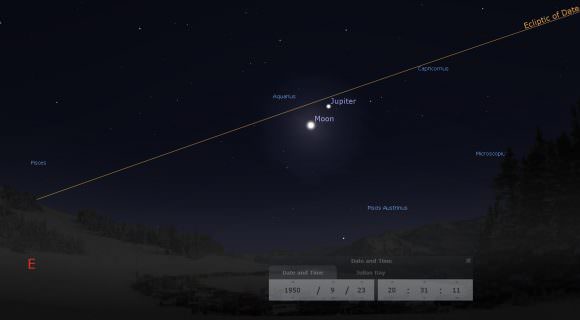

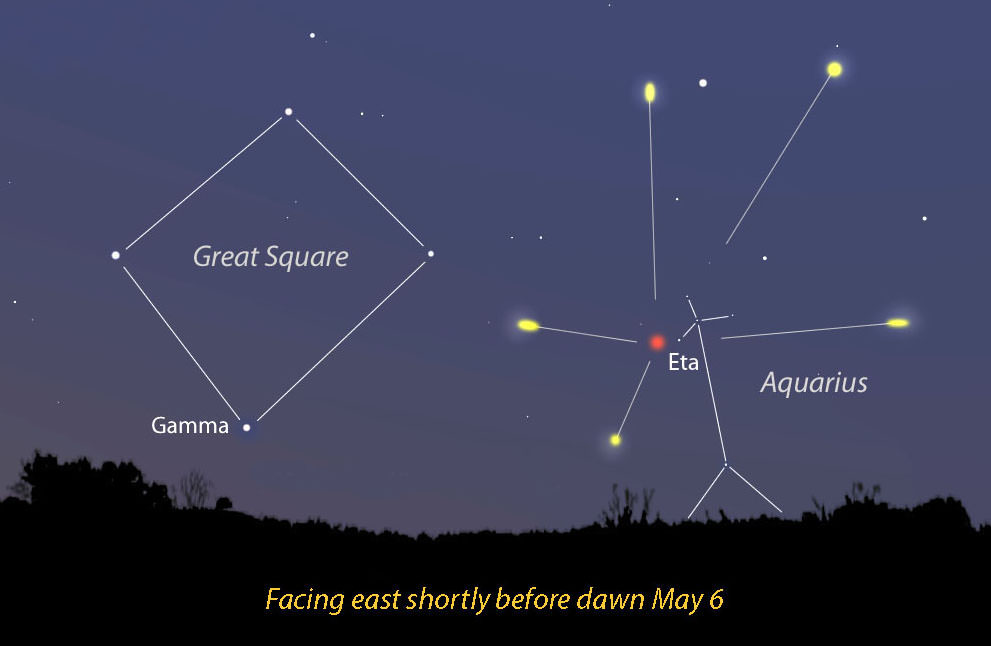

So, are you catching sight of the waxing crescent Moon returning this week to the early PM sky? The start of lunation 1157 gives folks observing Ramadan here in Morocco a reason to celebrate, as it marks the end of dawn-to-dusk fasting. Follow that Moon, as it’s about to meet up with the king of the planets this weekend.

