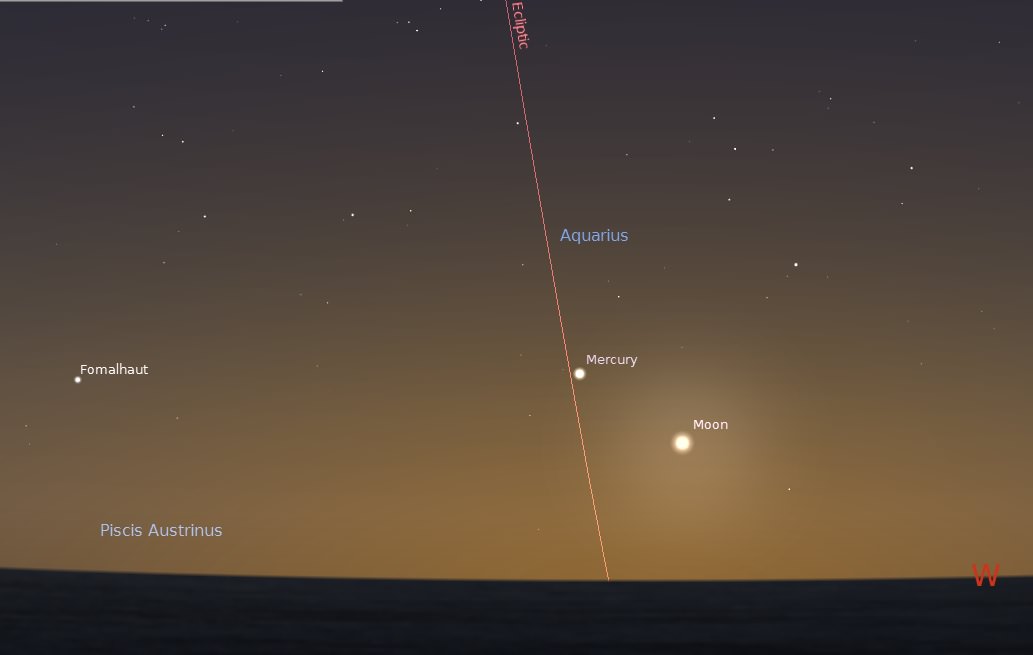

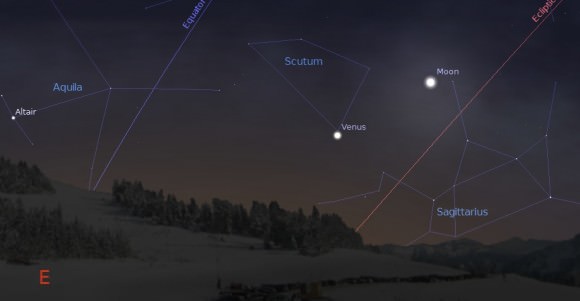

Are you a chronic early riser? Observational astronomy often means late nights and early mornings as daylight lengths get longer for northern hemisphere residents in February through March. But this year offers another delight for the early morning crowd, as the Venus is hanging out in the dawn skies for most of 2014.

You may have already caught sight of the brilliant world: it’s hard to miss, currently shinning at a dazzling -4.5 magnitude in the dawn. Venus is the brightest planet as seen from Earth and the third brightest natural object in the night sky after the Sun and the Moon.

Venus just passed between the Earth and the Sun last month on January 11th at inferior conjunction. Passing over five degrees north of the Sun, this was a far cry from the historic 2012 transit of the solar disk, a feat that won’t be replicated again until 2117 AD.

