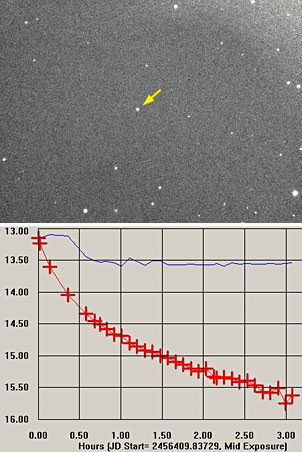

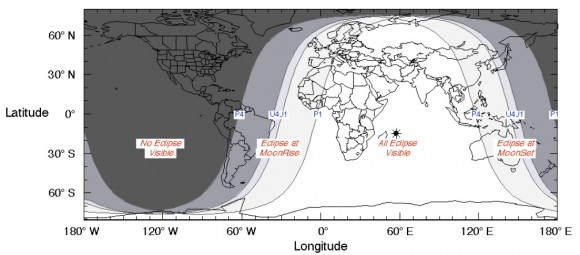

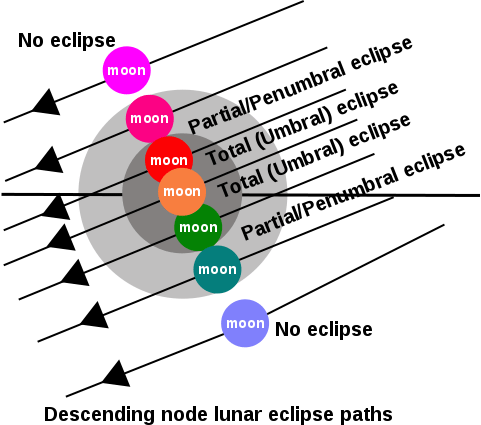

As the first eclipse season of 2013 comes to an end this weekend, an extremely subtle lunar eclipse occurs on the night of Friday, May 24th going into the morning of Saturday, May 25th. And we do mean subtle, as in invisible to the naked eye… this eclipse only lasts 34 minutes in duration and less than 2% of the disk of the Moon enters the bright outer penumbra of the Earth’s shadow!

So, why talk about such a non-event at all?

