Greetings, fellow SkyWatchers! It’s going to be a great week to study the Moon – and bright Jupiter is just begging for some quality eyepiece time. Need more? Then why don’t we study some very interesting variable stars, too? It’s all out there… Just waiting on you!

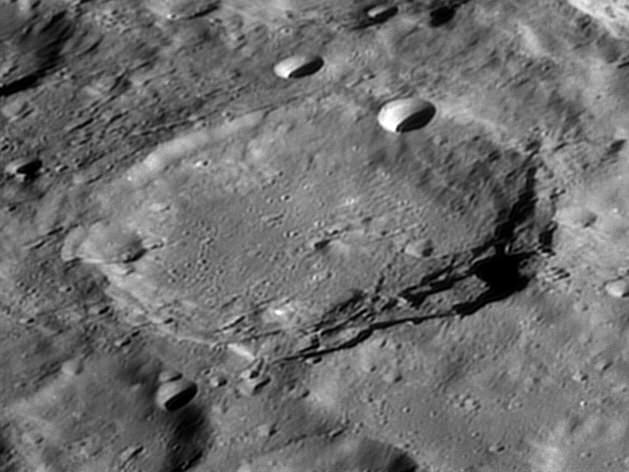

Monday, November 19 – Now we’re ready for some serious lunar study. Our first order of business will be to identify crater Curtius. Directly in the center of the Moon is a dark-floored area known as the Sinus Medii. South of it will be two conspicuously large craters – Hipparchus to the north and ancient Albategnius to the south. Trace along the terminator toward the south until you have almost reached its point (cusp) and you will see a black oval. This normal looking crater with the brilliant west wall is equally ancient crater Curtius. Because of its high southern latitude, we shall never see the entire interior of this crater – and neither has the Sun! It is believed the inner walls are quite steep, and so crater Curtius’ full interior has never been illuminated since its formation billions of years ago. Because it has remained dark, we can speculate there may be “lunar ice” (water ice possibly mixed with regolith) pocketed inside its many cracks and rilles which date back to the Moon’s formation!

Because our Moon has no atmosphere, the entire surface is exposed to the vacuum of space. When sunlit, the surface reaches up to 385 K, so any exposed lunar ice would vaporize and be lost because the Moon’s gravity could not hold it. The only way for ice to exist would be in a permanently shadowed area. Near Curtius is the Moon’s south pole, and imaging from the Clementine spacecraft showed around 15,000 square kilometers of area where such conditions could exist. So where did this ice come from? The lunar surface never ceases to be pelted by meteorites – most of which contain water-related ice. As we know, many craters were formed by just such impacts. Once hidden from the sunlight, this ice could continue to exist for millions of years.

Now turn your eyes or binoculars just west of bright Aldebaran and have a look at the Hyades Star Cluster. While Aldebaran appears to be part of this large, V-shaped group, it is not an actual member. The Hyades cluster is one of the nearest galactic clusters, and it is roughly 130 light-years away in the center. This moving group of stars is drifting slowly away towards Orion, and in another 50 million years it will require a telescope to view!

Tuesday, November 20 – Today celebrates another significant astronomer’s birth – Edwin Hubble. Born 1889, Hubble became the first American astronomer to identify Cepheid variables in M31 – which in turn established the extragalactic nature of the spiral nebulae. Continuing with the work of Carl Wirtz, and using Vesto Slipher’s redshifts, Hubble then could calculate the velocity-distance relation for galaxies. This has become known as “Hubble’s Law” and demonstrates the expansion of our Universe.

Tonight we’re going to ignore the Moon and head just a little more than a fistwidth west of the westernmost bright star in Cassiopeia to have a look at Delta Cephei (RA 22 29 10.27 Dec +58 24 54.7). This is the most famous of all variable stars and the granddaddy of all Cepheids. Discovered in 1784 by John Goodricke, its changes in magnitude are not due to a revolving companion – but rather the pulsations of the star itself.

