An innovative solar observatory is adding a key piece to the puzzle of the enigma that is our Sun.

Its two of key questions in heliophysics: why does our Sun have a corona? And why is the temperature of the corona actually higher than the surface of the Sun?

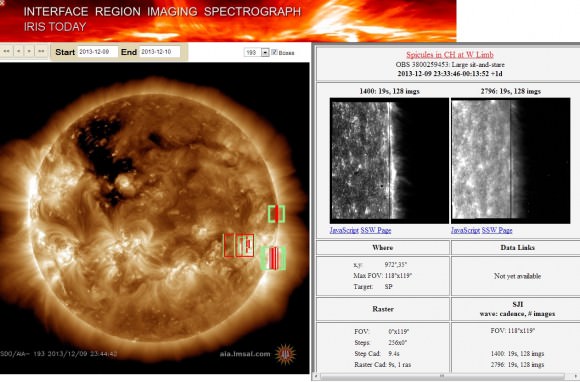

This week, researchers released results from the preliminary first six months of data from NASA’s Interface Region Imaging Spectrograph, known as IRIS. The findings were presented at the Fall American Geophysical Union Meeting this past Monday.

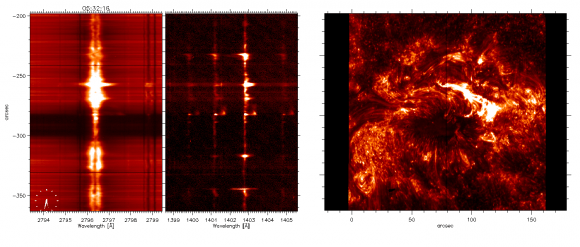

IRIS was launched on June 27th of this year on a Pegasus-XL rocket deployed from the belly of a Lockheed L-1011 aircraft flying out of Vandenberg Air Force Base. IRIS can focus in on a very specific interface region of the Sun sandwiched between the dazzling solar photosphere and the transition to the corona. To accomplish this, IRIS employs an ultraviolet slit spectrograph looking at ionized gas spectra.

“The quality of images and spectra we are receiving is amazing,” IRIS Principal Investigator Alan Title said in a recent press release from the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. While other missions may take over a decade to go from the drawing board to the launch pad, IRIS was developed and deployed into Low Earth Orbit in just 44 months.

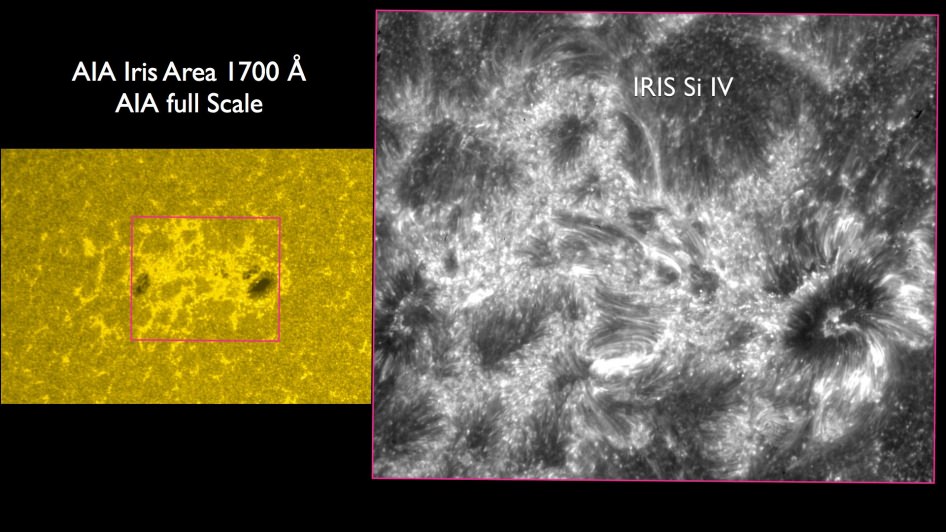

IRIS offers scientists a new tool to probe the Sun and a complimentary instrument to platforms such as Hinode, the Solar Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) and NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory. In fact, IRIS has a better resolution than SDO’s AIA imagers or Hinode when it comes to this key solar interface region. IRIS has a 20x greater resolution in time, and 25x the spatial resolution of any former space-based UV spectrometer deployed.

“We are seeing rich and unprecedented images of violent events in which gases are accelerated to very high velocities while being rapidly heated to hundreds of thousands of degrees,” said Lockheed Martin science lead on the IRIS mission Bart De Pontieu. These observations are key to backing up theoretical models of solar dynamics as well as testing and formulating new ones of how our Sun works.

