[/caption]

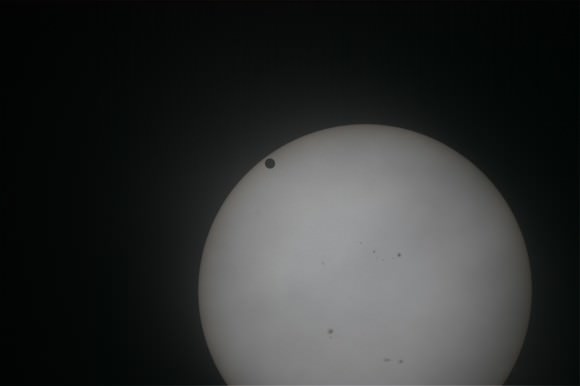

Despite a horrendous weather forecast, the clouds parted – at least partially – just in the nick of time for a massive crowd of astronomy and space enthusiasts gathered at Princeton University to see for themselves the dramatic start of the Transit of Venus shortly after 6 p.m. EDT as it arrived at and crossed the limb of the Sun.

And what a glorious view it was for the well over 500 kids, teenagers and adults who descended on the campus of Princeton University in Princeton, New Jersey for a viewing event jointly organized by the Astrophysics Dept and the Amateur Astronomers Association of Princeton (AAAP), the local astronomy club to which I belong.

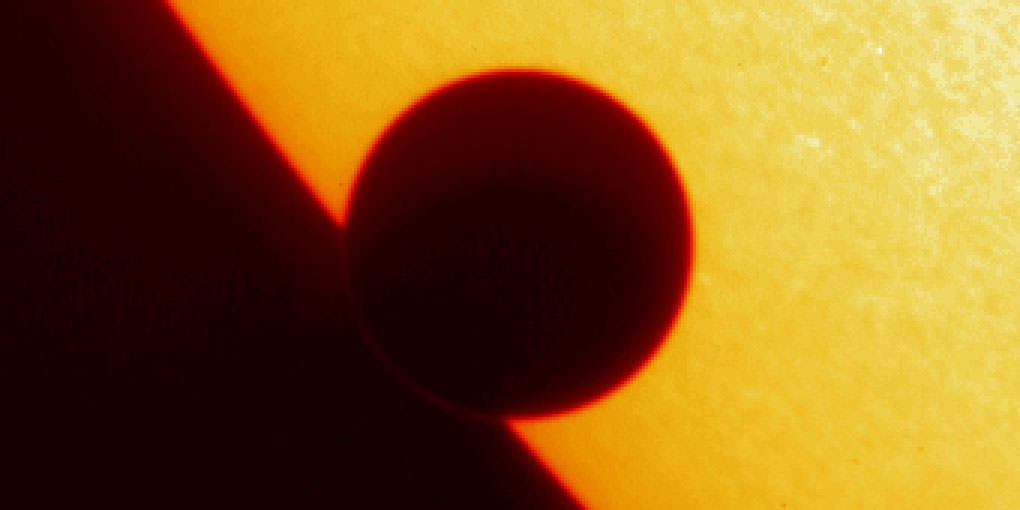

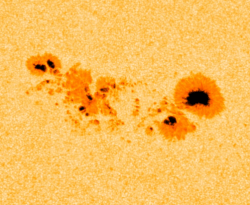

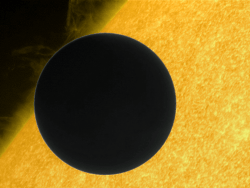

See Transit of Venus astrophotos snapped from Princeton, above and below by Astrophotographer and Prof. Bob Vanderbei of Princeton U and a AAAP club member.

This photo was taken with a Questar telescope at 6:26 p.m. on June 5, 2012 - it’s a stack of eight - 2 second images. Stacking essentially eliminates the clouds. Hundreds attended the Transit of Venus observing event organized jointly by Princeton University Astrophysics Dept and telescopes provided by the Amateur Astronomers Association of Princeton (AAAP), local astronomy club. Credit: Robert Vanderbei

It was gratifying to see so many children and whole families come out at dinner time to witness this ultra rare celestial event with their own eyes – almost certainly a last-in-a-lifetime experience that won’t occur again for another 105 years until 2117. The crowd gathered on the roof of Princeton’s Engineering Dept. parking deck – see photos

Credit: Ken Kremer

For the next two and a half hours until sunset at around 8:30 p.m. EDT, we enjoyed spectacular glimpses as Venus slowly and methodically moved across the northern face of the sun as the racing clouds came and went on numerous occasions, delighting everyone up to the very end when Venus was a bit more than a third of the way through the solar transit.

