Star Trek’s Data must be smiling.

One of his kind has finally made it to the High Frontier. The voyages of Robo Trek have begun !

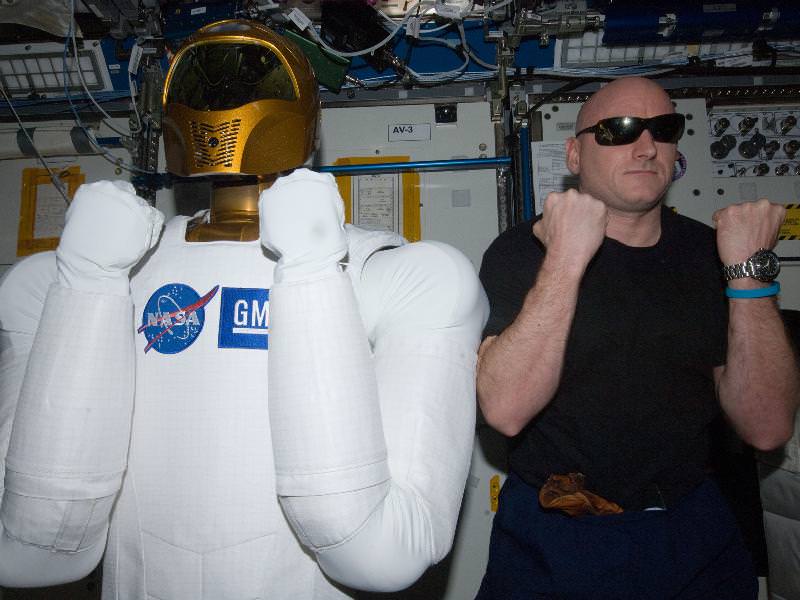

Robonaut 2, or R2, was finally unleashed from his foam lined packing crate by ISS crewmembers Cady Coleman and Paolo Nespoli on March 15 and attached to a pedestal located inside its new home in the Destiny research module. R2 joins the crew of six human residents as an official member of the ISS crew. See the video above and photos below.

[/caption]

The fancy shipping crate goes by the acronym SLEEPR, which stands for Structural Launch Enclosure to Effectively Protect Robonaut. R2 had been packed inside since last summer.

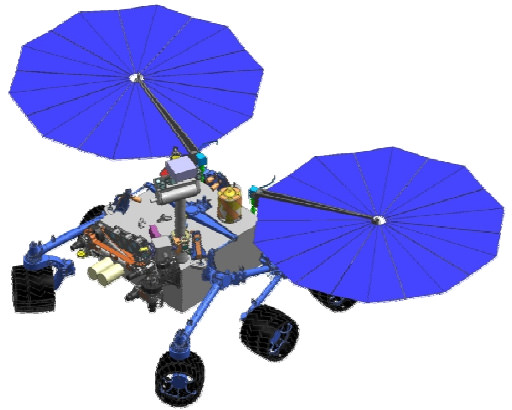

Robonaut 2 is the first dexterous humanoid robot in space and was delivered to the International Space Station by Space Shuttle Discovery on STS-133.

”Robonaut is now onboard as the newest member of our crew. We are happy to have him onboard. It’s a real good opportunity to help understand the interface of humans and robotics here in space.” said Coleman. “We want to see what Robonaut can do. Congratulations to the team of engineers [at NASA Johnson Space center] who got him ready to fly.”

Discovery blasted off for her historic final mission on Feb. 24 and made history to the end by carrying the first joint Human-Robot crew to space.

The all veteran human crew of Discovery was led by Shuttle Commander Steve Lindsey. R2 and SLEEPR were loaded aboard the “Leonardo” storage and logistics module tucked inside the cargo bay of Discovery. Leonardo was berthed at the ISS on March 1 as a new and permanent addition to the pressurized habitable volume of the massive orbiting outpost.

The all veteran human crew of Discovery was led by Shuttle Commander Steve Lindsey. R2 and SLEEPR were loaded aboard the “Leonardo” storage and logistics module tucked inside the cargo bay of Discovery. Leonardo was berthed at the ISS on March 1 as a new and permanent addition to the pressurized habitable volume of the massive orbiting outpost.

“It feels great to be out of my SLEEPR, even if I can’t stretch out just yet. I can’t wait until I get to start doing some work!” tweeted R2.

The 300-pound R2 was jointly developed in a partnership between NASA and GM at a cost of about $2.5 million. It consists of a head and a torso with two arms and two hands. It was designed with exceptionally dexterous hands and can use the same tools as humans.

R2 will function as an astronaut’s assistant that can work shoulder to shoulder alongside humans and conduct real work, ranging from science experiments to maintenance chores. After further upgrades to accomplish tasks of growing complexity, R2 may one day venture outside the ISS to help spacewalking astronauts.

“It’s a dream come true to fly the robot to the ISS,” said Ron Diftler in an interview at the Kennedy Space Center. Diftler is the R2 project manager at NASA’s Johnson Space Center.

President Obama called the joint Discovery-ISS crew during the STS-133 mission and said he was eager to see R2 inside the ISS and urged the crew to unpack R2 as soon as possible.

“I understand you guys have a new crew member, this R2 robot,” Obama said. “I don’t know whether you guys are putting R2 to work, but he’s getting a lot of attention. That helps inspire some young people when it comes to science and technology.”

Commander Lindsey replied that R2 was still packed in the shipping crate – SLEEPR – and then joked that, “every once in a while we hear some scratching sounds from inside, maybe, you know, ‘let me out, let me out,’ we’re not sure.”

Robonaut 2 is free at last to meet his destiny in space and Voyage to the Stars.

“I don’t have a window in front of me, but maybe the crew will let me look out of the Cupola sometime,” R2 tweeted from the ISS.

Read my earlier Robonaut/STS-133 stories here, here, here and here.

I’m in space, says Robonaut 2 from inside the Destiny module at the ISS. Credit: NASA

Robonaut 2, the dexterous humanoid astronaut helper, is pictured in the Destiny laboratory of the International Space Station.

Robonaut R2A waving goodbye as Robonaut R2B launches into space aboard STS-133 from the Kernnedy Space Center. R2 is the first humanoid robot in space. Credit: Joe Bibby

First joint Human – Robot crew. Credit: Ken Kremer

Robonaut 2 and the NASA/GM team of scientists and engineers watched the launch of Space Shuttle Discovery and the first joint Human-Robot crew on the STS-133 mission on Feb. 24, 2011 from the Kennedy Space Center. Credit: Ken Kremer