[/caption]

No, it’s not the Universe Puzzle No. 3; rather, it’s an intriguing result from recent work into the strange shapes and composition of small asteroids.

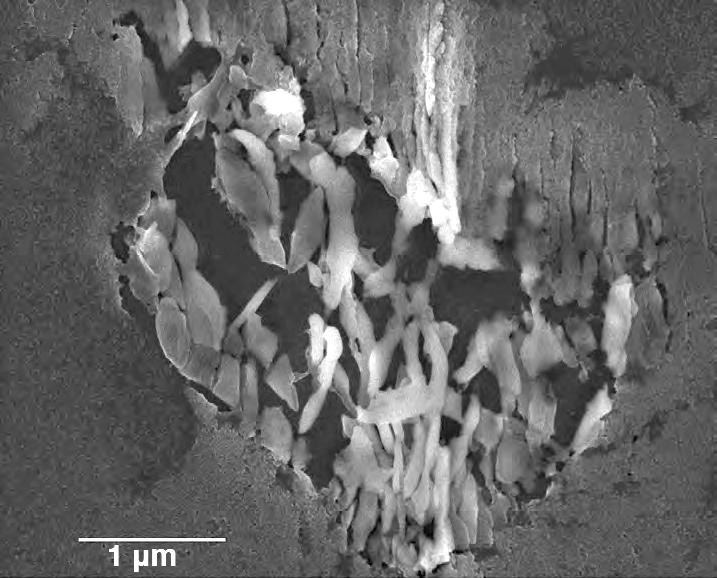

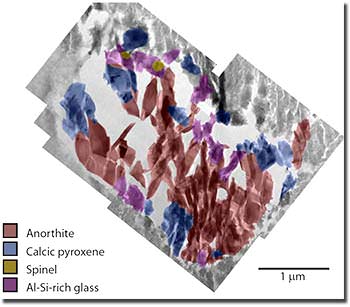

Images sent back from space missions suggest that smaller asteroids are not pristine chunks of rock, but are instead covered in rubble that ranges in size from meter-sized boulders to flour-like dust. Indeed some asteroids appear to be up to 50% empty space, suggesting that they could be collections of rubble with no solid core.

But how do these asteroids form and evolve? And if we ever have to deflect one, to avoid the fate of the dinosaurs, how to do so without breaking it up, and making the danger far greater?

Johannes Diderik van der Waals (1837-1923), with a little help from Daniel Scheeres, Michael Swift, and colleagues, to the rescue.

Asteroids tend to spin rapidly on their axes – and gravity at the surface of smaller bodies can be one thousandth or even one millionth of that on Earth. As a result scientists are left wondering how the rubble clings on to the surface. “The few images that we have of asteroid surfaces are a challenge to understand using traditional geophysics,” University of Colorado’s Scheeres explained.

To get to the bottom of this mystery, the team – Daniel Scheeres, colleagues at the University of Colorado, and Michael Swift at the University of Nottingham – made a thorough study of the relevant forces involved in binding rubble to an asteroid. The formation of small bodies in space involves gravity and cohesion – the latter being the attraction between molecules at the surface of materials. While gravity is well understood, the nature of the cohesive forces at work in the rubble and their relative strengths is much less well known.

The team assumed that the cohesive forces between grains are similar to that found in “cohesive powders” – which include bread flour – because such powders resemble what has been seen on asteroid surfaces. To gauge the significance of these forces, the team considered their strength relative to the gravitational forces present on a small asteroid where gravity at the surface is about one millionth that on Earth. The team found that gravity is an ineffective binding force for rocks observed on smaller asteroids. Electrostatic attraction was also negligible, other than where a portion of the asteroid this is illuminated by the Sun comes into contact with a dark portion.

Fast backward to the mid-19th century, a time when the existence of molecules was controversial, and inter-molecular forces pure science fiction (except, of course, that there was no such thing then). Van der Waals’ doctoral thesis provided a powerful explanation for the transition between gaseous and liquid phases, in terms of weak forces between the constituent molecules, which he assumed have a finite size (more than half a century was to pass before these forces were understood, quantitatively, in terms of quantum mechanics and atomic theory).

Van der Waals forces – weak electrostatic attractions between adjacent atoms or molecules that arise from fluctuations in the positions of their electrons – seem to do the trick for particles that are less than about one meter in size. The size of the van der Waals force is proportional to the contact surface area of a particle – unlike gravity, which is proportional to the mass (and therefore volume) of the particle. As a result, the relative strength of van der Waals compared with gravity increases as the particle gets smaller.

This could explain, for example, recent observations by Scheeres and colleagues that small asteroids are covered in fine dust – material that some scientists thought would be driven away by solar radiation. The research can also have implications on how asteroids respond to the “YORP effect” – the increase of the angular velocity of small asteroids by the absorption of solar radiation. As the bodies spin faster, this recent work suggests that they would expel larger rocks while retaining smaller ones. If such an asteroid were a collection of rubble, the result could be an aggregate of smaller particles held together by van der Waals forces.

Asteroid expert Keith Holsapple of the University of Washington is impressed that not only has Scheeres’ team estimated the forces in play on an asteroid, it has also looked at how these vary with asteroid and particle size. “This is a very important paper that addresses a key issue in the mechanics of the small bodies of the solar system and particle mechanics at low gravity,” he said.

Scheeres noted that testing this theory requires a space mission to determine the mechanical and strength properties of an asteroid’s surface. “We are developing such a proposal now,” he said.

Source: Physics World. “Scaling forces to asteroid surfaces: The role of cohesion” is a preprint by Scheeres, et al. (arXiv:1002.2478), submitted for publication in Icarus.