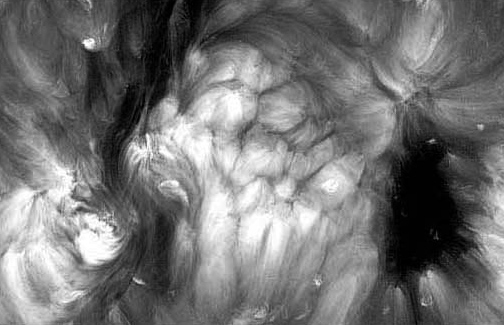

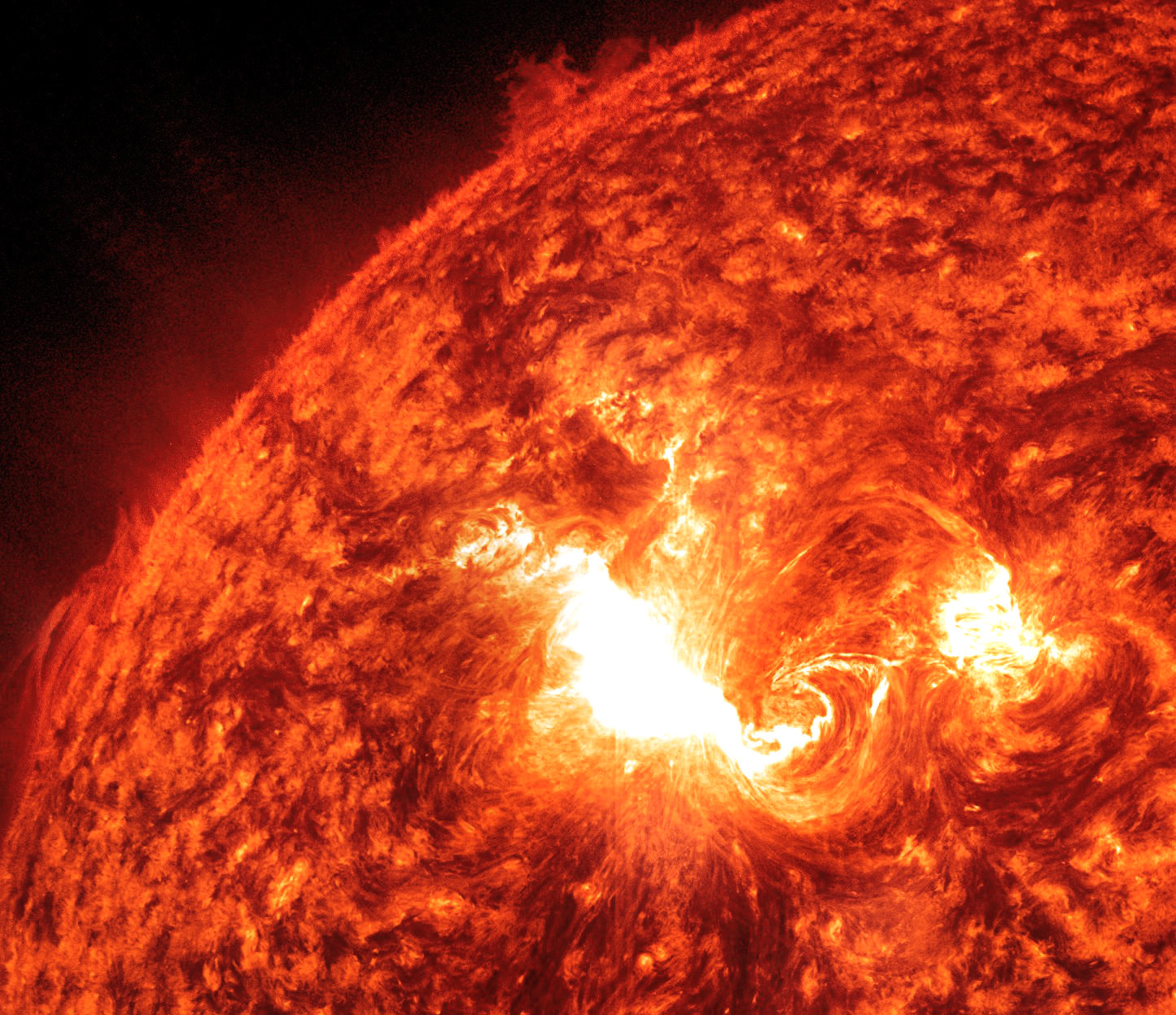

Indeed the flittering clouds passing by in front of Venus and the Sun’s active disk made for an especially eerie, otherworldly and constantly changing scene for all who observed through about a dozen AAAP provided telescopes properly outfitted with special solar filters for safely viewing the sun.

As part of this public outreach program, NASA also sent me special solar glasses to hand out as a safe and alternative way to directly view the sun during all solar eclipses and transits through your very own eyes – but not optical aids such as cameras or telescopes.

This photo was taken with a Questar telescope at 6:26 p.m. on June 5, 2012 - it’s a stack of eight - 2 second images. Credit: Robert Vanderbei

Altogether the Transit lasted 6 hours and 40 minutes for those in the prime viewing locations such as Hawaii – from where NASA was streaming a live Transit of Venus webcast.