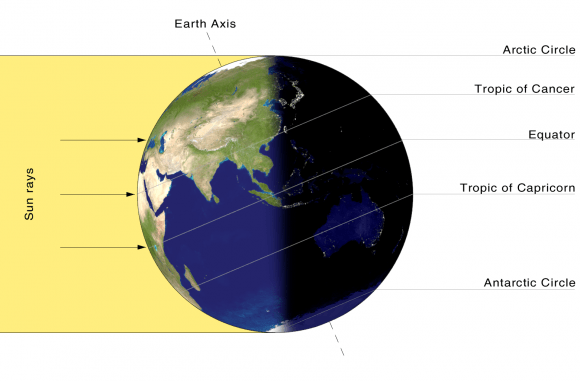

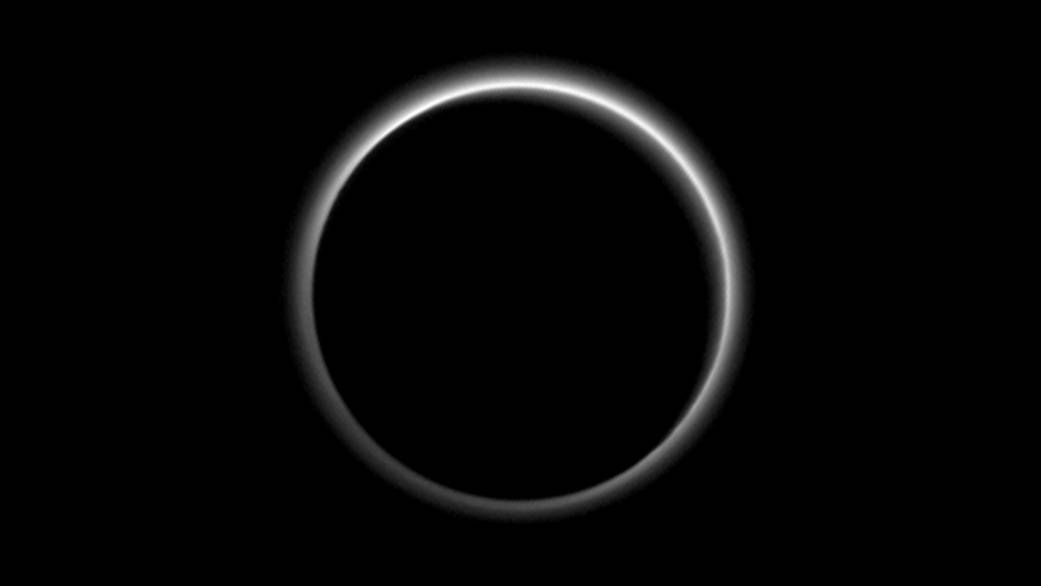

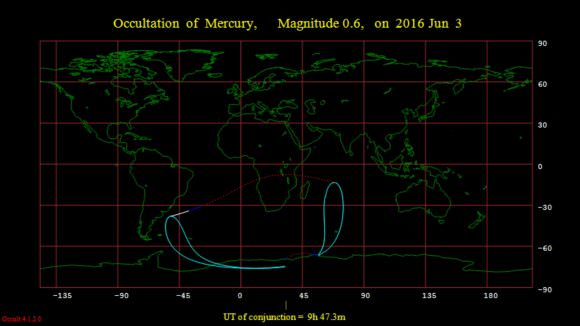

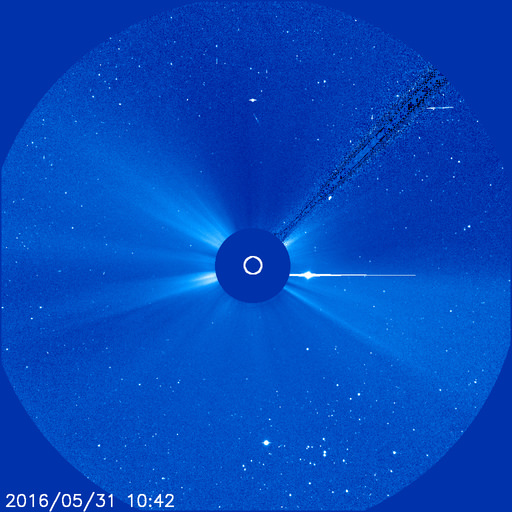

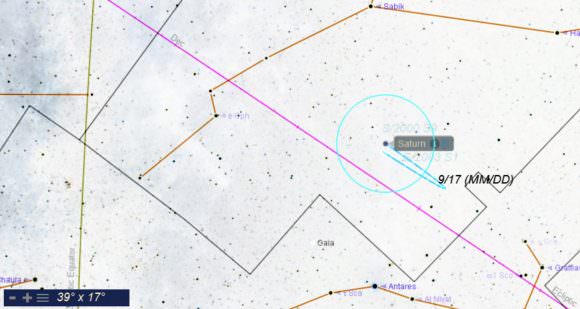

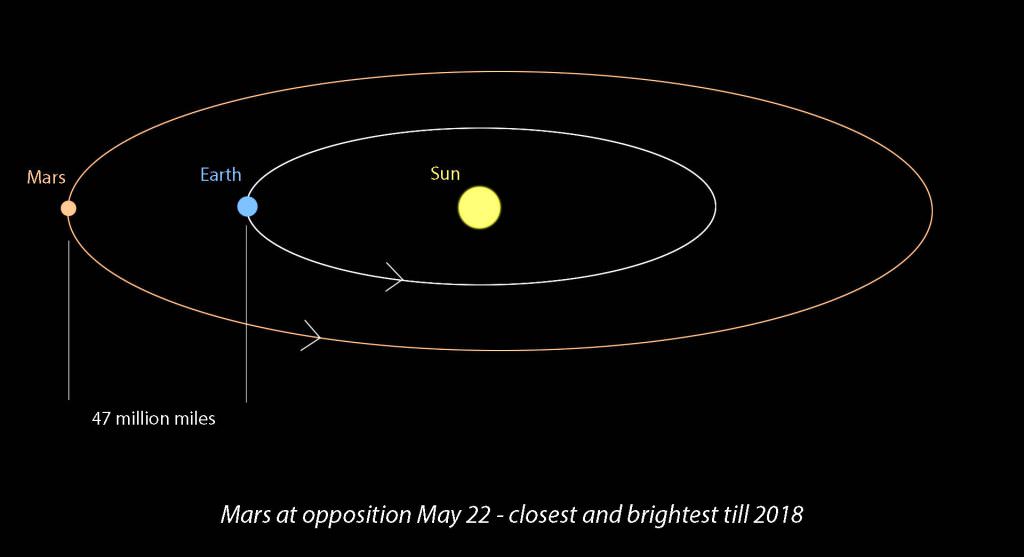

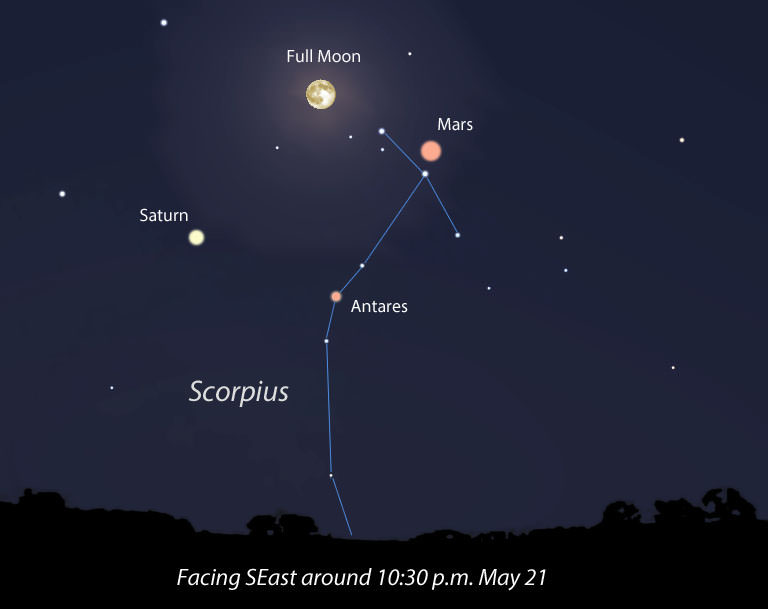

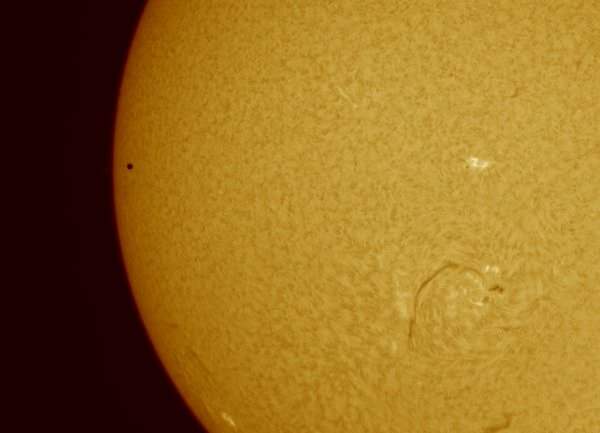

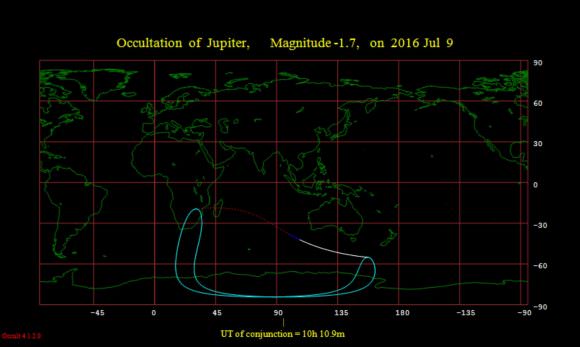

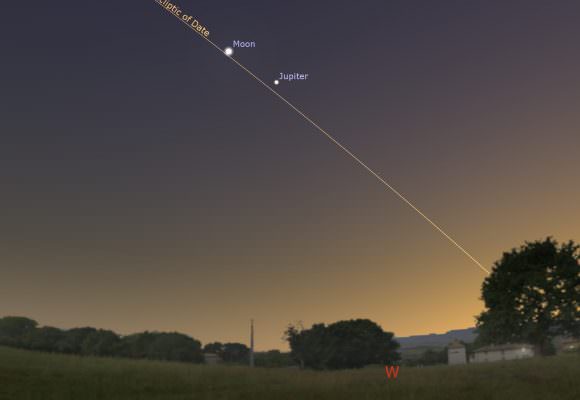

On July 9th, the 5-day old waxing crescent Moon will pass Jupiter. You can see ’em both Saturday night, high in the western sky at dusk. For a very few observers in the southern Indian Ocean and Antarctica, the Moon will actually occult (pass in front of) Jupiter, centered on 10:11 Universal Time (UT). The Moon will be 32% illuminated crescent during the pass, and Jupiter will present a disk 34” across, just over a month past quadrature on June 4th with a current elongation of 60 degrees east of the Sun. Jupiter just passed opposition for 2016 on March 8th, and is now headed towards solar conjunction on the far side of the Sun on September 26th.

