47 Tucanae… the Coal Sack… Magellanic Clouds large and small… sure, it can be argued that the southern hemisphere sky has got all the “good stuff.” We’ve journeyed below the equator half a dozen times ourselves and we always make it a point to carry our trusty Canon 15x 45 image stabilized binocs – or track someone down with a serious ‘scope – even when astronomy isn’t the main focus of our particular away mission.

But did you know that you can glimpse one of the jewels of the southern hemisphere sky from mid-northern latitudes in May and June?

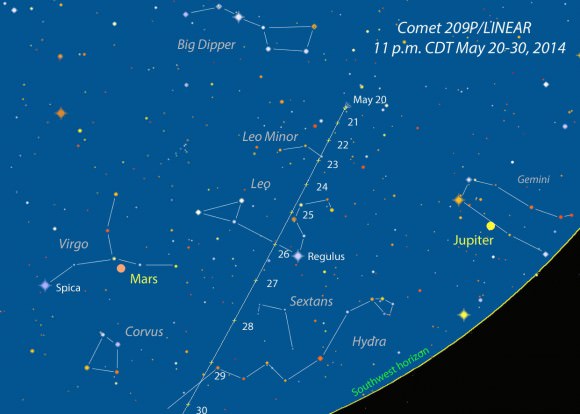

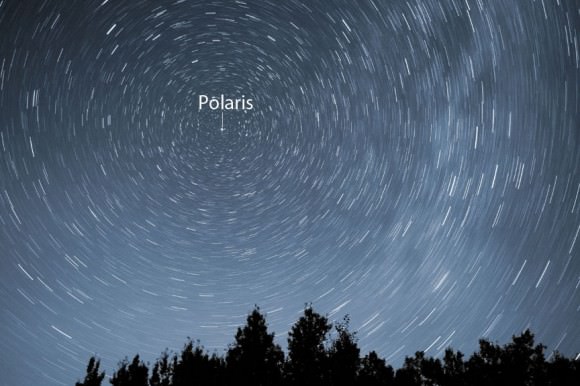

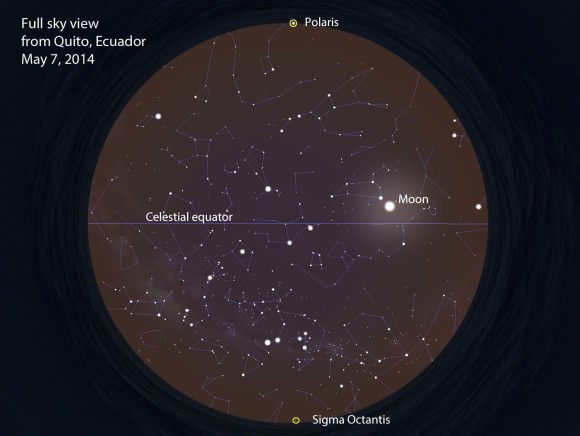

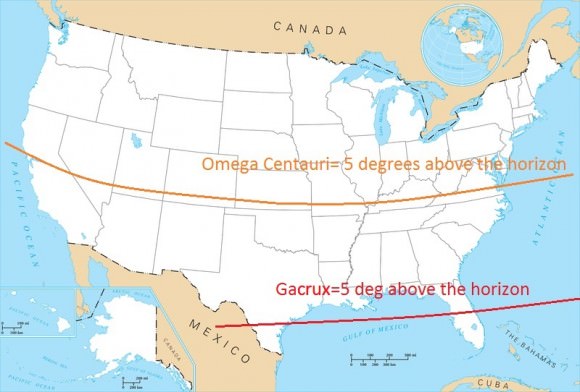

We’re talking about Omega Centauri in the constellation Centaurus. At a declination of -47 degrees south, it clears 5 degrees above the horizon as seen from around 37 degrees north, which corresponds to the latitudes of Richmond Virginia, Wichita Kansas and Sacramento, California in the United States and Seville Spain, Adana Turkey and Seoul South Korea worldwide.

In fact, it would be a fun project to see just how far north you could spot Omega Centauri from… located at right ascension 13 hours 26 minutes and declination -47 29’, Omega Centauri would theoretically juuusst clear the southern horizon at 52 degrees north, well into Canada… but has anyone caught sight of it that far north?

There’s evidence that Ptolemy knew of and recorded Omega Centauri in his Almagest as far back as 150 A.D. It was erroneously misidentified as a star over the centuries, hence the “Omega” designation. It was also too low in the southern sky to be included Charles Messier’s Paris-based catalog of deep sky objects, though it would’ve easily have made the cut had it been located farther north. Omega Centauri was first described by Edmond Halley in 1677 and made its catalog debut in 1746 when astronomer Jean-Philippe de Cheseaux listed it along with 21 other southern sky nebulae.

Shining at magnitude +4, Omega Centauri actually covers a section of sky slightly larger than the apparent size of a Full Moon and is an easy naked eye object from the southern hemisphere. From south of the equator we can easily pick out Omega Centauri from a dark sky site. On a recent trip to the Florida Keys, we could easily detect Omega Centauri riding high to the south over the Straits of Florida at local midnight. In fact, Arthur Upgreen muses in his fantastic book Many Skies just what Florida skies would look like if Omega Centauri were much closer to Earth, filling up the southern horizon scene.

