Who doesn’t love a Full Moon? Occurring about once a month, they never wear out their welcome. Each one becomes a special event to anticipate. In the summer months, when the Moon rises through the sultry haze, atmosphere and aerosols scatter away so much blue light and green light from its disk, the Moon glows an enticing orange or red.

At Full Moon, we’re also more likely to notice how the denser atmosphere near the horizon squeezes the lunar disk into a crazy hamburger bun shape. It’s caused by atmospheric refraction. Air closest to the horizon refracts more strongly than air near the top edge of the Moon, in effect “lifting” the bottom of the Moon up into the top. Squished light! We also get to see all the nearside maria or “seas” at full phase, while rayed craters like Tycho and Copernicus come into their full glory, looking for all the world like giant spatters of white paint even to the naked eye.

Tomorrow night (August 29), the Full Sturgeon Moon rises around sunset across the world. The name comes from the association Great Lakes Indian groups made between the August moon and the best time to catch sturgeon. Next month’s moon is the familiar Harvest Moon; the additional light it provided at this important time of year allowed farmers to harvest into the night.

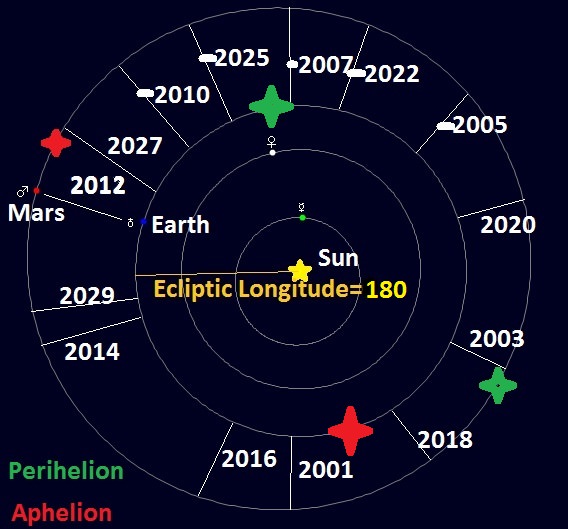

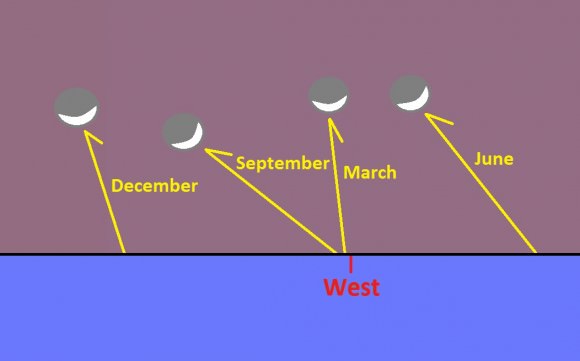

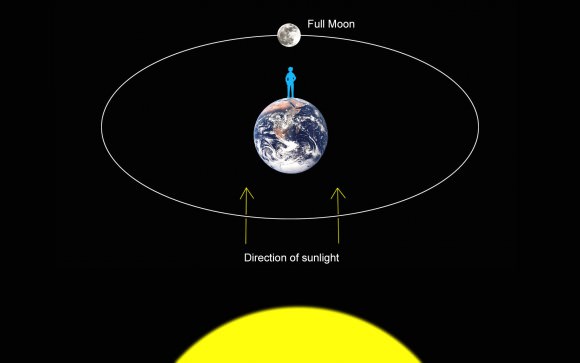

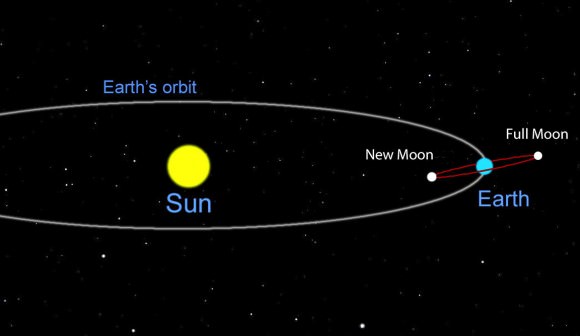

A Full Moon lies opposite the Sun in the sky exactly like a planet at opposition. Earth is stuck directly between the two orbs. As we look to the west to watch the Sun go down, the Moon creeps up at our back from the eastern horizon. Full Moon is the only time the Moon faces Sun directly – not off to one side or another – as seen from Earth, so the entire disk is illuminated.