2016 Planetary Occultations

This is the first of four occultations of Jupiter by the Moon in 2016; the next occur over subsequent lunations on August 6th, September 2nd and 30th before the relative motions of the Moon and Jupiter carry them apart, not to meet again until October 31st, 2019. And though most observers will miss this weekend’s occultation, we’ll all get a good view of the pairing worldwide. Unfortunately, the view gets successively worse (though more central) for the next few lunations, as the occultations of Jupiter by the Moon occur close to the Sun.

Here’s another reason to celebrate and show off Jupiter at this weekend’s star party: NASA’s Juno spacecraft has just entered orbit around the gas giant world. This is only the second time a mission has orbited Jupiter (the first was Galileo) though lots have performed brief flybys, using the enormous pull of the planet for a gravitational boost en route to elsewhere. Juno is currently the only spacecraft in operation around Jove, and will conduct 36 looping science orbits around the planet before meeting its fiery end in February 2018.

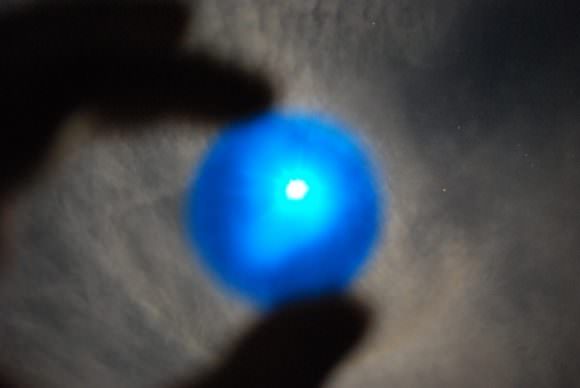

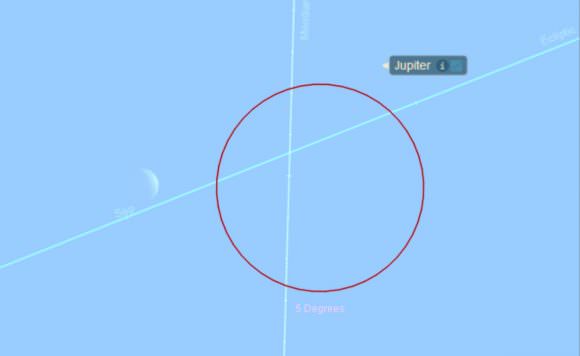

Yay, humans. Here’s another feat of visual athletics you can attempt this weekend: can you spy Jupiter near the waxing crescent Moon… in the daytime? It’s not that tough, if you know exactly where to look. Deep blue skies for maxim contrast are key, and don’t be afraid to cheat a bit and use binoculars or a wide-field DSLR shot to tease bashful Jupiter out of the daytime sky. Your best bet might be to start hunting for Jupiter 30 minutes prior to local sunset. Hey, if the Sun is still above the local horizon, it still counts! We’ve actually managed to nab Jupiter and Venus before sundown at public star parties on occasion, kicking things off a bit early.