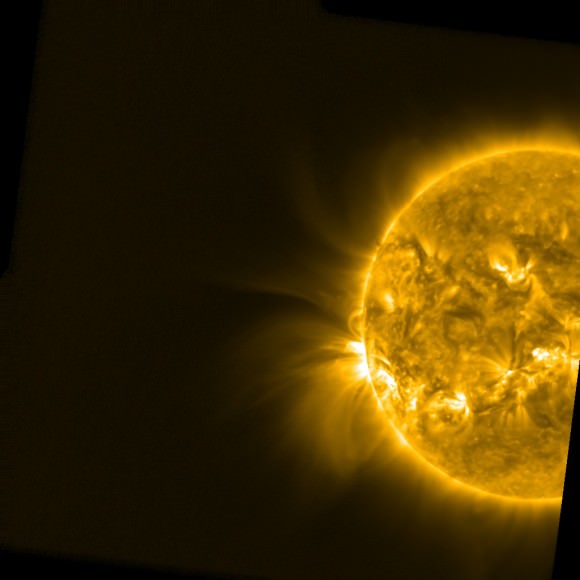

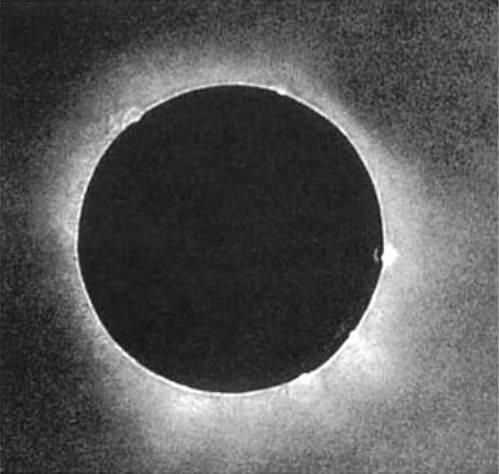

IRIS bridges this crucial gap between the photosphere and the lower chromosphere of the Sun. While the solar surface roils at relatively placid 6,000 degrees Celsius, temperatures rise into the range of 2-3 million degrees Celsius as you move up through the transition region and into the corona.

