It’s hard to believe that it’s been with us for a decade now.

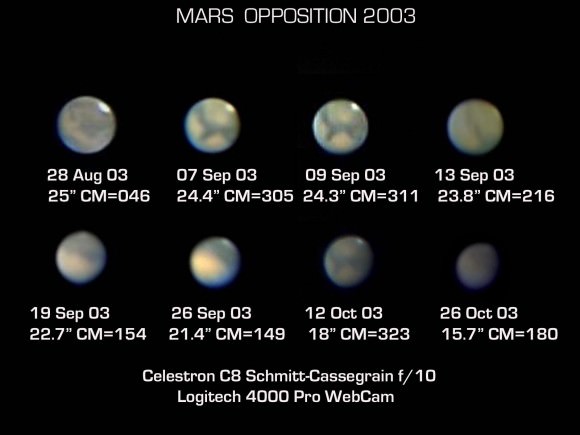

Ten years ago this week, the planet Mars reached made an exceptionally close pass of the planet Earth. This occurred on August 27th, 2003, when Mars was only 56 million kilometres from our fair planet and shined at magnitude -2.9.

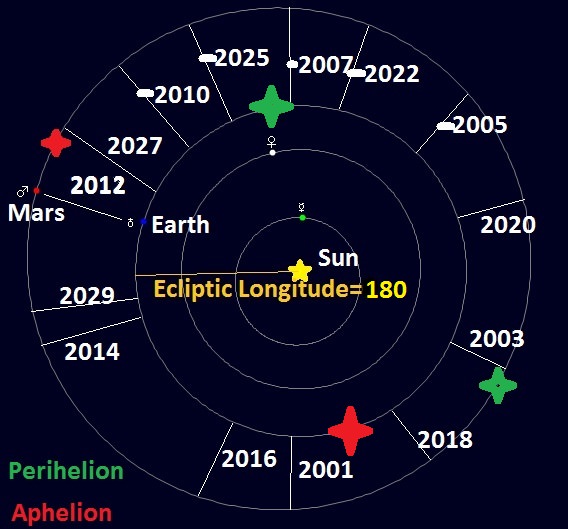

Such an event is known as opposition. This occurs when a planet with an orbit exterior to our own reaches a point opposite to the Sun in the sky, and rises as the Sun sets. In the case of Mars, this occurs about every 2.13 years.

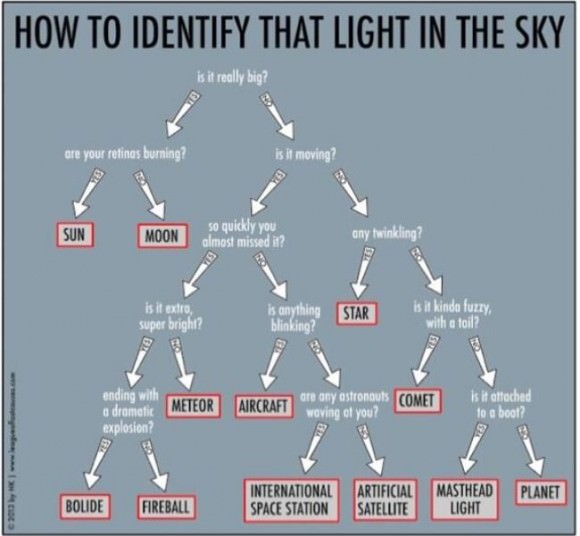

But another myth arose in 2003, one that now makes its return every August, whether Mars does or not.You’ve no doubt gotten the chain mail from a well-meaning friend/relative/coworker back in the bygone days a decade ago, back before the advent social media when spam was still sorta hip. “Mars to appear as large as the Full Moon!!!” it breathlessly exclaimed. “A once in a lifetime event!!!”

Though a little over the top, the original version did at least explain (towards the end) that Mars would indeed look glorious on the night of August 27th, 2003 … through a telescope.

But never let facts get in the way of a good internet rumor. Though Mars didn’t reach opposition again until November 7th 2005, the “Mars Hoax” email soon began to make its rounds every August.

Co-workers and friends continued to hit send. Spam folder filled up. Science news bloggers debunked, and later recycled posts on the silliness of it all.

Now, a decade later, the Mars Hoax seems to have successfully made the transition over to social media and found new life on Facebook.