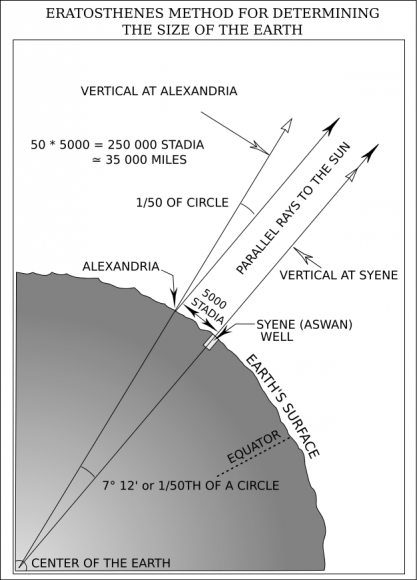

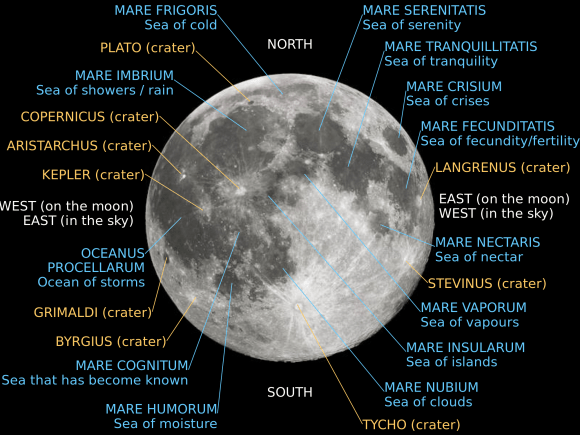

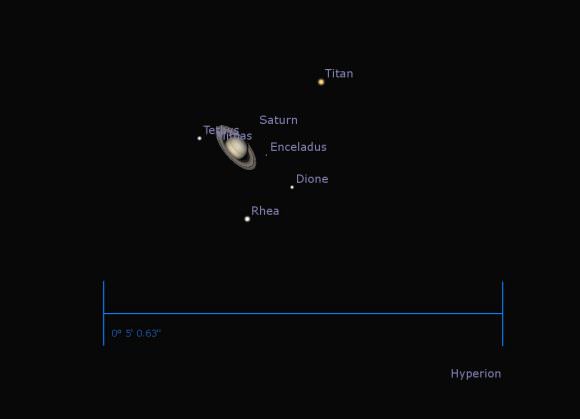

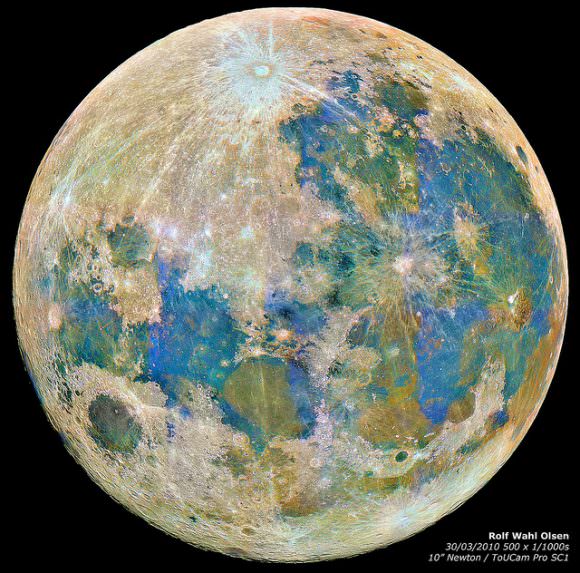

Now for the ‘wow’ factor. The Moon is 3,474 kilometers across, and on average, 400,000 kilometers or 1.25 light seconds distant. Jupiter, at 140,000 kilometers across, is currently 5.9 Astronomical Units (AU) or 880 million kilometers away, 2,200 times more distant at 49 light minutes away. You could fit Jupiter and all of the other planets in the solar system – excluding Saturn’s rings — between the Earth and the Moon… not that you’d want such mayhem, of course. Hey; then, for the very first time in the history of human astronomy, Jupiter could occult our puny Moon…

Occultations are abruptly swift affairs in a glacially slow universe. The leading edge of the Moon moves about 30” a minute, taking 17 seconds to cover the disk of Jove. Follow Jupiter this summer, as it’ll pass just 4′ from Venus in the dusk sky on August 27th.

More to come on that soon. Here’s a final thought: has anyone ever tried to observe a radio occultation of Jupiter by the Moon? It’s certainly possible, as Jupiter is a prominent amateur radio source, crackling in the sky. And hey, the daytime sky thing wouldn’t be an issue…

We’d be thrilled to hear that, against all odds, someone on a remote windswept island or on a ship in the distant Indian Ocean actually managed to catch this weekend’s occultation!