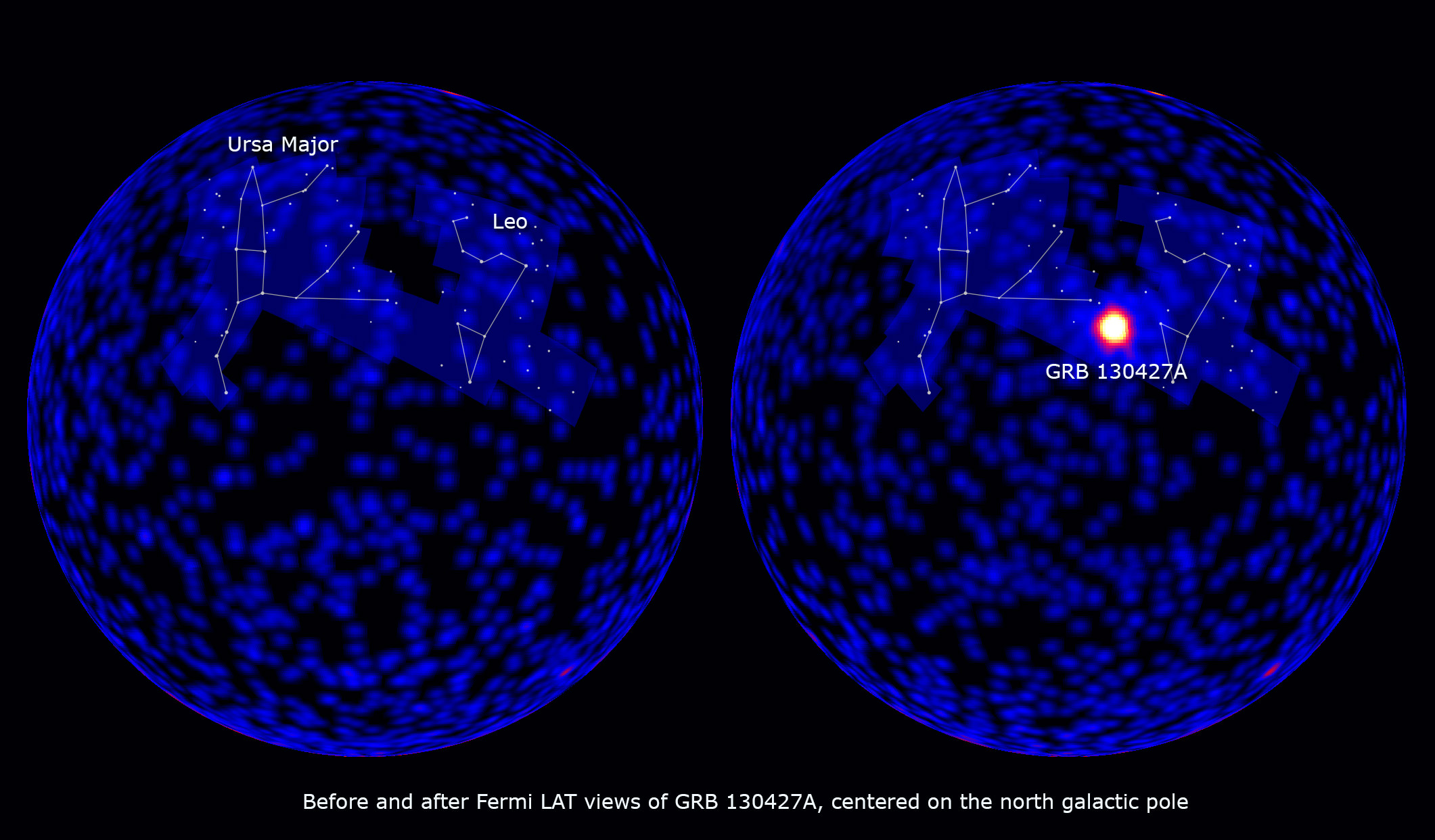

Great things come from such humble beginnings. And while this weekend’s eclipse is one mostly for the almanacs and astronomical tables rather than a true observational event, it also marks the start of a new lunar saros cycle.

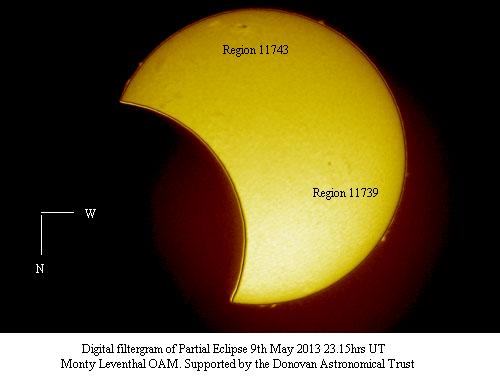

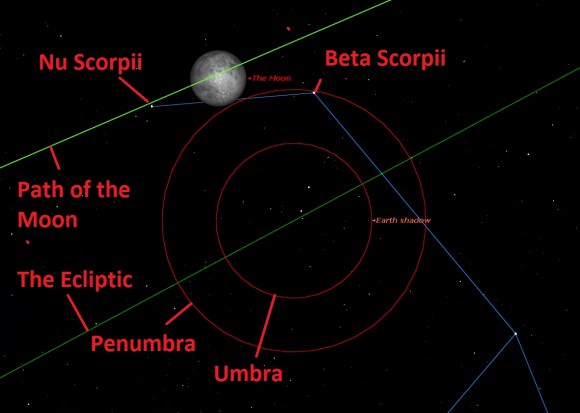

This weekend’s eclipse is one of five for 2013, a year which contains two solars and three lunars. This eclipse marks the end of the first “eclipse season” of the year, a time when the intersection of the Moon’s orbit (known as nodes) and the ecliptic nearly coincide with the position of the Sun (for a solar eclipse at New Moon) and the Earth’s shadow (for a lunar eclipse at Full Moon).