Ranging over almost a full magnitude in 5 days, 8 hours and 48 minutes precisely, Delta’s changes can easily be followed by comparing it to nearby Zeta and Epsilon. When it is its dimmest, it will brighten rapidly in a period of about 36 hours – yet take 4 days to slowly dim again. Take time out of your busy night to watch Delta change and change again. It’s only 1000 light-years away, and doesn’t even require a telescope! (But even binoculars will show its optical companion.)

Wednesday, November 21 – Before we go star hopping this evening, let’s go south on the lunar globe in hopes of catching a very unusual event. On the southern edge of Mare Nubium is the old walled plain Pitatus. Power up. On the western edge you will see smaller and equally old Hesiodus. Almost central along their shared wall there is a break to watch for when the terminator is close. For a brief moment, sunrise on the Moon will pass through this break creating a beam of light across the crater floor in a beautiful phenomenon known as the “Hesiodus Sunrise Ray.” For a very brief moment, a shaft of sunlight will shine through this break and create an experience you will never forget. If the terminator has moved beyond it at your observing time, then look to the south for small Hesiodus A. This is an example of an extremely rare double concentric crater. This formation is caused by one impact followed by another, slightly smaller impact, at exactly the same location.

Now, let’s continue our stellar studies with the central-most star in the lazy “W” of Cassiopeia – Gamma…

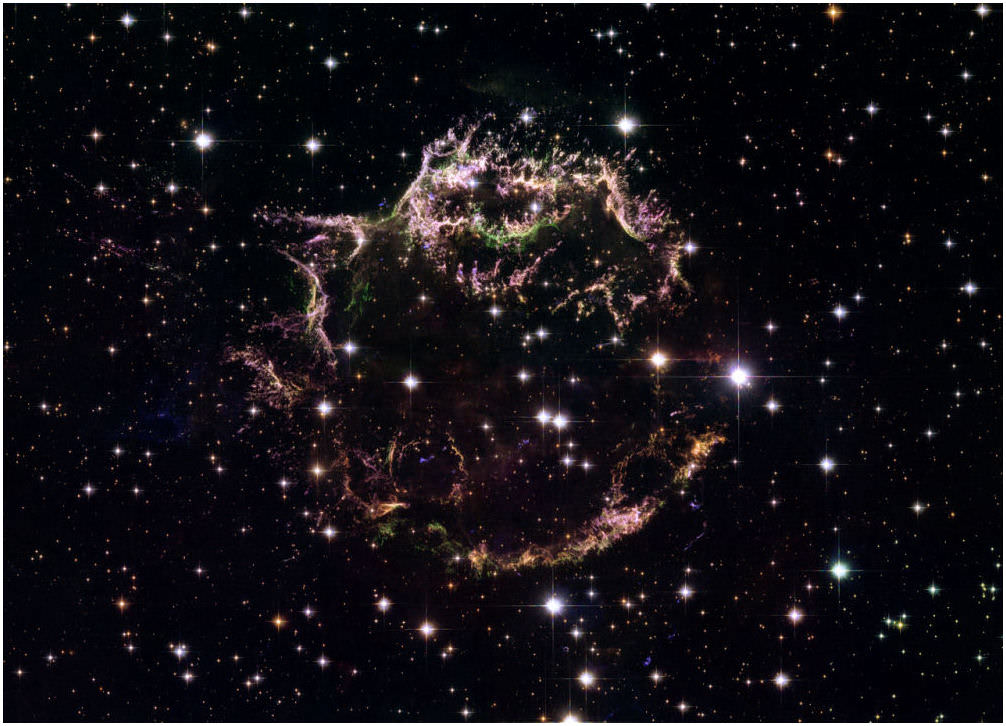

At the beginning of the 20th century, the light from Gamma appeared to be steady, but in the mid-1930s it took an unexpected rise in brightness. In less than 2 years it jumped by a magnitude! Then, just as unexpectedly, it dropped back down again in roughly the same amount of time. A performance it repeated some 40 years later!

