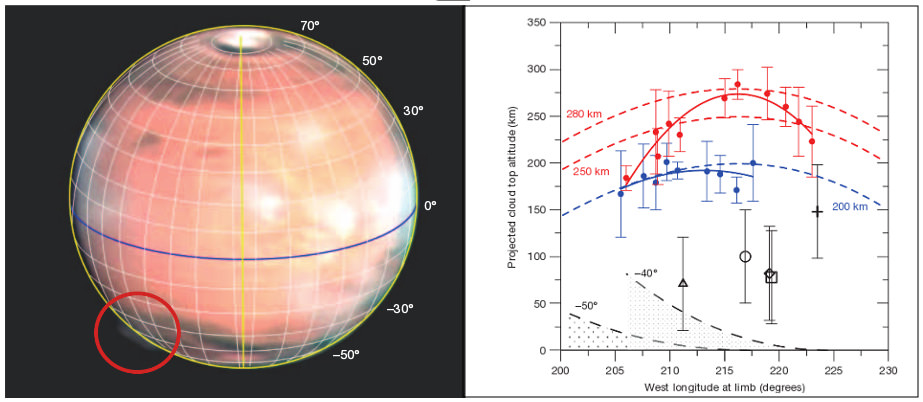

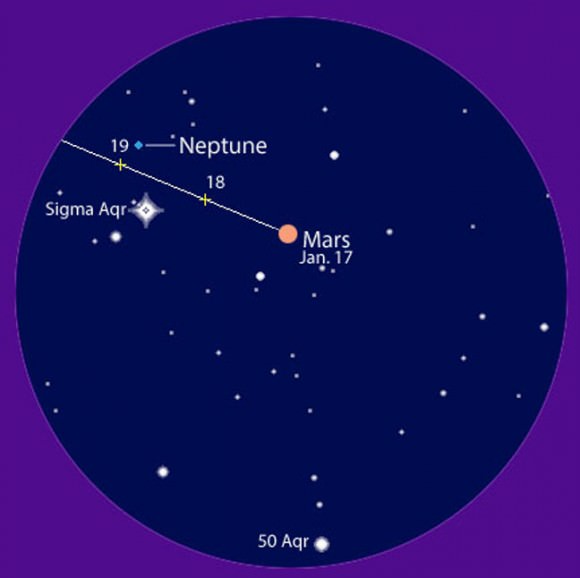

In March 2012, amateur astronomers began observing unusual clouds or plumes along the western limb of the red planet Mars. The plumes, in the southern hemisphere rose to over 200 kilometers altitude persisting for several days and then reappeared weeks later.

So a group of astronomers from Spain, the Netherlands, France, UK and USA have now reported their analysis of the phenomena. Their conclusions are inconclusive but they present two possible explanations.

Mars and mystery are synonymous. Among Martian mysteries, this one has persisted for three years. Our own planet, much more dynamic than Mars, continues to raise new questions and mysteries but Mars is a frozen desert. Frozen in time are features unchanged for billions of years.

