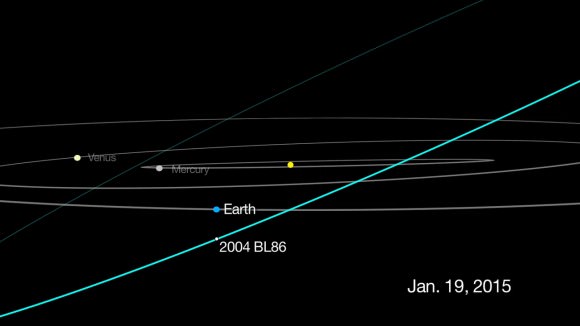

A lot of asteroids pass near Earth every year. Many are the size of a house, make close flybys and zoom out of the headlines. 2004 BL86 is a bit different. On Monday evening January 26th, it will become the largest asteroid to pass closest to Earth until 2027 when 1999 AN10 will approach within one lunar distance.

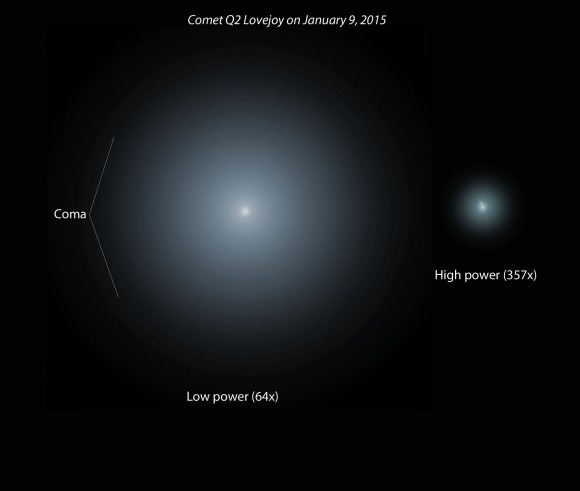

Big is good. 2004 BL86 checks in at 2,230 feet (680-m) wide or nearly half a mile. Add up its significant size and relatively close approach – 745,000 miles (1.2 million km) – and something wonderful happens. This newsy space rock is expected to reach magnitude +9.0, bright enough to see in a 3-inch telescope or even large binoculars.

