Asteroid 2015 TB145 isn’t the only cosmic visitor paying our planet a trick-or-treat visit over the coming week. With any luck, the Northern Taurid meteor shower may put on a fine once a decade show heading into early November.

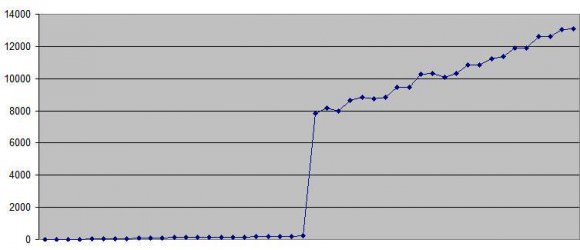

About once a decade, the Northern Taurid meteor stream puts on a good showing. Along with its related shower the Southern Taurids, both are active though late October into early November.

Specifics for 2015

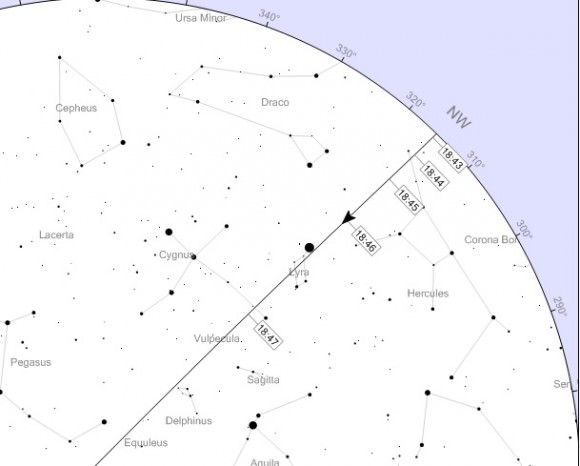

This year sees the Moon reaching Full on Tuesday October 27th, just a few days before Halloween. The Taurid fireballs, however, have a few things going for them that most other showers don’t. First is implied in the name: the Northern Taurids, though typically exhibiting a low zenithal hourly rate of around 5 to 10, are, well, fireballs, and thus the light-polluting Moon won’t pose much of a problem. Secondly, the Taurid meteor stream is approaching the Earth almost directly from behind, meaning that unlike a majority of meteor showers, the Taurids are just as strong in the early evening as the post midnight early morning hours. As a matter of fact, we saw a brilliant Taurid just last night from light-polluted West Palm Beach in Florida, just opposite to the Full Moon and a partially cloudy sky.

In stark contrast to the swift-moving Orionids from earlier this month, expect the Taurid fireballs to trace a brilliant and leisurely slow path across the night sky, moving at a stately 28 kilometre per second (we say stately, as the October Orionids smash into our atmosphere at over twice that speed!)

Ever since the 2005 event, the Northern Taurids seemed to have earned the name as “The Halloween Fireballs” in the meme factory that is the internet. It’s certainly fitting that Halloween should have its very own pseudo-apocalyptic shower. The last good return for the Northern Taurids was 2005-2008, and 2015 may see an upswing in activity as well.

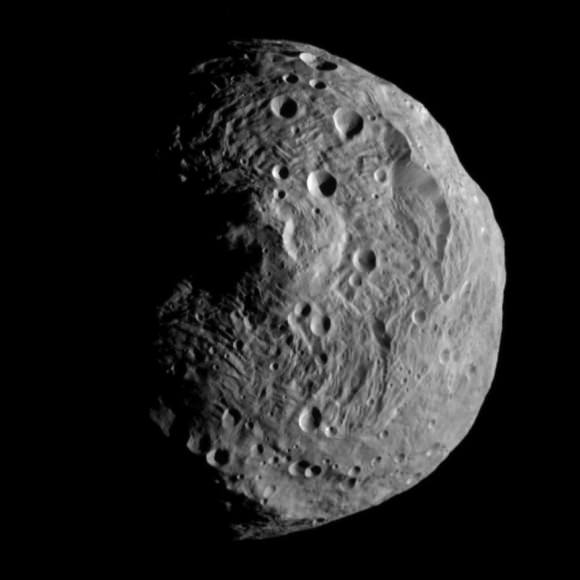

Obviously, something interesting has to be occurring on Comet 2P Encke—the source of the two Taurid meteor streams—to shed the pea-sized versus dust-sized material seen in the Southern and Northern Taurids. With the shortest orbital period 3.3 years of all periodic comets known, the Taurid meteor stream—like Encke itself—follows a shallow path nearly parallel to the ecliptic plane.

