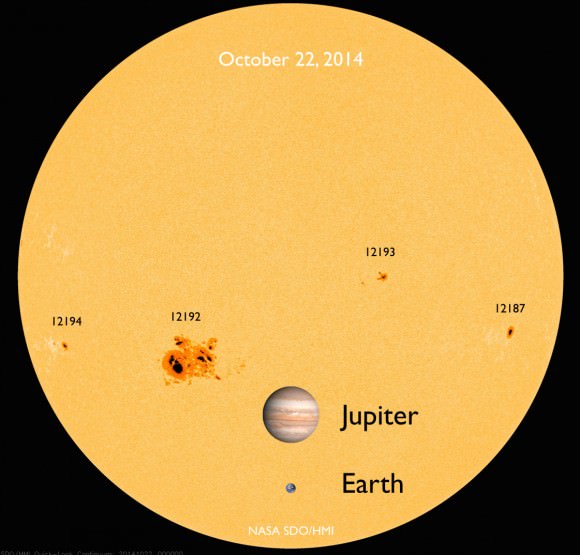

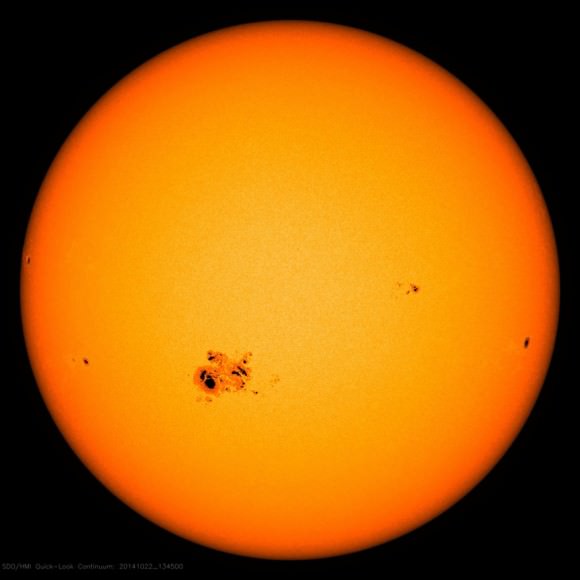

Missing the planets this month? With Mars receding slowly to the west behind the Sun at dusk, the early evening sky is nearly devoid of planetary action in the month of November 2014. Stay up until about midnight local, however, and brilliant Jupiter can be seen rising to the east. Well placed for northern hemisphere viewers in the constellation Leo, Jupiter is about to become a common fixture in the late evening sky as it heads towards opposition next year in early February.

An interesting phenomenon also reaches its climax, as we make the first of a series of passes through the ring plane of Jupiter’s moons this week on November 8th, 2014. This means that we’re currently in a season where Jupiter’s major moons not only pass in front of each other, but actually eclipse and occult one another on occasion as they cast their shadows out across space.

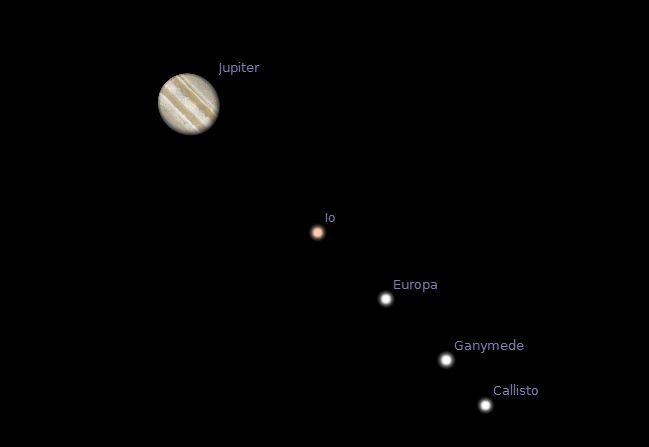

These types of events are challenging but tough to see, owing to the relatively tiny size of Jupiter’s moons. Followers of the giant planet are familiar with the ballet performed by the four large Jovian moons of Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto. This was one of the first things that Galileo documented when he turned his crude telescope towards Jupiter in late 1609. The shadows the moons cast back on the Jovian cloud tops are a familiar sight, easily visible in a small telescope. Errors in the predictions for such passages provided 17th century Danish astronomer Ole Rømer with a way to measure the speed of light, and handy predictions of the phenomena for Jupiter’s moons can be found here.