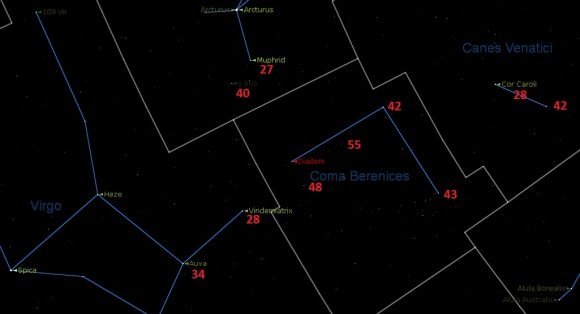

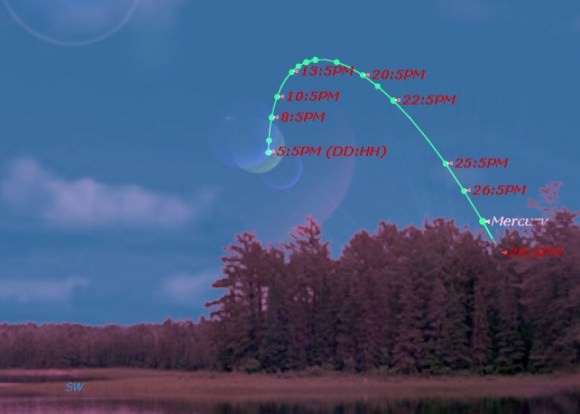

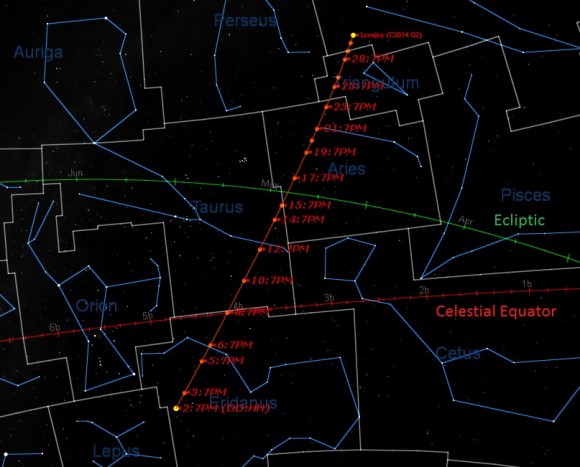

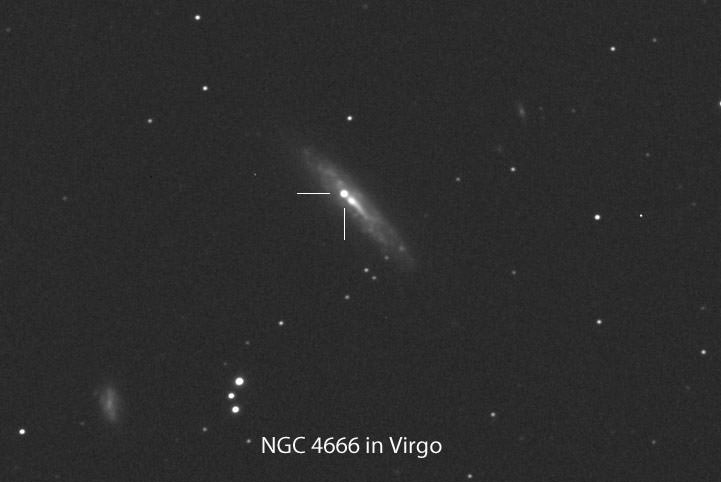

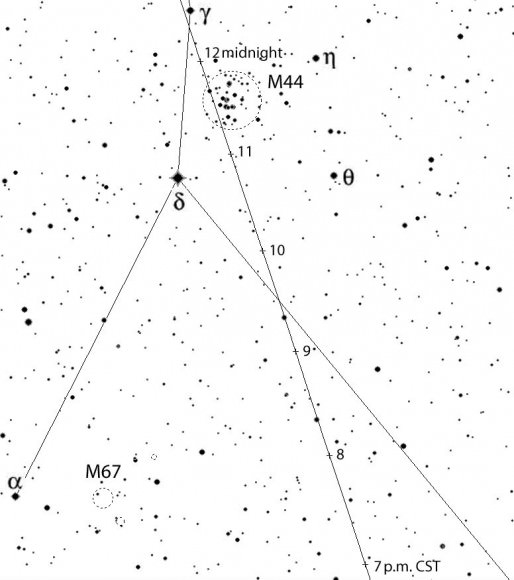

This is a rare opportunity then to see an Earth-approaching asteroid so easily. All you need is a good map as 2004 BL86 will be zipping along at two arc seconds per second or two degrees (four Moon diameters) per hour. That means you’ll see it move in real time like a slow satellite inching its way across the sky. Cool!

As you can see from its name, 2004 BL86 was discovered 11 years ago in 2004 by the Lincoln Near-Earth Asteroid Research (LINEAR), an MIT Lincoln Laboratory program to track near-Earth objects funded by the U.S. Air Force and NASA. As of September 15, 2011, the search has swept up 2,423 new asteroids and 279 new comets.

All asteroids with well-known orbits receive a number. The first asteroid, 1 Ceres, was discovered in 1801. The 4,150th asteroid, 4150 Starr and named for the Beatles’ Ringo Starr, was found in 1984. 2004 BL86 will likely be the highest-numbered asteroid any of us will ever see. How does 357,439 sound to you?