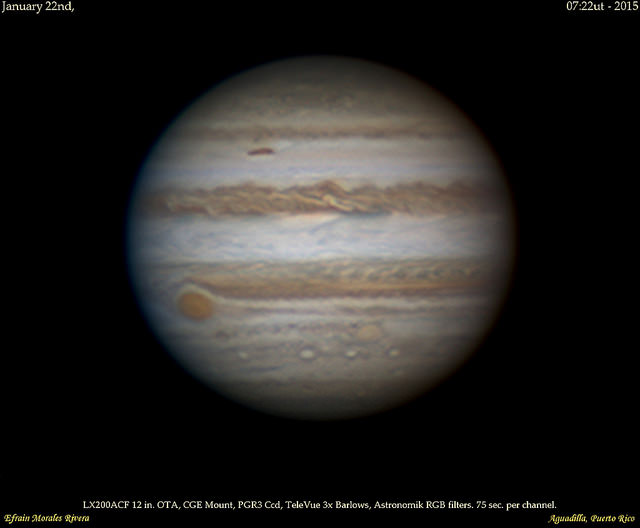

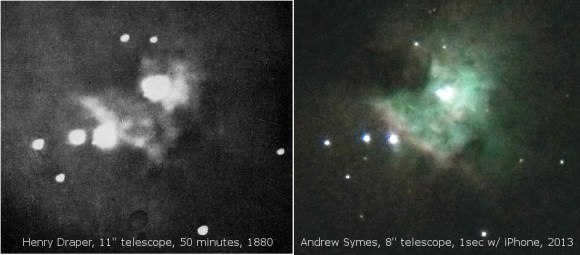

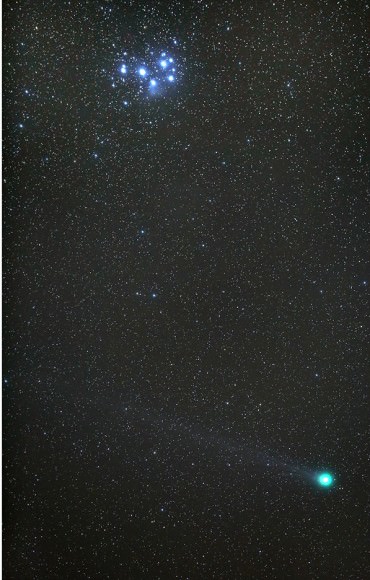

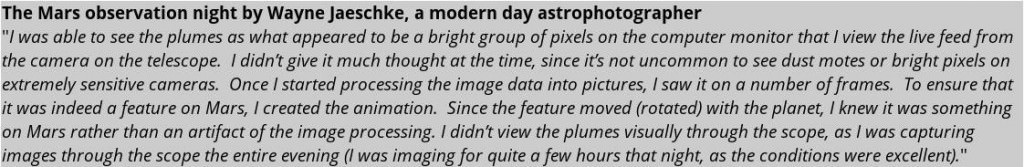

In March 2012, the news of the observations caught the attention of Universe Today contributing writer Bob King. Reported on his March 22nd 2012 AstroBob blog page, the plumes or clouds were clear to see. The amateur observer, Wayne Jaeschke used his 14 inch telescope to capture still images which he stitched together into an animation to show the dynamics of the phenomena.

Now on February 16 of this year, a team of researchers led by Agustín Sánchez-Lavega of the University of the Basque Country in Bilbao, Spain, published their analysis in the journal Nature of the numerous observations, presenting two possible explanations. Their work is entitled: “An Extremely high-altitude plume seen at Mars morning terminator.”

Now on February 16 of this year, a team of researchers led by Agustín Sánchez-Lavega of the University of the Basque Country in Bilbao, Spain, published their analysis in the journal Nature of the numerous observations, presenting two possible explanations. Their work is entitled: “An Extremely high-altitude plume seen at Mars morning terminator.”

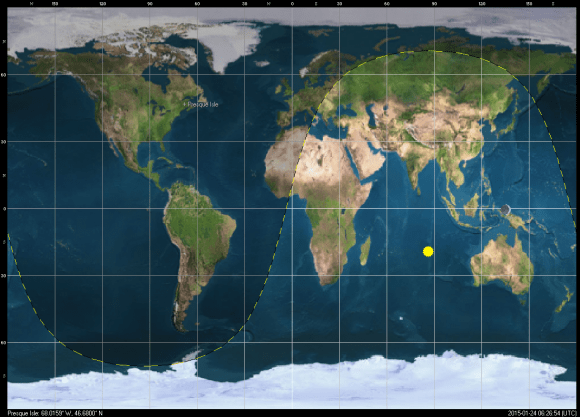

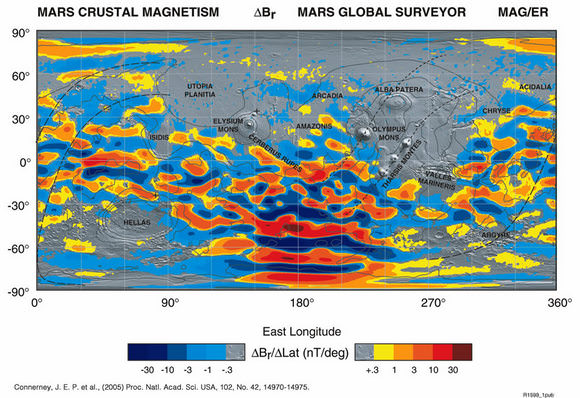

The phenomena occurred over the Terra Cimmeria region centered at 45 degree south latitude. This area includes the tiger stripe array of magnetic fields emanating from concentrations of ferrous (iron) ore deposits on Mars; discovered by the Mars Global Surveyor magnetometer during low altitude aerobraking maneuvers at the beginning of the mission in 1998. Auroral events have been observed over this area from the interaction of the Martian magnetic field with streams of energetic particles streaming from the Sun. Sánchez-Lavega states that if these plumes are auroras, they would have to be over 1000 times brighter than those observed over the Earth.