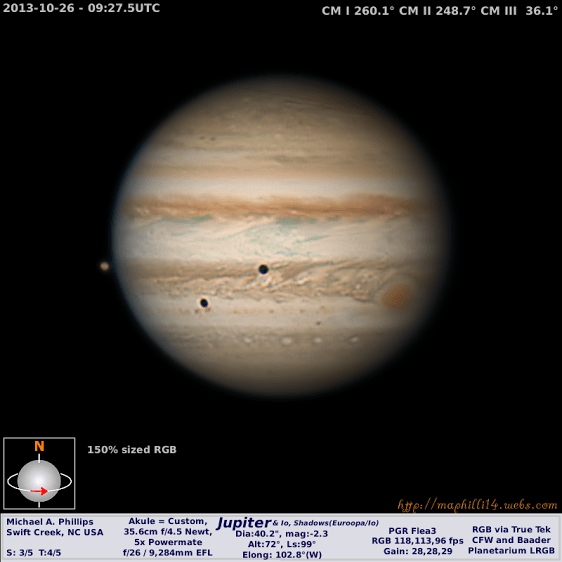

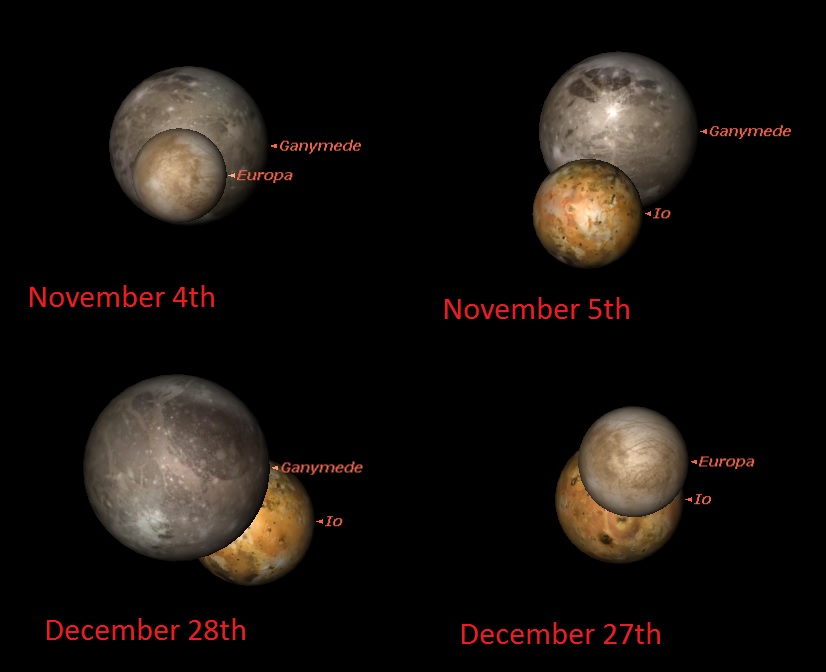

Mutual occultations and eclipses of the Jovian moons are much tougher to see. The moons range in size from 3,121 km (Europa) to 5,262 km (Ganymede), which translates to 0.8”-1.7” in apparent diameter as seen from the Earth. This means that the moons only look like tiny +6th magnitude stars even at high magnification, though sophisticated webcam imagers such as Michael Phillips and Christopher Go have managed to actually capture disks and tease out detail on the tiny moons.

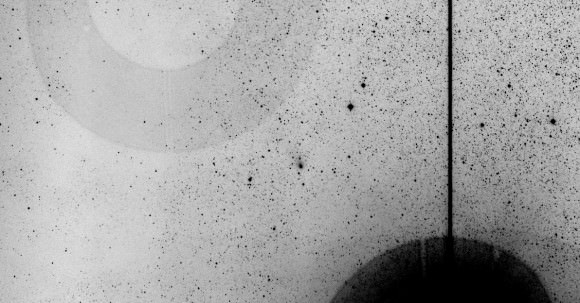

What is most apparent during these mutual events is a slow but steady drop in combined magnitude, akin to that of an eclipsing variable star such as Algol. Running video, Australian astronomer David Herald has managed to document this drop during the 2009 season (see the video above) and produce an effective light curve using LiMovie.