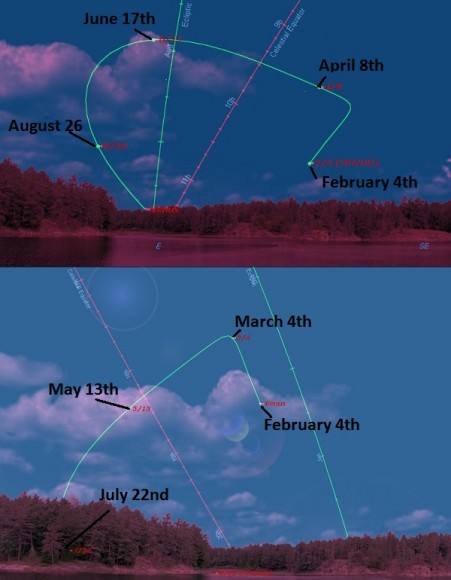

But February and March offer some notable events worth watching out for as Venus wanders in the dawn.

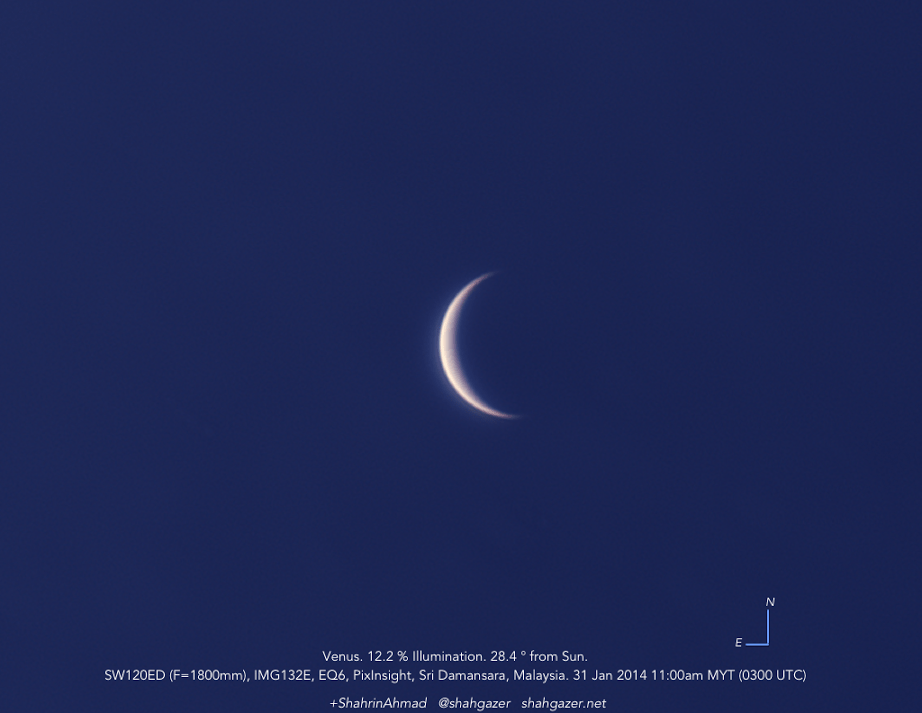

This week sees Venus thicken as a 48” 16% illuminated waxing crescent as it continues to present more of its daytime side to the Earth. We’ve always thought that it was a bit of cosmic irony that the closest planet too us presents no surface detail to observers: Venus is a cosmic tease. This assured that astronomers knew almost nothing about Venus until the dawn of the Space Age — guesses at its rotational speed and surface conditions were all widely speculative. Ideas of a vast extraterrestrial jungle or surface-spanning seas of seltzer water oceans gave way to the reality of a shrouded hellish inferno with noontime temps approaching 460 degrees Celsius. Venus is also bizarre in the fact that it rotates once every 243 Earth days, which is longer than its 224.7 day year — you could easily out walk a Venusian sunrise, that is if you could somehow survive to see it from its perpetually clouded surface!