The researchers also state that another problem with this scenario is the altitude. Auroras over Mars in this region have been observed up to 130 km, only half the height of the features. In the Earth’s field, aurora are confined to ionospheric altitudes – 100 km (60 miles). The Martian atmosphere at 200 km is exceedingly tenuous and the production of persistent and very bright aurora at such an altitude seems highly improbable.

The duration of the plumes – March 12th to 23rd, eleven days (after which observations of the area ended) and April 6th to 16th – is also a problem for this explanation. Auroral arcs on Earth are capable of persisting for hours. The Earth’s magnetic field functions like a capacitor storing charged particles from the Sun and some of these particles are discharged and produced the auroral oval and arcs. Over Mars, there is no equivalent capacitive storage of particles. Auroras over Mars are “WYSIWYG” – what you see is what you get – directly from the Sun. Concentrated solar high energy streams persisting for this long are unheard of.

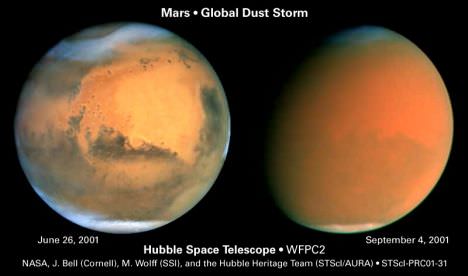

The second explanation assessed by the astronomers is dust or ice crystals lofted to this high altitude. Again the altitude is the big issue. Martian dust storms will routinely lift dust to 60 km, still only one-third the height of the plumes. Martian dust devils will lift particles to 20 km. However, it is this second explanation involving ice crystals – Carbon Dioxide and Water – that the researchers give the most credence. In either instance, the particles must be concentrated and their reflectivity must account for the total brightness of the plumes. Ice crystals would be more easily transported to these heights, and also would be most highly reflective.

The paper also considered the shape of the plumes. The remarkable quality of modern amateur astrophotography cannot be overemphasized. Also the duration of the plumes was considered. By local noon and thereafter they were not observed. Again, the capabilities tendered by ground-based observations were unique and could not be duplicated by the present set of instruments orbiting Mars.

Still too many questions remain and the researchers state that “both explanations defy our present understanding of the Mars’ upper atmosphere.” By March 20th and 21st, the researchers summarized that at least 18 amateur astronomers observed the plume using from 20 to 40 cm telescopes (8 to 16 inch diameter) at wavelengths from blue to red. At Mars, the Mars Color Imager on MRO (MARCI) could not detect the event due to the 2 hour periodic scans that are compiled to make global images.

Of the many ground observations, the researchers utilized two sets from the venerable astrophotographers Don Parker and Daiman Peach. While observations and measurements were limited, the researchers analysis was exhaustive and included modeling assuming CO2, Water and dust particles. The researchers did find a Hubble observation from 1997 that compared favorably with the 2012 events and likewise modeled that event for comparison. However, Hubble results provided a single observation and the height estimate could not be narrowly constrained.

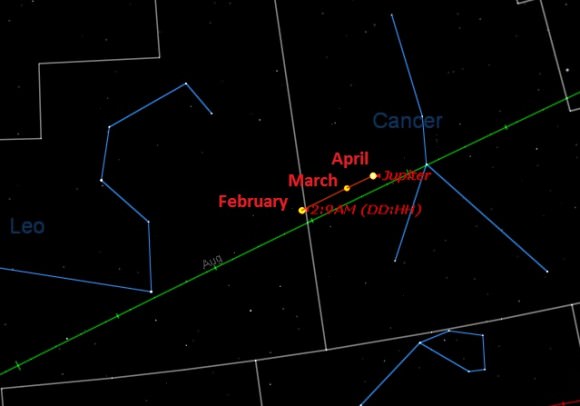

Explanation of these events in 2012 are left open-ended by the research paper. Additional observations are clearly necessary. With increased interest from amateurs and continued quality improvements plus the addition of the Maven spacecraft suite of instruments plus India’s Mars Orbiter mission, observations will eventually be gained and a Martian mystery solved to make way for yet another.

References:

An Extremely High-Altitude Plume seen at Mars’ Morning Terminator, Journal Nature, February 16, 2015

Amateur astronomer photographs curious cloud on Mars, AstroBob, March 22, 2012