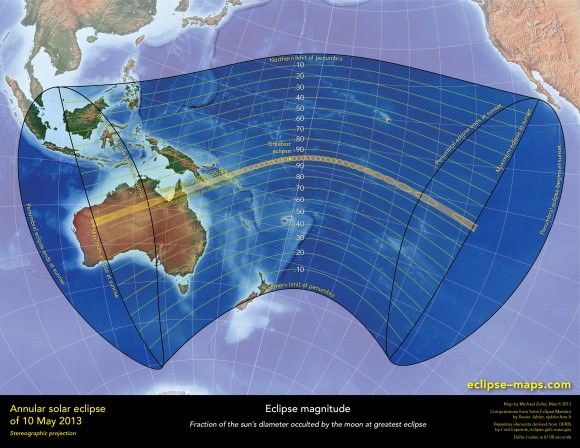

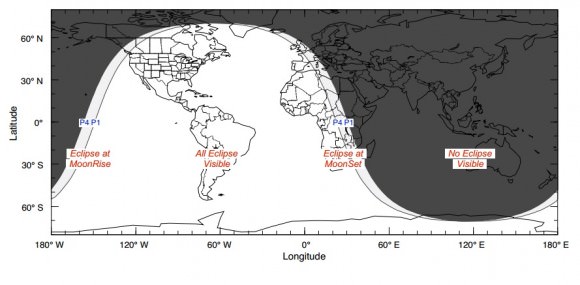

The current season began with a very slight partial eclipse on April 25th, followed by an annular eclipse on May 10th. It will last only 33 minutes and 45 seconds in duration starting at 03:53:11 UTC on May 25th. The Moon will be high over the Americas at the time, but again, shading on the southern limb of the Moon will be too slight to be seen.

Curiously, SLOOH will be providing live coverage of the eclipse, although again, it will be too slight to see.

What is a saros? A saros is a period of 18 years 11 days and 8 hours after which an eclipse cycle lines up, producing a similar eclipse to the one that preceded it 18 years before. Note that due to its 8 hour offset, the Earth will have rotated 120° and the visibility region will have shifted westward.

In said period, three lunar cycles very nearly line up;

The Anomalistic month (the period the Moon takes to go from one perigee to another) = 27.555 days.

The Draconic month (the period the Moon takes to return to the same node) = 27.212 days.

The Synodic month (the most familiar one, the period between similar phases) = 29.531 days.

Note that:

239 Anomalistic months = 239×27.555= 6585.645 days.

242 Draconic months = 242×27.212=6585.304 days.

223 Synodic months = 223×29.531=6585.413 days.

There’s that mis-alignment of a third of a day again (8 hours) for every 18 years and 11 days. This also causes the node of each eclipse in the cycle to drift eastward by 0.5° along the ecliptic. Thus, each eclipse isn’t exactly the same. A lunar saros series starts with a very brief penumbral like this weekend’s, becomes deeper and deeper every 18+ year period until partial and total eclipses begin centuries down the road. Thereafter, the cycle reverses, until a final faint penumbral marks the end of the lunar saros.

After this weekend’s eclipse, the next start of a lunar saros won’t occur until November 8th 2060 with the start of saros 156. The last new saros series (number 149) began on June 13th, 1984.

There are numbered saros series for both lunar and solar eclipses. There are currently 41 saroses (the plural of saros) active with the inclusion of this weekend’s start of lunar saros 150.

Saros 150, of which this eclipse is the 1st of 71, will last for just over 1,262 years. It will begin to produce partial eclipses on August 20th, 2157 and produce its 1st total on its 32nd lunar eclipse on April 29th, 2572.

It amazes me that ancient cultures such as the Chaldeans new of saros cycles and could predict eclipses. Being geographically isolated, lunar eclipse cycles would have been easier to decipher than solar ones, as you only have to be on the Moonward facing hemisphere of the Earth to witness the eclipse. They may well have stumbled upon the saros while attempting to calculate a slightly longer 19 year period known as a Metonic cycle to align ancient luni-solar calendars.

And yes, that 8 hour offset also means that after a triple saros period, lunar and solar eclipses of the same saros series do return to roughly the same longitude every 54 years & 34 days. This is known as an exeligmos, and if you get this on a triple-word score in Scrabble, you can safely retire from the game.

And while this eclipse is more of academic than observational interest, you can always enjoy the light of a brilliant Full Moon. The May Full Moon is referred to as the Flower, Milk, and Corn Planting Moon by the Algonquian Indians of North America, alluding the latent season of Spring.

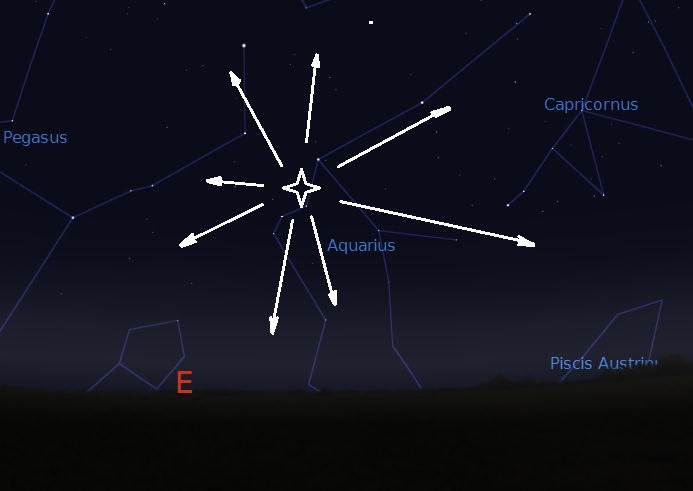

Also, keep an eye out for several conjunctions and occultations this week by the Moon with bright stars and planets.