Gamma Cassiopeiae isn’t quite a giant and is still fairly young on the evolutionary scale. Spectral studies show violent changes and variations in the star’s structure. After its first recorded episode, it ejected a shell of gas which expanded Gamma’s size by over 200% – yet it doesn’t appear to be a candidate for a nova event. The best estimate now is that Gamma is around 100 light-years away and approaching us at a very slow rate. If conditions are good, you might be able to telescopically pick up its disparate 11th magnitude visual companion, discovered by Burnham in 1888. It shares the same proper motion – but doesn’t orbit this unusual variable star. For those who like a challenge, visit Gamma again on a dark night! Its shell left two bright (and difficult!) nebulae, IC 59 and IC 63, to which we will return at the end of the month.

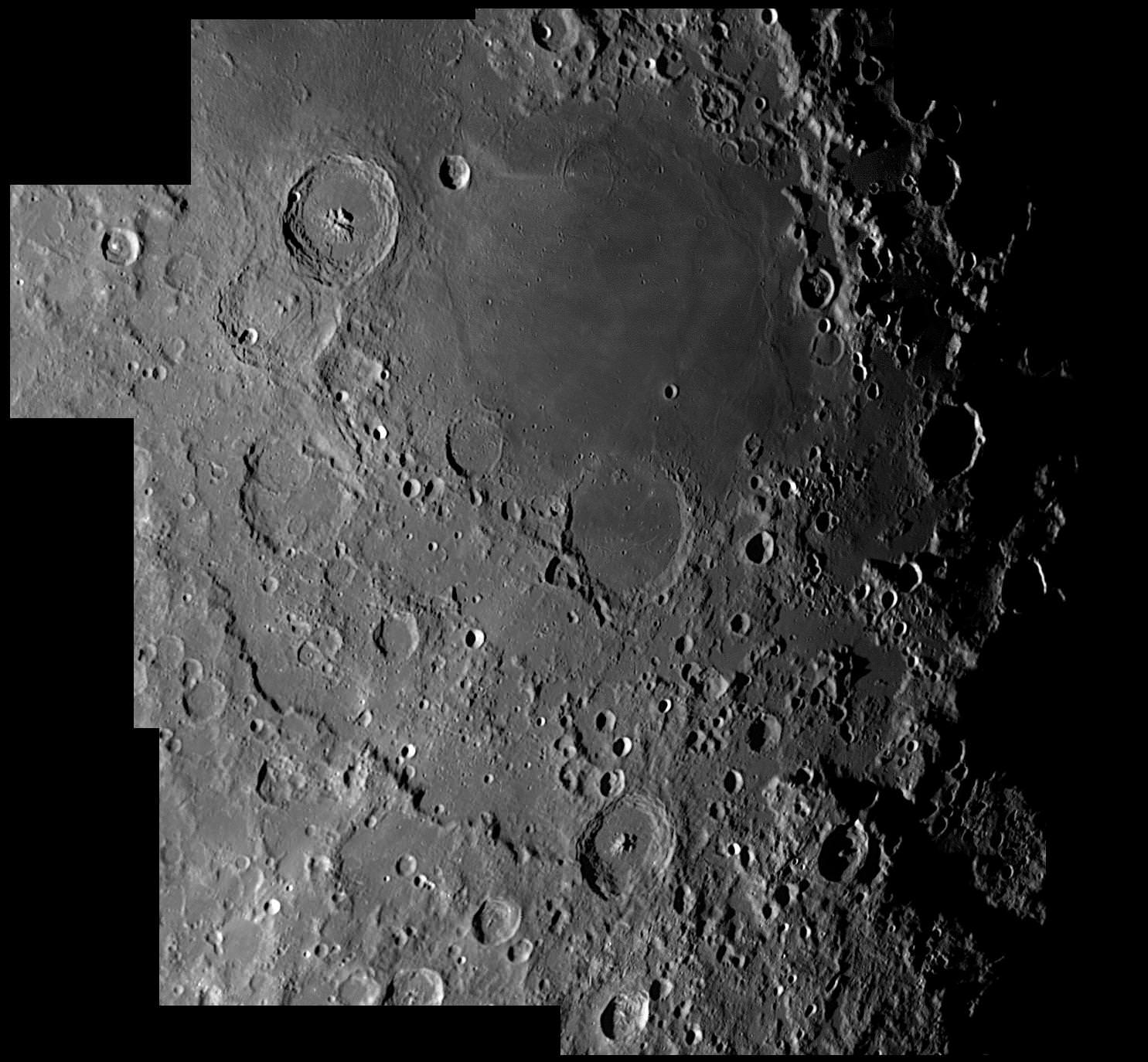

Thursday, November 22 – Tonight when you’re studying the Moon, return to our landmark Copernicus and travel south along the western shore of Mare Cognitum, the “Sea That Has Become Known” and look along the terminator for the Montes Riphaeus – “The Mountains In The Middle of Nowhere.” But are they really mountains? Let’s take a closer look. At the widest, this unusual range spans about 38 kilometers and runs for a distance of around 177 kilometers. Less impressive than most lunar mountain ranges, some peaks reach up to 1250 meters high, making these summits about the same height as our volcano Mt. Kilauea. While we are considering volcanic activity, consider that these peaks are all that is left of Mare Cognitum’s walls after lava filled it in. At one time this may have been amongst the tallest of lunar features!

Once you’ve studied the Montes Riphaeus, you’ll begin noticing another lunar crater that looks a whole lot like a smaller version of Copernicus – the highly under-rated crater Bullialdus. Located close to the center of Mare Nubium, even binoculars can make out Bullialdus when near the terminator. If you’re scoping – power