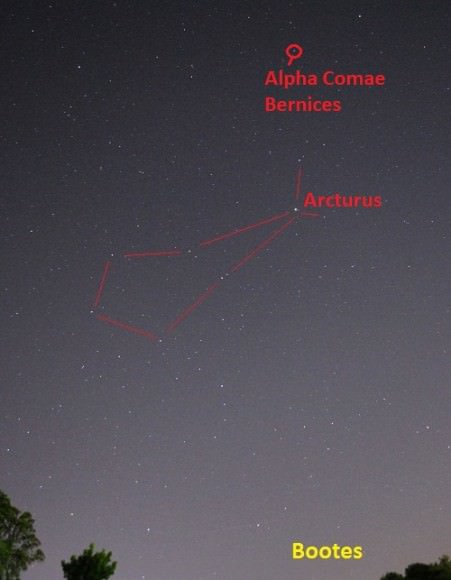

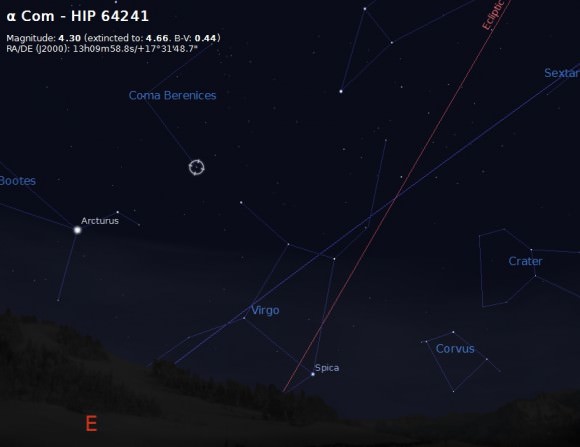

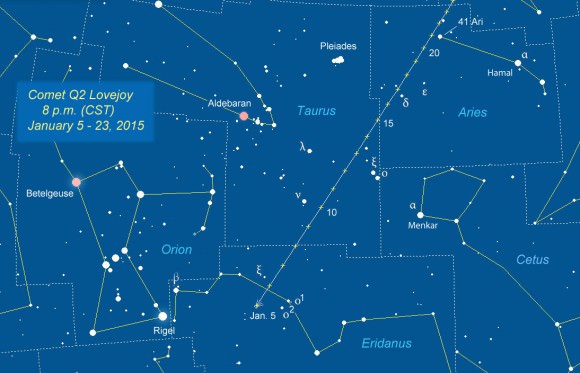

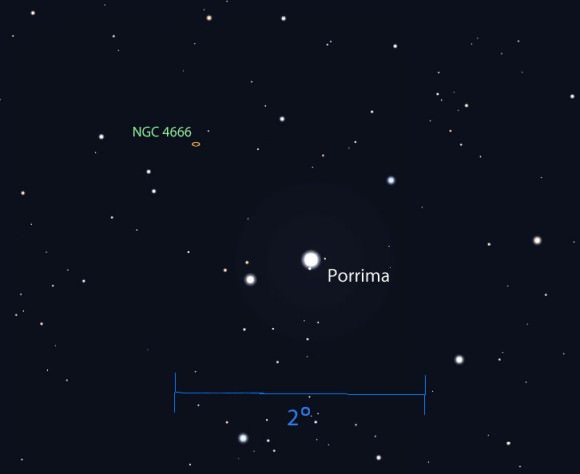

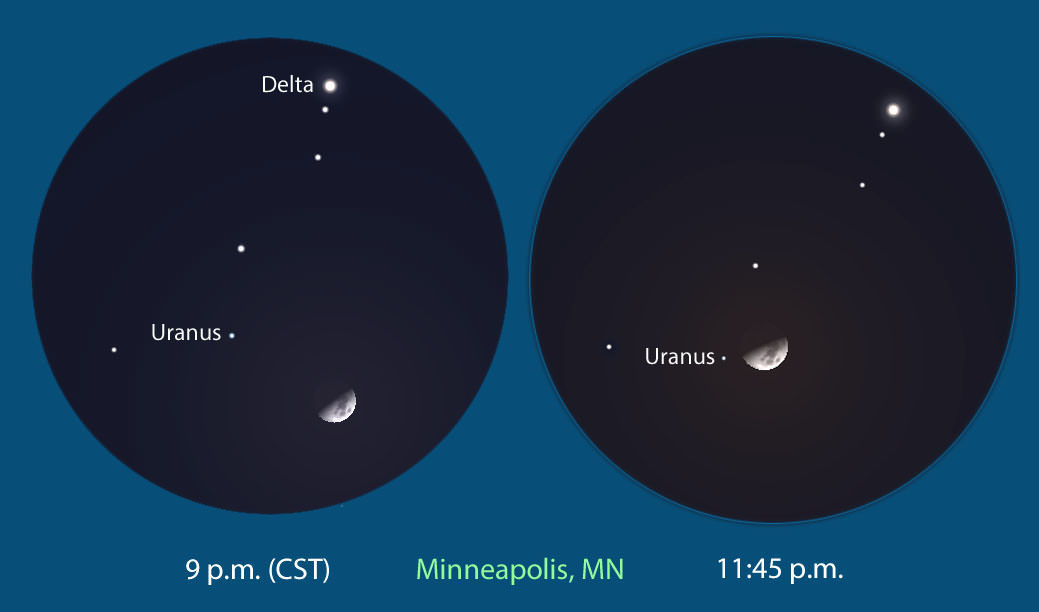

Observers in the Americas, Europe and Africa will have the best seats for viewing the asteroid, which will shine brightest between 7 p.m. and midnight CST from a comfortably high perch in Cancer the Crab not far from Jupiter. The half-moon will also be out but over in the western sky, so shouldn’t get in the way of seeing our speedy celeb.