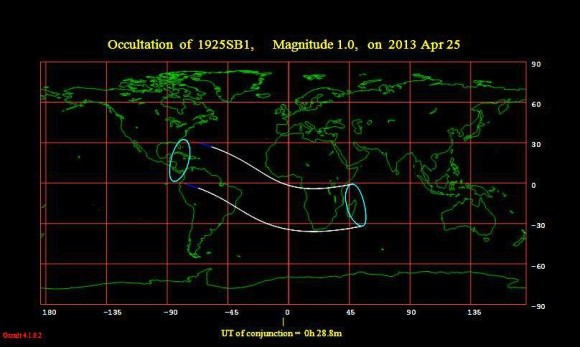

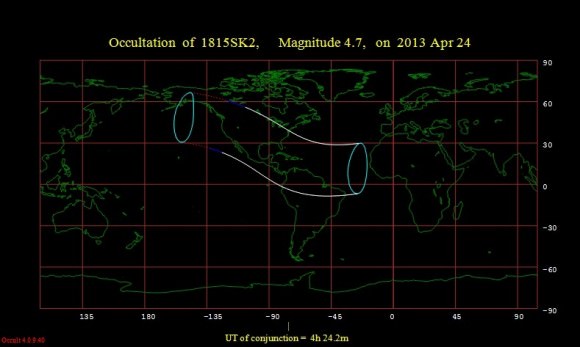

The first up is the bright star Spica (Alpha Virginis) which gets occulted by the waxing gibbous Moon around ~11:00 UT on Wednesday, May 22nd for viewers across northern Australia, southern Asia and the South Pacific. Spica is one of four stars brighter than magnitude +1.5 that the Moon can occult, the others being Antares, Aldebaran and Regulus. This is the 6th occultation in a cycle of 13 of Spica by the Moon spanning 2013.

The planet Saturn will lie about 4° north of the waxing gibbous Moon on the following evening of May 23rd.

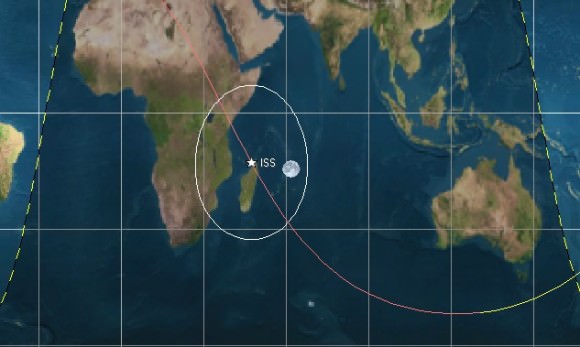

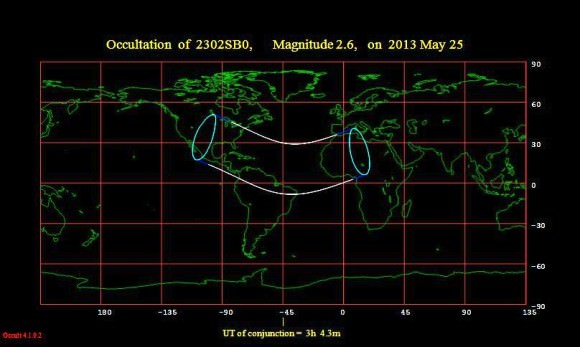

Also, watch for an occultation of the +2.6th magnitude star Beta Scorpii on the evening of May 24th around the time of the lunar eclipse. This will be a difficult one, as the Moon will be near 100% illumination. Conjunction of the Moon and Beta Scorpii in right ascension occurs at 3:04 UT on May 25th, about 2.5 hours after Full. The occultation will span the southeastern US, Caribbean, northern South America and western Africa.

2013 isn’t a grand year for eclipses. We’ve got two more in the late season of the year, another slightly deeper penumbral on October 18th and a hybrid solar eclipse on November 3rd. And when, may you ask, will we FINALLY have another total lunar eclipse? Stick around ‘til U.S. Tax Day next year (April 15th 2014) for a total lunar eclipse spanning the Americas!