up – this one is fun! Very similar to Copernicus, Bullialdus’ has thick, terraced walls and a central peak. If you examine the area around it carefully, you can note it is a much newer crater than shallow Lubiniezsky to the north and almost non-existent Kies (a real challenge) to the south. On Bullialdus’ southern flank, it’s easy to make out its A and B craterlets, as well as the interesting little Koenig to the southwest.

Friday, November 23 – Tonight in 1885, the very first photograph of a meteor shower was taken. Also, the weather satellite TIROS II was launched on this day in 1960. Carried to orbit by a three-stage Delta rocket, the “Television Infrared Observation Satellite” was about the size of a barrel, testing experimental television techniques and infrared equipment. Operating for 376 days, Tiros II sent back thousands of pictures of Earth’s cloud cover and was successful in its experiments to control the orientation of the satellite spin and its infrared sensors. Oddly enough, a similar mission – Meteosat 1 – also became the first satellite put into orbit by the European Space Agency, in 1977 on this day. Where is all this leading? Why not try observing satellites on your own! Thanks to wonderful on-line tools from NASA you can be alerted by e-mail whenever a bright satellite makes a pass for your specific area. It’s fun!

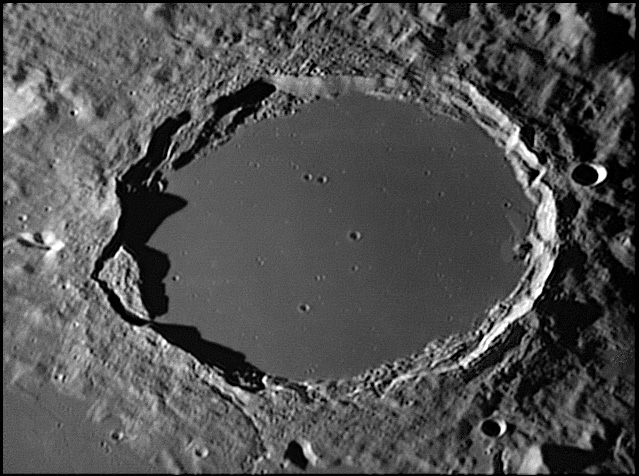

When you are ready to sail again, we’ll head to the Moon and cross the the western edge of the second largest lunar sea – Mare Imbrium – as we head northeast for the “lighthouse” points set on either side of the landmark “Bay of Rainbows”. They guard the opening to Sinus Iridum and they have names. The easternmost is Promentorium LaPlace, named for Pierre LaPlace. Little more than 56 kilometers in diameter, it rises above the gray sands some 3019 meters; almost identical in height to Buttermilk Mountain near Aspen. Promontorium Heraclides to the west covers roughly the same area, yet rises to little more than half of LaPlace’s height.