You should NEVER look directly at the sun through any telescopes or binoculars not equipped with special eye protection – because that can result in severe eye injury or permanent blindness!

We in Princeton were quite lucky to observe anything because other astro friends and fans in nearby areas such as Philadelphia, PA and Brooklyn, NY reported seeing absolutely nothing for this last-in-a-lifetime celestial event.

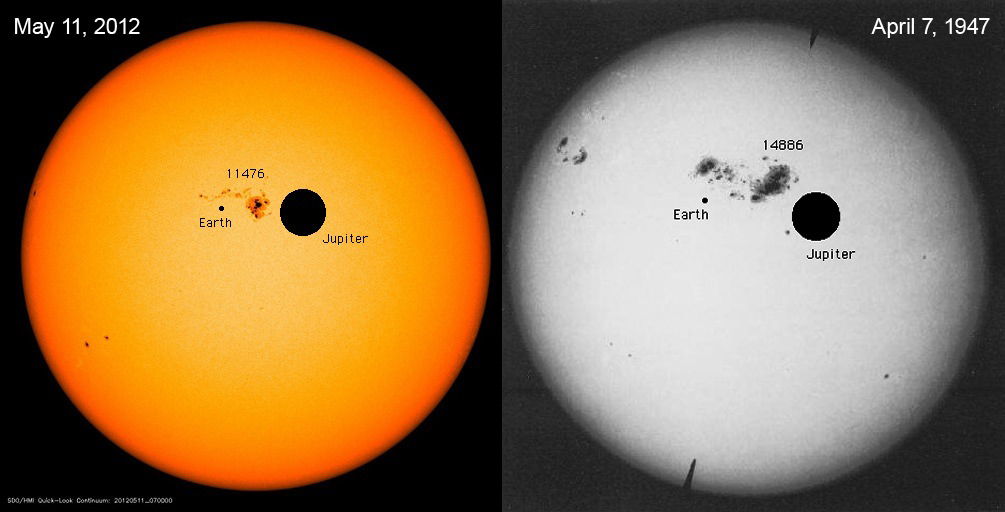

Princeton’s Astrophysics Department organized a series of lectures prior to the observing sessions about the Transit of Venus and how NASA’s Kepler Space Telescope currently uses the transit method to detect and discover well over a thousand exoplanet and planet candidates – a few of which are the size of Earth and even as small as Mars, the Red Planet.

NASA’s Curiosity rover is currently speeding towards Mars for an August 6 landing in search of signs of life. Astronomers goal with Kepler’s transit detection method is to search for Earth-sized planets in the habitable zone that could potentially harbor life !

So, NASA and astronomers worldwide are using the Transit of Venus in a scientifically valuable way – beyond mere enjoyment – to help refine their planet hunting techniques.

Historically, scientists used the Transit of Venus over the past few centuries to help determine the size of our Solar System.

See more event photos from the local daily – The Trenton Times – here

And those who stayed late after sunset – and while the Transit of Venus was still visibly ongoing elsewhere – were treated to an extra astronomical bonus – at 10:07 p.m. EDT the International Space Station (ISS) coincidentally flew overhead and was visible between more break in the clouds.

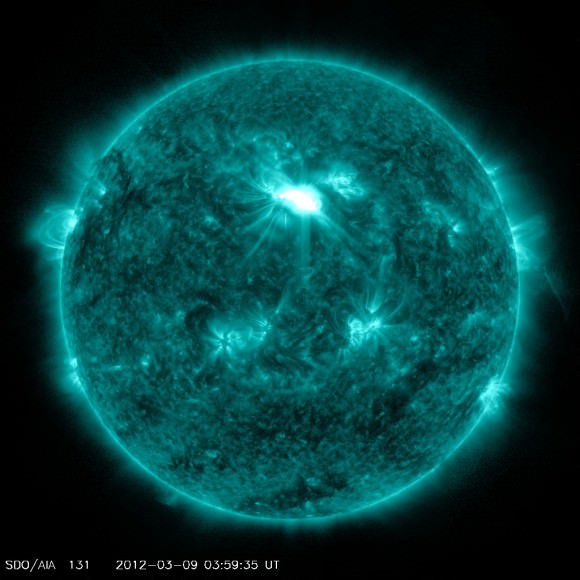

Of course clouds are no issue if you’re watching the Transit of Venus from the ISS or the Hinode spacecraft. See this Hinode Transit image published on APOD on June 9 and enhanced by Marco Di Lorenzo.

This week, local NY & NJ residents also had another extra special space treat – the chance to see another last-in-a-lifetime celestial event: The Transit of Space Shuttle Enterprise across the Manhattan Skyline on a seagoing voyage to her permanent new home at the Intrepid Sea, Air and Space Museum.