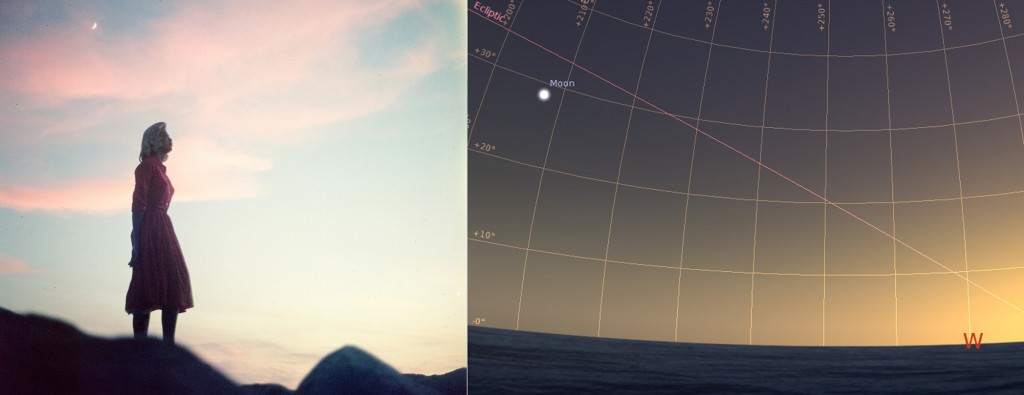

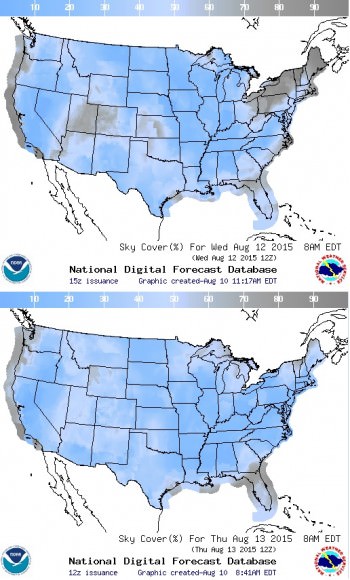

If you’re a moonrise watcher like I am, you’ll want to find a place where you can see all the way down to the eastern horizon tomorrow night. You’ll also need the time of moonrise for your city and a pair of binoculars. Sure, you can watch a moonrise without optical aid perfectly well, but you’ll miss all the cool distortions happening across the lunar disk from air turbulence. Birds have also begun their annual migration south. Don’t be surprised if your glass also shows an occasional winged silhouette zipping over those lunar seas.