Saturday, November 24 – Tonight grab your telescope and head for the Moon and take another look at a feature you might have missed earlier in the year. ! Look west of very bright punctuation of crater Aristarchus for less prominent crater Herodotus. Just to the north you will see a fine white thread known as Schroter’s Valley. This inconspicuous feature winds its way across the Aristarchus plain for about 160 kilometers and measures about 3 to 8 kilometers wide, and about 1 kilometer deep. Schroter’s Valley is an example of a collapsed lava tube. It may have broken open when lava crossed the surface – or it may have settled downwards when a major meteor strike caused a shock wave. What we are looking at is a long, narrow cave on the surface which is very apparent when the lighting is correct.

Ready to aim for a bullseye? Then head for the bright, reddish star Aldebaran. Set your eyes, scopes or binoculars there and let’s look into the “eye” of the Bull.

Known to the Arabs as Al Dabaran, or “the Follower,” Alpha Tauri took its name for the fact that it appears to follow the Pleiades across the sky. In Latin it was Stella Dominatrix, yet the old English knew it as Oculus Tauri, or very literally the “eye of Taurus.” No matter which source of ancient astronomy lore we explore, there are references to Aldeberan.

As the 13th brightest star in the sky, it almost appears from Earth to be a member of the V-shaped Hyades star cluster, but its association is merely coincidental, since it is about twice as close to us as the cluster. In reality, Aldeberan is on the small end as far as K5 stars go, and like many other orange giants could possibly be a variable. Aldeberan is also known to have five close companions, but they are faint and very difficult to observe with backyard equipment. At a distance of approximately 68 light-years, Alpha is slightly less than 45 times larger than our own Sun and approximately 425 times brighter. Because of its position along the ecliptic, Aldeberan is one of the very few stars of first magnitude that can be occulted by the Moon.

Sunday, November 25 – As the Moon nears Full, it becomes more and more difficult to study, but there are still some features that we can take a look at. Before we go to our binoculars or telescopes, just stop and take a look. Do you see the “Cow Jumping over the Moon”? It is strictly a visual phenomenon—a combination of dark maria which looks like the back, forelegs and hindlegs of the shadow of that mythical animal.

While Cassiopeia is in prime position for most northern observers, let’s return tonight for some additional studies. Starting with Delta, let’s hop to the northeast corner of our “flattened W” and identify 520 light-year distant Epsilon. For larger telescopes only, it will be a challenge to find this 12″ diameter, magnitude 13.5 planetary nebula I.1747 in the same field as magnitude 3.3 Epsilon!

Using both Delta and Epsilon as our “guide stars” let’s draw an imaginary line between the pair extending from southwest to northeast and continue the same distance until you stop at visible Iota. Now go to the eyepiece…

As a quadruple system, Iota will require a telescope and a night of steady seeing to split its three visible components. Approximately 160 light-years away, this challenging system will show little or no color to smaller telescopes, but to large aperture, the primary may appear slightly yellow and the companion stars a faint blue. At high magnification, the 8.2 magnitude “C” star will easily break away from the 4.5 primary, 7.2″ to the east-southeast. But look closely at that primary: hugging in very close (2.3″) to the west-southwest and looking like a bump on its side is the B star!

Dropping back to the lowest of powers, place Iota to the southwest edge of the eyepiece. It’s time to study two incredibly interesting stars that should appear in the same field of view to the northeast. When both of these stars are at their maximum, they are easily the brightest of stars in the field. Their names are SU (southernmost) and RZ (northernmost) Cassiopeiae and both are unique! SU is a pulsing Cepheid variable located about 1000 light-years away and will show a distinctive red coloration. RZ is a rapidly eclipsing binary that can change from magnitude 6.4 to magnitude 7.8 in less than two hours. Wow!

Until next week? Clear skies!