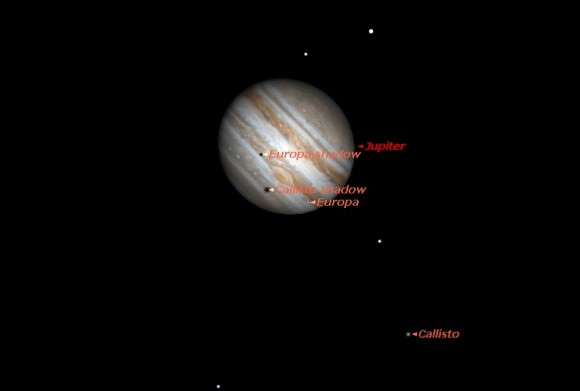

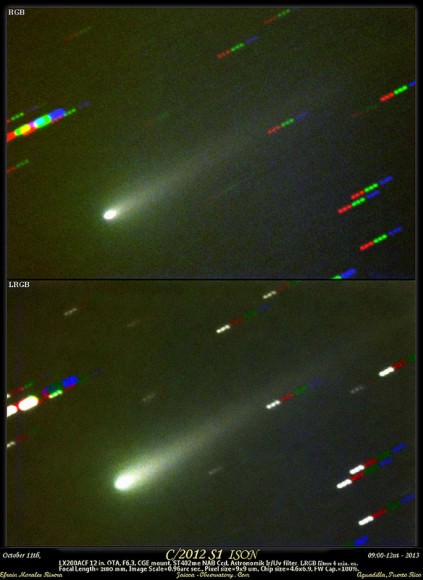

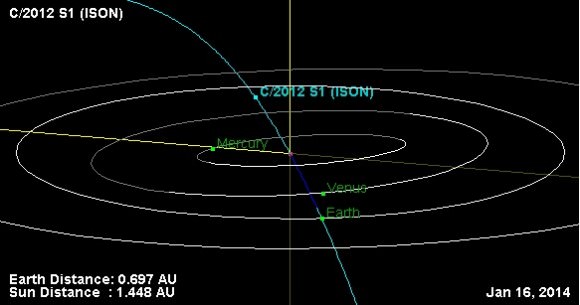

Venus also passes 4.3 degrees from faint Pluto this week on February 5th. And while Pluto is a tough catch at over a million times fainter than Venus, it’s interesting to consider that NASA’s New Horizons and ESA’s Rosetta spacecraft are also currently off in the same general direction:

Venus also reaches greatest brilliancy at magnitude -4.6 next week on February 11th. Venus is bright enough to cast a shadow onto a high contrast background, such as freshly fallen snow. Can you see your “Venusian shadow” with the naked eye? How about photographically?

Venus then goes on to show its greatest illuminated extent to us on February 15th. This combination occurs because although the crescent of Venus is fattening, the apparent size of the disk is shrinking as the planet pulls away from us in its speedy interior orbit. Can you spy the elusive “ashen light of Venus” through a telescope? Long a controversy, this has been reported by observers as a dim “glow” on the nighttime hemisphere of Venus. Proposed explanations for the ashen light of Venus over the years have been airglow, aurorae, lightning, Venusian land clearing activity (!) or, more likely, an optical illusion.