Discovered in 1822 by astronomer Johann Encke, Comet 2P Encke has been observed through many perihelion passages over the last few centuries, and passes close to Earth once 33 years, as it last did in 2013.

What constitutes a ‘meteor swarm?’ As with many terms in meteoritics, no hard-and-fast definition of a true ‘meteor swarm’ exists. A meteor storm is generally quoted as having a zenithal hourly rate greater than 1000. Expect activity to be broad over the next few weeks, and the Taurid fireballs always have the capacity to produce the kind of brilliant events captured by security cams and dashboard video cameras that go viral across ye ole Internet.

Watching for fireballs is a thrilling pursuit. These may often leave persistent glowing meteor trails in their wake. We caught the 1998 Leonids from the dark sky deserts of Kuwait, and can attest to the persistence of glowing fireball trails from this intense storm, sometimes for minutes. Again, the 2015 Taurids aren’t expected to reach that level of intensity, though the ratio of fireballs to faint meteors will be enhanced.

The path of the stream isn’t fully understood, and that is where volunteer observations can come in handy. The International Meteor Organization is always looking for reports from skilled observers, as is the American Meteor Society (AMS).

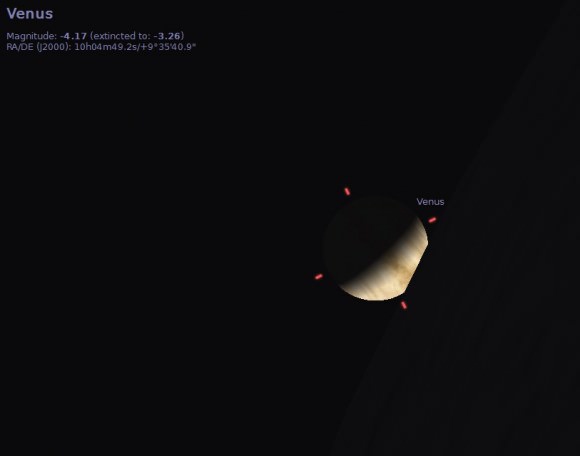

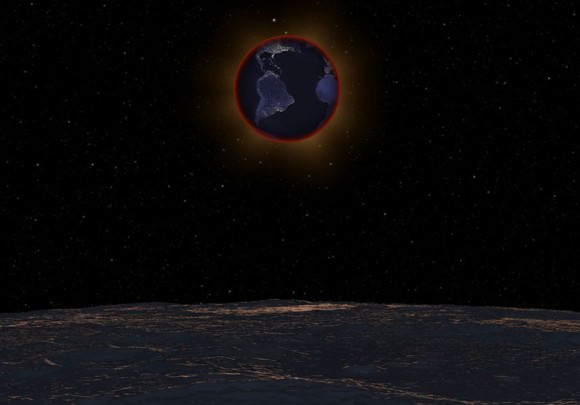

There’s even been evidence for a recorded meteorite strike related to the northern Taurid fireballs back in 2015 on the dark limb of the Moon as well, a rare event indeed.

After a slow summer, Fall meteor shower activity is definitely heating up. And though 2015 is an off year for the November Leonids, we’re now almost midway between the 1998-99 outbursts, and the possibility of another grand meteor storm in the early 2030s. And another obscure wildcard shower known as the Alpha Monocerotids may put on a surprise showing in November 2015 as well…

Bright Meteor 4th November 2013 from Richard Fleet on Vimeo.

More to come on that. Keep watching the skies, and don’t forget to tweet those Northern Taurid fireball sightings and images to #Meteorwatch!

-Got an image of a Northern Taurid fireball? Send ‘em in to Universe Today for our Flickr forum… we may just feature your pic in an after action round up!