No one knows where the Mars Hoax meme goes to weather the lean months, only to return complete with all caps and even more exclamation points each and every August. Is it the just a product of the never ending quest for the almighty SEO? Are we now destined to recycle and relive astronomical events in cyber-land annually, even if they’re imaginary?

Perhaps, if anything there’s a social psychology study somewhere in there, begging the question of why such a meme as the Mars Hoax endures… Will it attain a mythos akin to the many variations of a “Blue Moon,” decades from now, with historians debating where the cultural thread came from?

Here are the facts:

-Mars reaches opposition about every 2.13 Earth years.

-Due to its eccentric orbit, Mars can vary from about 56 million to over 101 million kilometres from the Earth during oppositions.

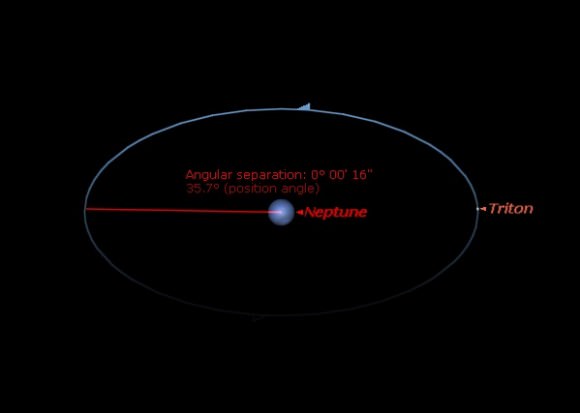

-Therefore, Mars can appear visually from 13.8” to 25.1” arc seconds in size.

-But that’s still tiny, as the Moon appears about 30’ across as seen from the Earth. You could ring the local horizon with about 720 Full Moons end-to-end, and place 71 “maxed out Mars’s” with room to spare across each one of them!

-And although the Full Moon looks huge, you can cover it up with a dime held at arm’s length…. Try it sometime, and amaze your email sending/Facebook sharing friends!

–Important: Mars NEVER gets large enough to look like anything other than a star-like point to the naked eye.