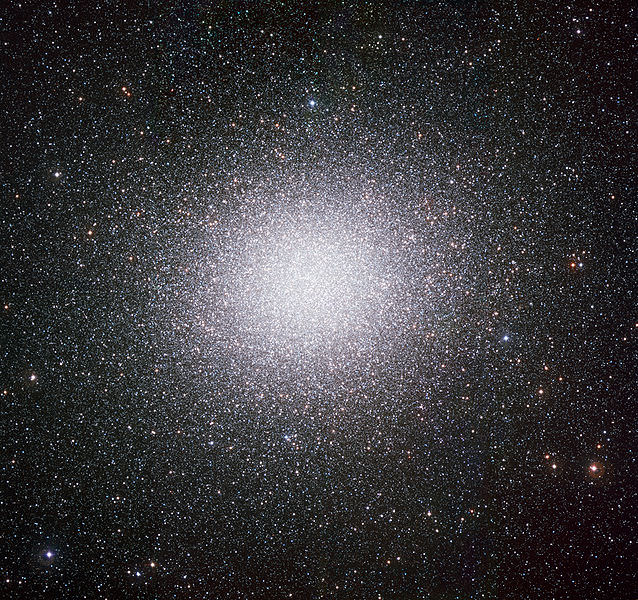

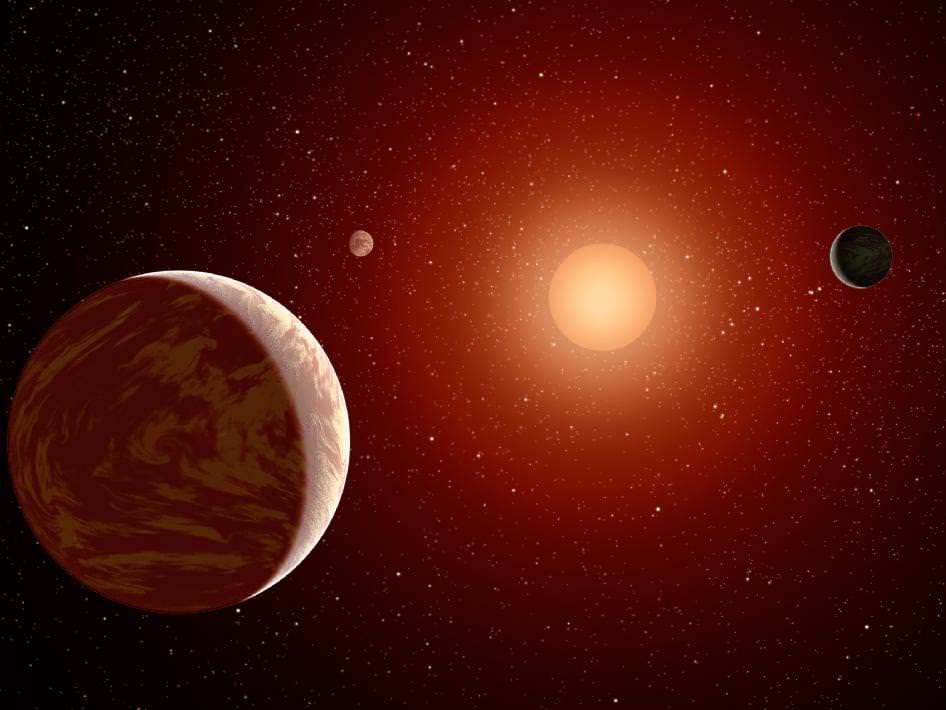

Now for the wow factor of what you’re seeing. The largest of the 150-odd known globular clusters associated with our Milky Way Galaxy, Omega Centauri is almost 16,000 light years distant and weighs in at an estimated 4 million solar masses. Globular clusters are ancient structures and Omega Centauri contains millions of Population II stars dating from an age of about 12 billion years ago. The density at the core of the cluster is equal to a star per every 1/10th of a light year apart, and any planets orbiting said stars would host truly dazzling skies.

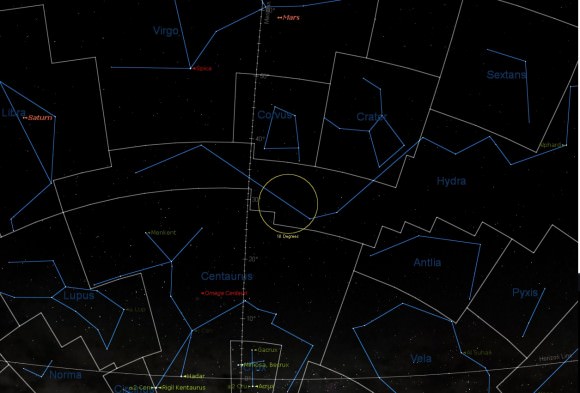

The bright star Spica (Alpha Virginis) in the constellation of Virgo the Virgin makes a good guide to find Omega Centauri from the northern hemisphere, as both have nearly the same right ascension to within 10 arc minutes of each other. Both currently transit the southern meridian at around 11:00 AM local in late May, and Omega Centauri lies just 35 degrees — about 3 ½ hand widths held at arm’s length — south of Spica.

And speaking of Centaurus, the constellation was also recently host to a naked eye nova last year as well. Nova Cen 2013 topped out at magnitude +3.3, though it was placed much farther south than Omega Centauri.

Another unique target in the constellation Centaurus is known as Przybylski’s Star. A seemingly nondescript +8th magnitude star, Przybylski’s Star has some peculiar spectral properties of rare trace elements. It also sits near the same declination as Omega Centauri at -46 43’ and has a right ascension of 11 hours 38’.

Finally, there’s another southern hemisphere treat peeking just above the southern horizon on late May and June evenings… look about 13 degrees to the lower right of Omega Centauri at around 10:30 PM local in late May, and you might just spy Gacrux (Gamma Crucis), the +1.6 magnitude star that makes up the “head” of the constellation Crux, the Southern Cross. This tough to spot target just tops out at 5 degrees above the southern horizon from here in Tampa Bay, Florida, beckoning northern hemisphere observers on these sultry May and June evenings to the jewels that lie just beyond the horizon to the south.