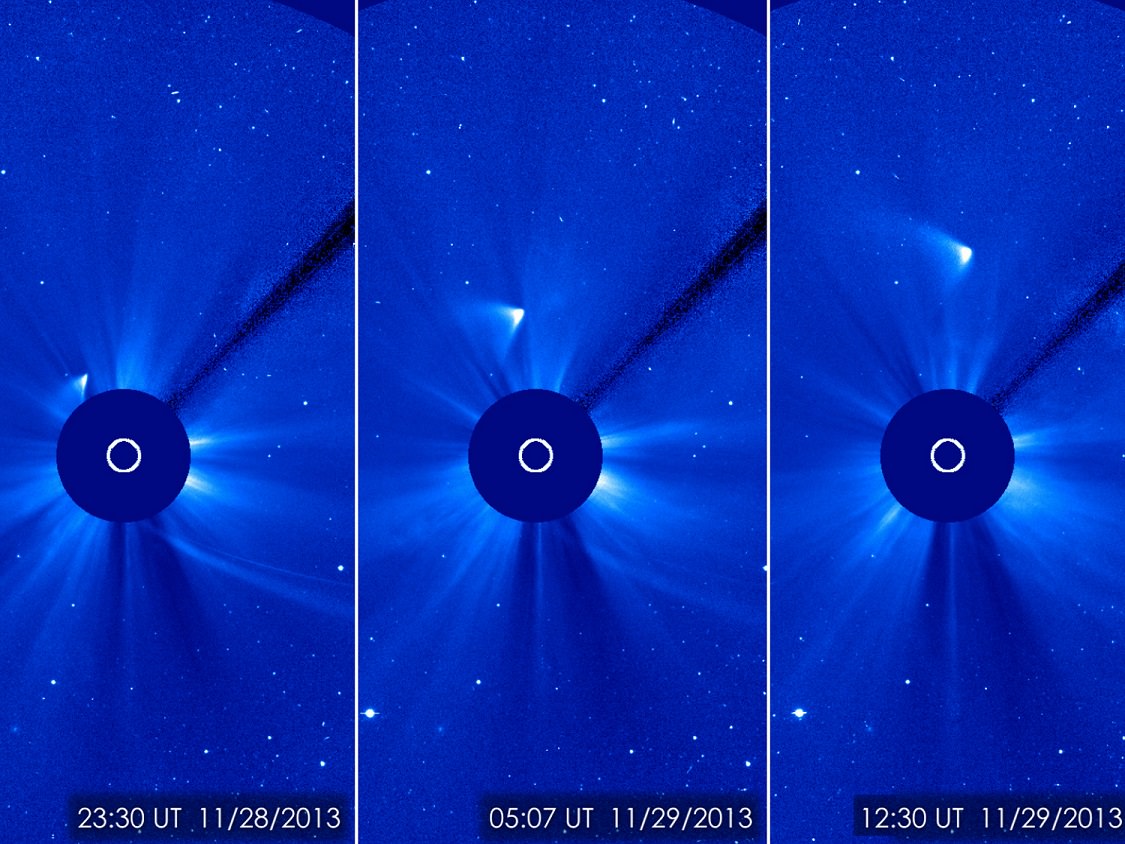

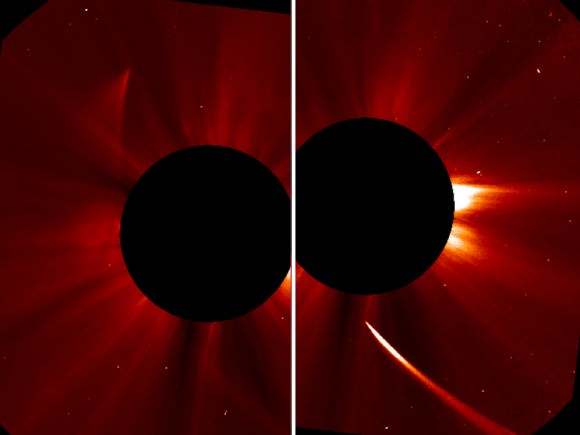

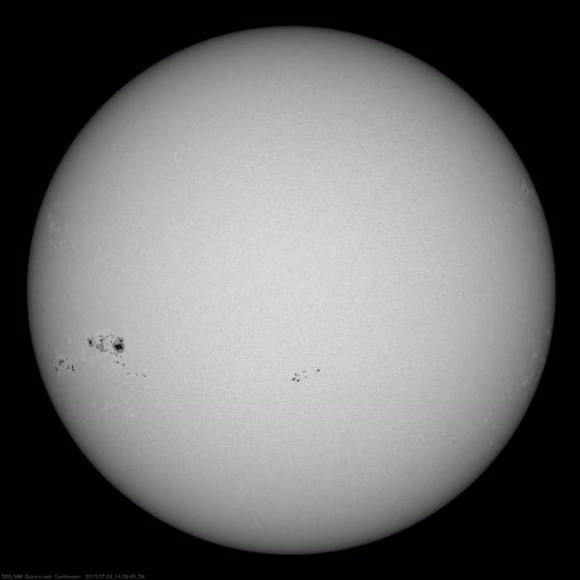

Two key solar phenomena that are of concern to solar researchers can be examined by IRIS in detail. One is the formation of prominences, which show up as long looping swirls of solar material rising up from the surface of the Sun. Prominences can be seen from backyard telescopes at hydrogen alpha wavelengths. IRIS can catch and track their early modeling with unprecedented resolution. Images released from IRIS show the fine structure of targeted prominences as they evolve and rise off the surface of the Sun. When a prominence and accompanying coronal mass ejection is launched in our direction, disruption of our local space environment caused by massive solar storm can result.

The second phenomenon targeted by IRIS is the formation of spicules, which are giant columns of gas rising from the photosphere. Although the spicules look like hair-fine structures through Earth-based solar telescopes, they can be several hundred kilometres wide and as long as the Earth. Short-lived, spicules race up from the surface of the Sun at up to 240,000 kilometres per hour and seem to play a key role in energy and heat transfer from the solar surface up through the atmosphere. IRIS is giving us a view of the evolution of spicules for the first time, and they’re proving to be even more complex than theory previously suggested.

“We see discrepancies between these observations and the models, and that is great news for advancing knowledge. By seeing something we don’t understand, we have a chance of learning something new,” Said University of Oslo astrophysicist Mats Carlsson.

Like SDO and SOHO, data and images from IRIS are free for the public to access online. Though the field of view for IRIS is a narrow 2’ to 4’ arc minutes on a side – the solar disk spans about 30’ as seen from the Earth – IRIS gives us a refined view of “where the action is.”

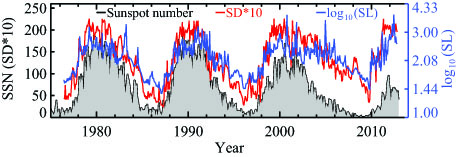

And this all comes at an interesting time, as our nearest star crosses the sputtering solar maximum for Cycle #24.

The equivalent of 50 million CPU hours were utilized in constructing and modeling what IRIS sees. The reconstruction was an international effort, spanning the Partnership for Advanced Computing in Europe, the Norwegian supercomputing collaboration, and NASA’s Ames Research Center.

IRIS also faced the additional challenge of weathering a 2.5 week period of inactivity due to the U.S. government shutdown this fall. Potential impacts due to sequestration remain an issue, though small explorer missions such as IRIS demonstrate how we can do more with less.

“We’ve made a giant step forward in characterizing the heat transfer properties of this region between the visible surface and the corona, which is key to understanding how the outer atmosphere of the Sun exists, and is key to understanding the outer atmosphere that the Earth lies in,” said Alan Title, referring to the tenuous heliosphere of the Sun extending out through the solar system.

Understanding the inner working of our Sun is vital: no other astronomical body has as big an impact on life here on Earth.

IRIS is slated for a two-year mission, though as is the case with most space-based platforms, researchers will work to get every bit of usefulness out of the spacecraft that they can. And it’s already returning some first-rate science at a relatively low production cost. This is all knowledge that will help us as a civilization live with and understand our often tempestuous star.