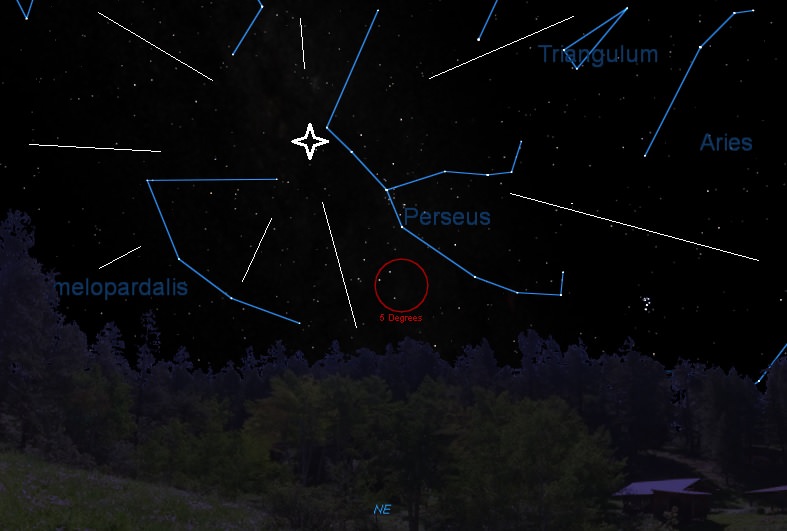

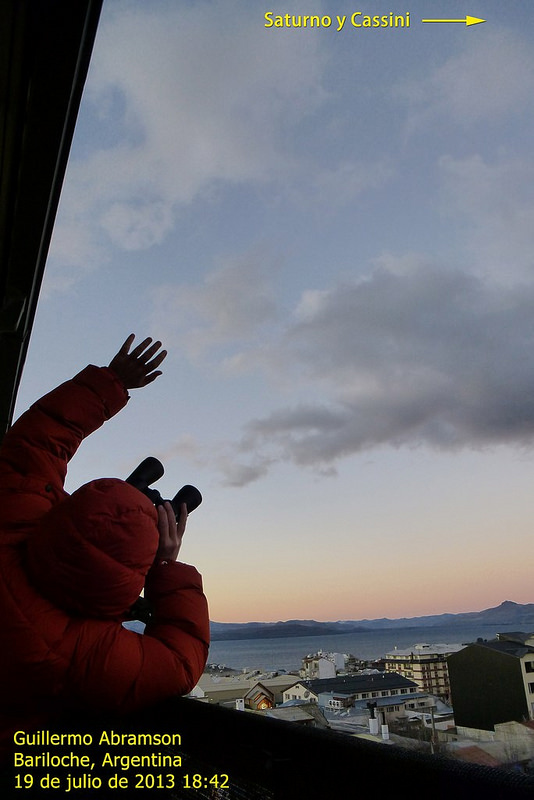

-And finally, and this is the point that should be getting placed in all caps on Facebook, to the tune of thousands of likes… MARS ISN’T EVEN ANYWHERE NEAR OPPOSITION in August 2013!!! Mars is currently low in the dawn sky in the constellation Cancer on the other side of the Sun. Mars won’t be reaching opposition until April 8th, 2014, when it will reach magnitude -1.4 and an apparent size of 15.2” across.

Still, like zombies from the grave, this myth just won’t die. In the public’s eye, Mars now shines “As big as” (or bigger, depending on the bad hyperbole used) as Full Moon now every August. Friends and relatives hit send, (or these days, “share” or “retweet”) observatories and planetariums get queries, astronomers shake their heads, and science bloggers dust off their debunking posts for another round. Hey, at least it’s not 2012, and we don’t have to keep remembering how many “baktuns are in a piktun…”

What’s a well meaning purveyor & promoter science to do?

Feed those hungry brains a dose of reality.

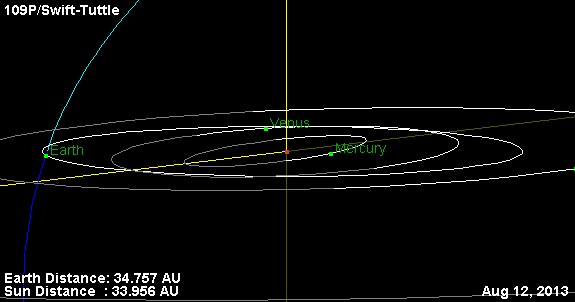

There are real things, fascinating things about Mars afoot. We’re exploring the Red Planet via Mars Curiosity, an SUV-sized, nuclear powered rover equipped with a laser. The opposition coming up next year means that the once every 2+ year launch window to journey to Mars is soon opening. This time around, the Mars Atmosphere and Volatile EvolutioN (MAVEN) mission and, just perhaps, India’s pioneering Mars Orbiter Mission may make the trip. Launching from Cape Canaveral on November 18th, MAVEN seeks to answer the questions of what the climate and characteristics of Mars were like in the past by probing its tenuous modern day atmosphere.

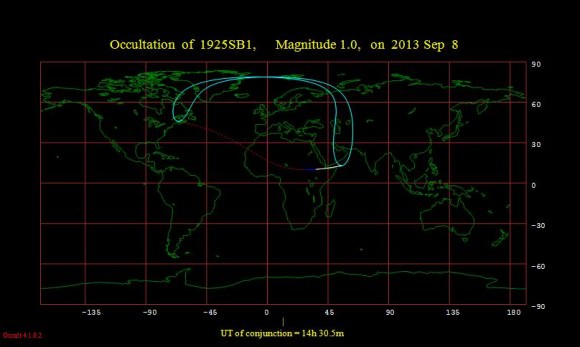

And as opposition approaches in 2014, Mars will again present a fine target for small telescopes. As a matter of fact, Mars will pass two intriguing celestial objects next month, passing in front of the Beehive cluster and — perhaps — a brightening Comet ISON. More to come on that later this week!

And it’s worth noting that after a series of bad oppositions in 2010 and 2012, oppositions in 2014 and 2016 are trending towards more favorable. In fact, the Mars opposition of July 27th, 2018 will be nearly as good as the 2003 approach, with Mars appearing 24.1” across. Not nearly as “large as a Full Moon” by a long shot, but hey, a great star party target.

Will the Mars Hoax email enjoy a resurgence on Facebook, Twitter or whatever is in vogue then? Stay tuned!