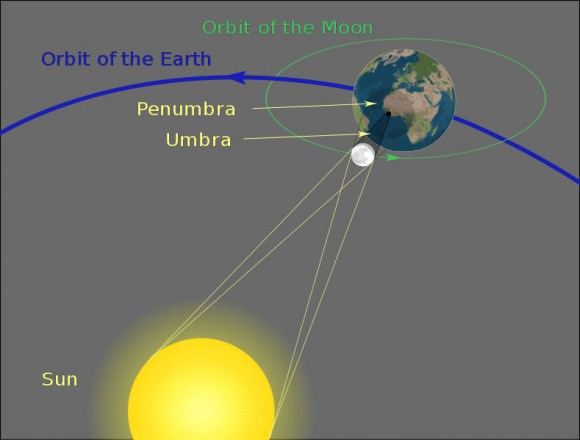

Such events occur as we cross through the orbital planes of Jupiter’s moons. The paths of the moons do not stray more than one-half of a degree in inclination from Jupiter’s equatorial plane, which itself is tilted 3.1 degrees relative to the giant planet’s orbit. Finally, Jupiter’s orbit is tilted 1.3 degrees relative to the ecliptic. Plane crossings as seen from the Earth occur once every 5-6 years, with the last series transpiring in 2009, and the next set due to begin around 2020. Incidentally, the slight tilt described above also means that the outermost moon Callisto is the only moon that can ‘miss’ Jupiter’s shadow on in-between years. Callisto begins to so once again in July 2016.

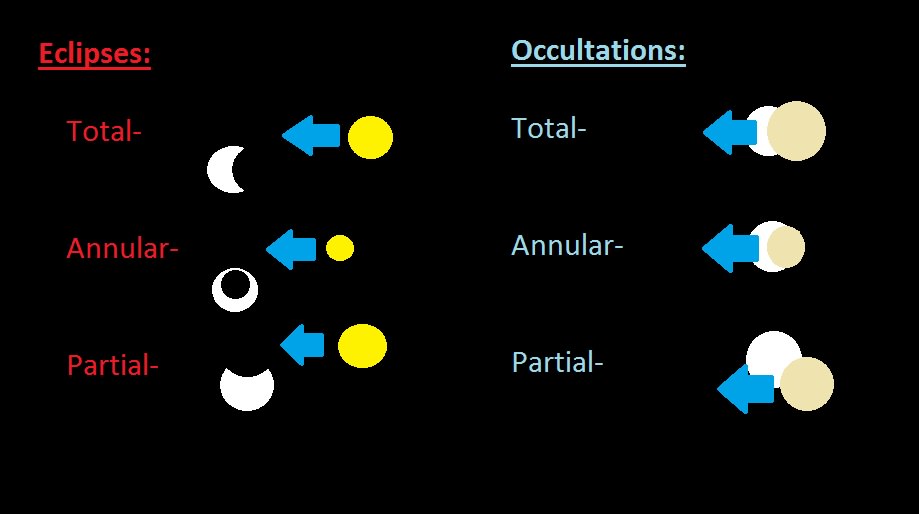

Mutual events for the four Galilean moons come in six different flavors:

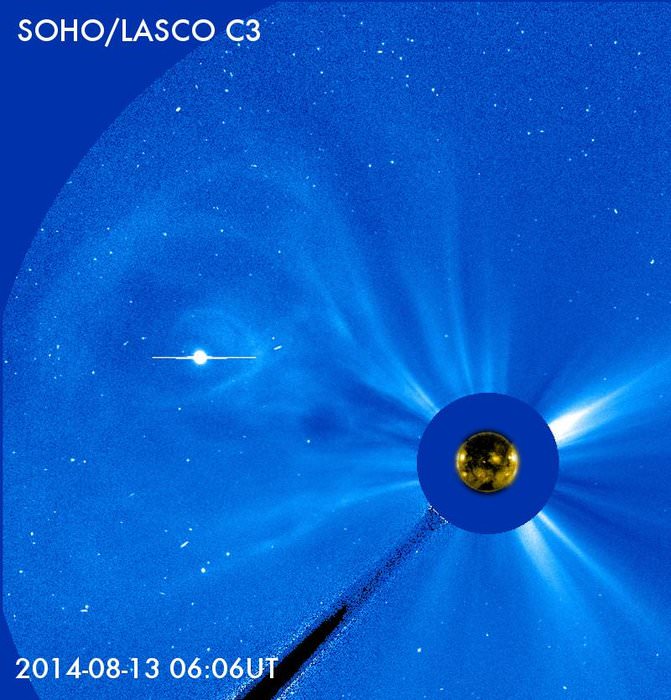

This month, Jupiter reaches western quadrature on November 14th, meaning that Jupiter and its moons sit 90 degrees from the Sun and cast their shadows far off to the side as seen from the Earth. This margin slims as the world heads towards opposition on February 6th, 2015, and Jupiter once again joins the evening lineup of planets.