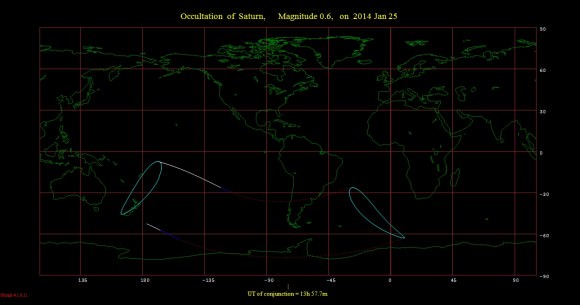

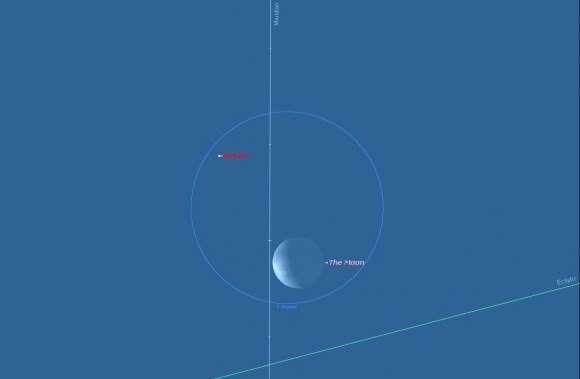

And speaking of which, the crescent Venus gets occulted by the waning crescent Moon on February 26th. Observers in western Africa will see this occur in the predawn skies, and the rest of us will see a close pass of the pair worldwide. Can you spot Venus near the crescent Moon in the daytime sky on the 26th?

In March, Venus begins the slide southward towards the point occupied by the Sun months earlier and heads towards its greatest westward elongation for 2014 on March 22nd at 46.6 degrees west of the Sun. Interestingly, Venus is tracing out roughly the same track it took 8 years ago in 2006 and will trace again in 2022, when it will also spend a majority of the year in the dawn once again. The 8-year repeating cycle of Venus is a result of the planet completing very nearly 13 orbits of the Sun to our 8. Ancient cultures, including the Maya, Egyptians, and Babylonian astronomers all knew of this period.

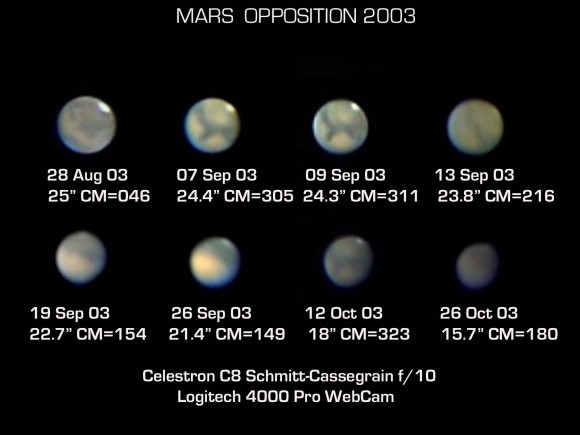

Through the telescope, Venus appears at a tiny “half-moon” phase 50% illuminated at greatest elongation, a point known as dichotomy. It’s interesting to note that theoretical and observed dichotomy can actually vary by several days surrounding greatest elongation. An optical phenomenon, or a true observational occurrence? When do you judge that dichotomy occurs in 2014?

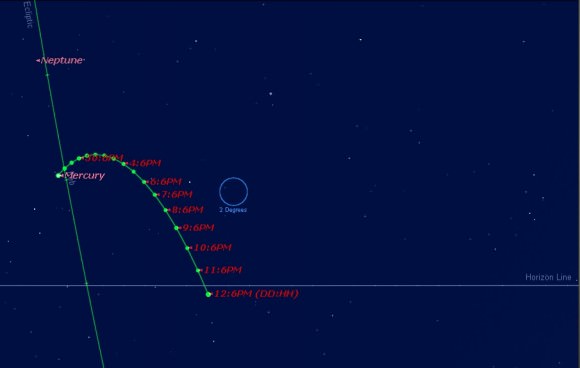

In April, one of the closest planetary conjunctions occurs of 2014 on the 12th involving Neptune and Venus at just 40’ apart, a little over the span of a Full Moon. Can you squeeze both into an eyepiece field of view? At +7.7th magnitude, Neptune shines at over 25,000 times fainter than Venus. Neith, the spurious “moon” of Venus described by 18th century astronomers lives!

But two even more dramatic conjunctions occur late in the summer, when Jupiter passes just 15’ from Venus on August 18th and Regulus stands just 42’ from Venus on September 5th. Fun fact: Venus actually occulted Regulus last century on July 7th, 1959!

From there on out, Venus heads toward superior conjunction on the far side of the Sun on October 25th, to once again emerge into the dusk sky through late 2014 and 2015.

Be sure to check out these dawn exploits of Venus through this Spring season and beyond!