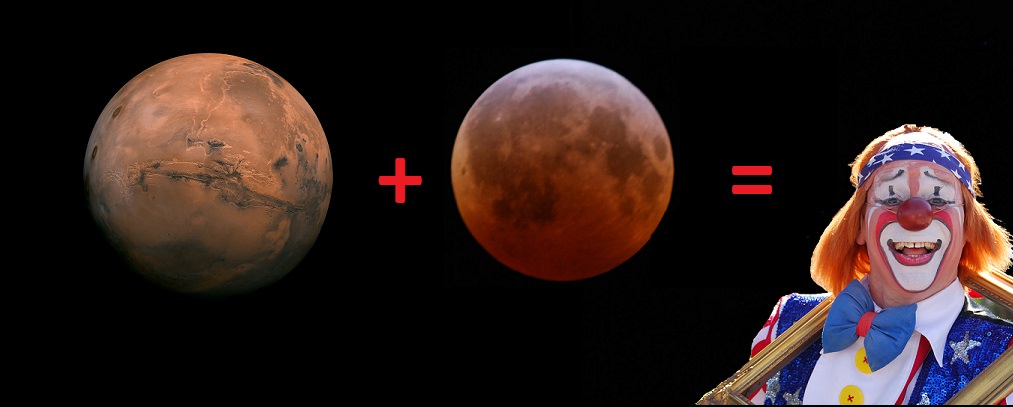

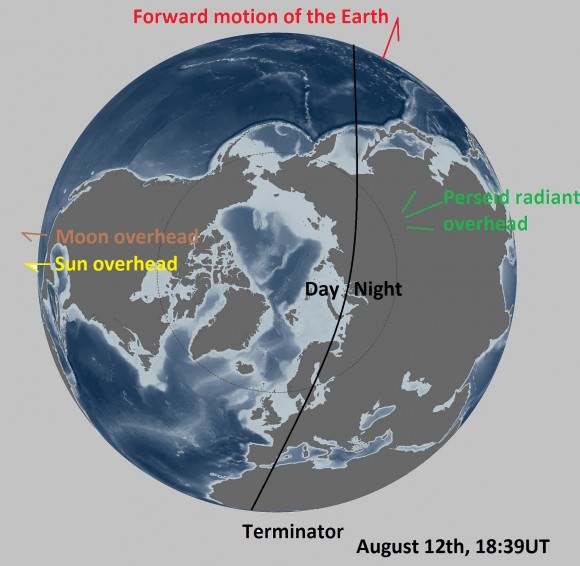

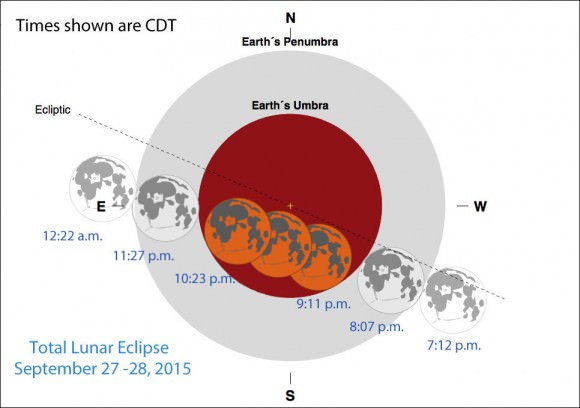

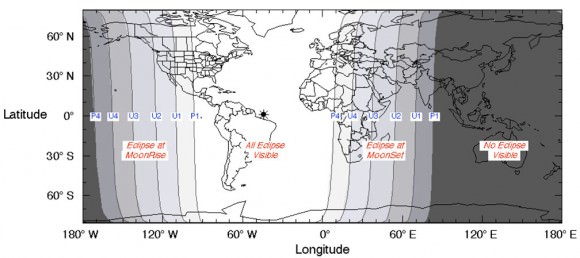

Next month’s Full Moon is very special. A few times a year, the alignment of Sun, Earth and Moon (in that order) is precise, and the Full Moon dives into Earth’s shadow in total eclipse. That will happen overnight Sunday night-Monday morning September 27-28. This will be the final in the current tetrad of four total lunar eclipses, each spaced about six months apart from the other. I think this one will be the best of the bunch. Why?

- Convenient evening viewing hours (CDT times given) for observers in the Americas. Partial eclipse begins at 8:07 p.m., totality lasts from 9:11 – 10:23 p.m. and partial eclipse ends at 11:27 p.m. Those times mean that for many regions, kids can stay up and watch.

- The Moon passes more centrally through Earth’s shadow than during the last total eclipse. That means a longer totality and possibly more striking color contrasts.

- September’s will be the last total eclipse visible in the Americas until January 31, 2018. Between now and then, there will be a total of four minor penumbral eclipses and one small partial. Slim pickings.

Not only will the Americas enjoy a spectacle, but totality will also be visible from Europe, Africa and parts of Asia. For eastern hemisphere skywatchers, the event will occur during early morning hours of September 28. Universal or UT times for the eclipse are as follows: Partial phase begin at 1:07 a.m., totality from 2:11 – 3:23 a.m. with the end of partial phase at 4:27 a.m.

We’ll have much more coverage on the upcoming eclipse in future articles here at Universe Today. I hope this brief look will serve to whet your appetite and help you anticipate what promises to be one of the best astronomical events of 2015.