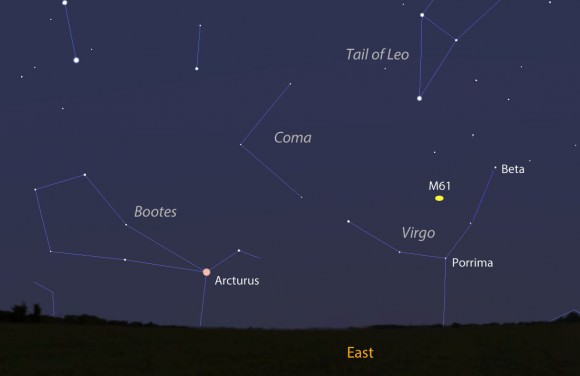

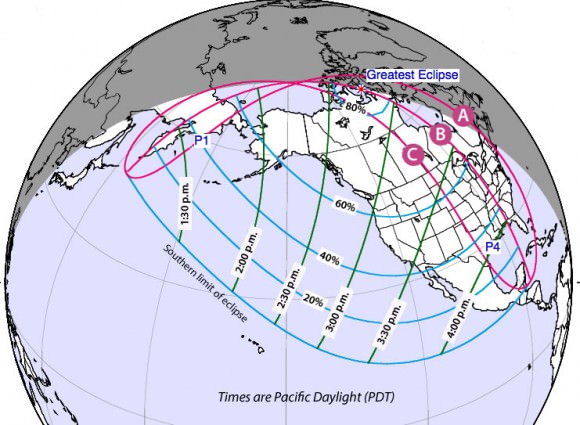

Early November sees Jupiter rising around 1:00 AM local, about six hours prior to sunrise. Jupiter is also currently well placed for northern hemisphere viewers crossing the constellation Leo.

The Institut de Mécanique Céleste et de Calcul des Éphémérides (IMCCEE) based in France maintains an extensive page following the science and the circumstances for the previous 2009 campaign and the ongoing 2015 season.

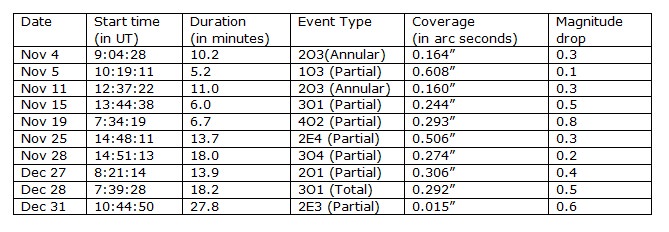

We also distilled down a table of key events for North America coming up through November and December:

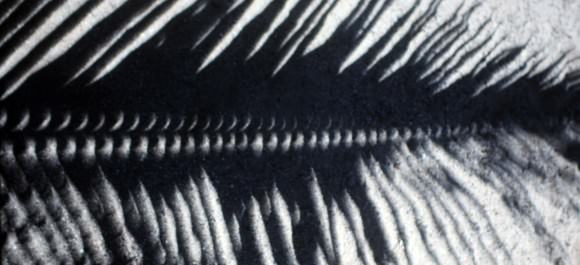

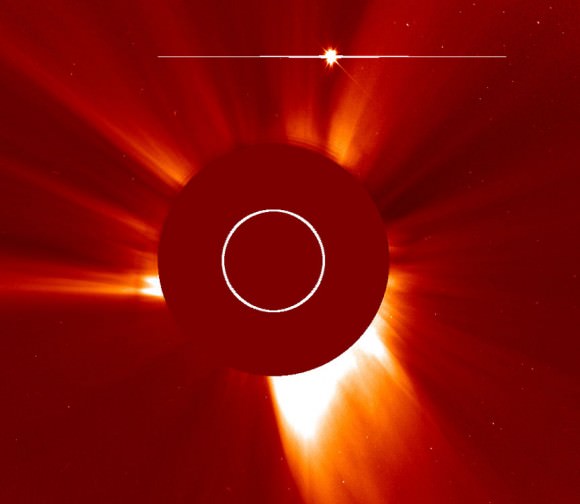

Fun fact: we also discovered during our research for this piece that these events can also produce a total solar eclipse very similar to the near perfect circumstances enjoyed on the Earth via our Moon:

Note that this season also produces another triple shadow transit on January 24th, 2015.

Observing and recording these fascinating events is as simple as running video at key times. If you’ve imaged Jupiter and its moons via our handy homemade webcam method, you also possess the means to capture and analyze the eclipses and occultations of Jupiter’s moons.

Good luck, and let us know of your tales of astronomical tribulation and triumph!