Not only will 2004 BL86 pass near a few fairly bright stars but the Beehive Cluster (M44) will temporarily gain a new member between 11 p.m. and midnight as the asteroid buzzes across the well-known star cluster.

“Monday, January 26 will be the closest asteroid 2004 BL86 will get to Earth for at least the next 200 years,” said Don Yeomans, who’s retiring as manager of NASA’s Near Earth Object Program Office at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, after 16 years in the position.

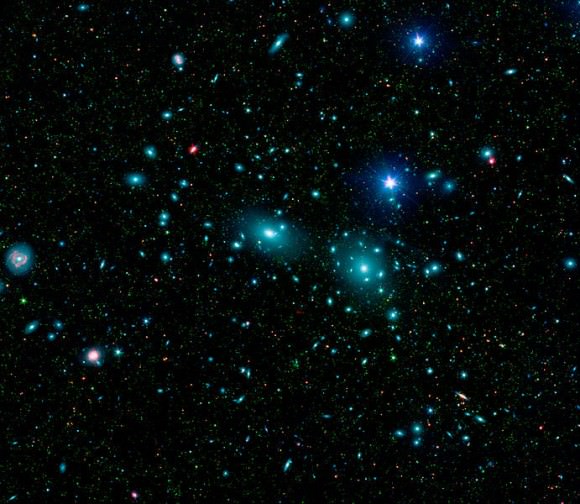

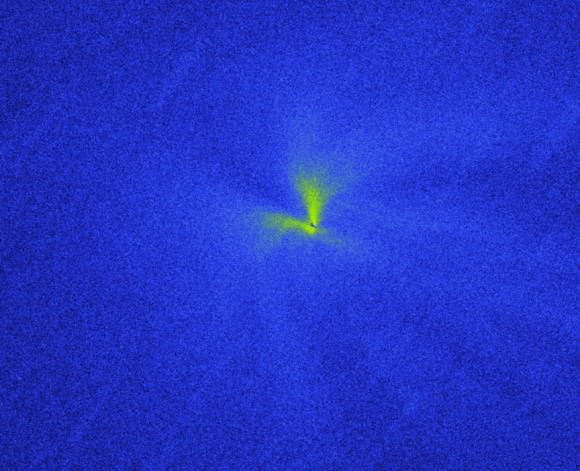

To learn more about the space rock and acquire close-ups of its surface, NASA’s Deep Space Network antenna at Goldstone, California, and the Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico will attempt to ping the asteroid with microwaves to create radar-generated images of the asteroid during the days surrounding its closest approach to Earth.

“When we get our radar data back the day after the flyby, we will have the first detailed images,” said radar astronomer Lance Benner of JPL, principal investigator for the Goldstone radar observations of the asteroid. “At present, we know almost nothing about the asteroid, so there are bound to be surprises.”

While 2004 BL86 will be brightest Monday night, that’s not the only time amateur astronomers might see it. It comes into view for southern hemisphere observers around magnitude +13 on Jan. 24 and leaves the scene at a similar brightness high in the northeastern sky in the northern hemisphere on the 29th. If you use a star-charting program like Starry Night, Guide, MegaStar and others, you can get updated orbital element packages HERE. Just select your program and download the Observable Unusual Minor Planets file. Open it in your software and create maps for the entire apparition.

One last observing tip before you go your own way. Close asteroids will sometimes be a little bit off a particular track depending on your location. Not much but enough that I recommend you scan not just the single spot where you expect to see it but also nearby in the field of view. If you see a “star” on the move – that’s it.

As always, Dr. Gianluca Masi, Italian astrophysicist, will share his live coverage of the event beginning at 1:30 p.m. (19:30 UT) Jan. 26th.

Let us know if you see our not-so-little cosmic friend. Good luck!