[/caption]

It’s more than a billion kilometers (759 million miles) away, but the more astronomers learn about Titan, the more it looks like Earth.

That’s the theme of two talks happening this week at the International Astronomical Union meeting in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Two NASA researchers, Rosaly Lopes and Robert M. Nelson of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, are reporting that weather and geology have very similar actions on Earth and Titan — even though Saturn’s moon is, on average, 100 degrees C (212 degrees F) colder than Antarctica (and certainly much more frigid than either California or Brazil; lucky astronomers).

The researchers are also reporting a tantalizing clue in the search for life: Titan hosts chemistry much like pre-biotic conditions on Earth.

Wind, rain, volcanoes, tectonics and other Earth-like processes all sculpt features on Titan’s complex and varied surface — except, according to additional research being presented at the meeting, scientists think the “cryovolcanoes” on Titan eject cold slurries of water-ice and ammonia instead of scorching hot magma.

“It is really surprising how closely Titan’s surface resembles Earth’s,” Lopes said. “In fact, Titan looks more like the Earth than any other body in the Solar System, despite the huge differences in temperature and other environmental conditions.”

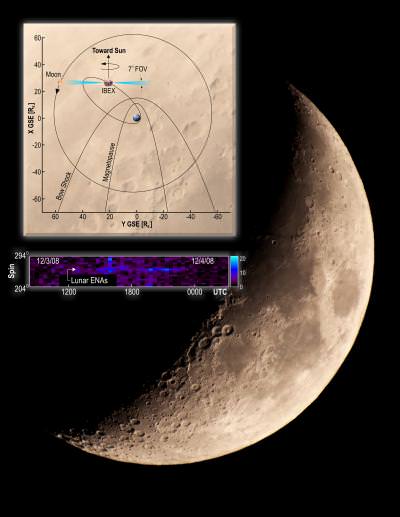

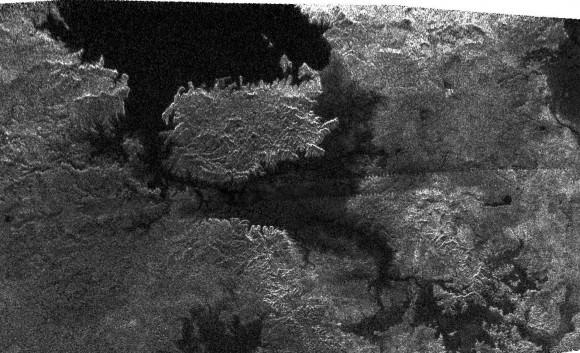

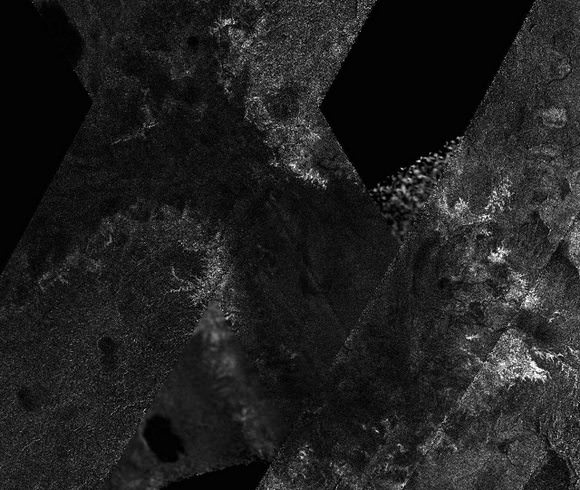

The joint NASA/ESA/ASI Cassini-Huygens mission has revealed details of Titan’s geologically young surface, showing few impact craters, and featuring mountain chains, dunes and even “lakes.” The RADAR instrument on the Cassini orbiter has now allowed scientists to image a third of Titan’s surface using radar beams that pierce the giant moon’s thick, smoggy atmosphere. There is still much terrain to cover, as the aptly named Titan is one of the biggest moons in the Solar System, larger than the planet Mercury and approaching Mars in size.

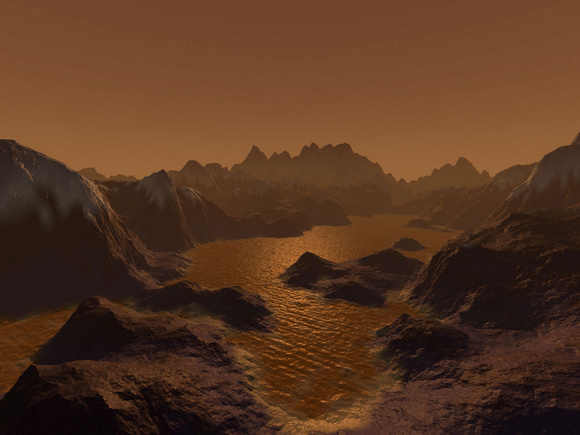

Titan has long fascinated astronomers as the only moon known to possess a thick atmosphere, and as the only celestial body other than Earth to have stable pools of liquid on its surface. The many lakes that pepper the northern polar latitudes, with a scattering appearing in the south as well, are thought to be filled with liquid hydrocarbons, such as methane and ethane.

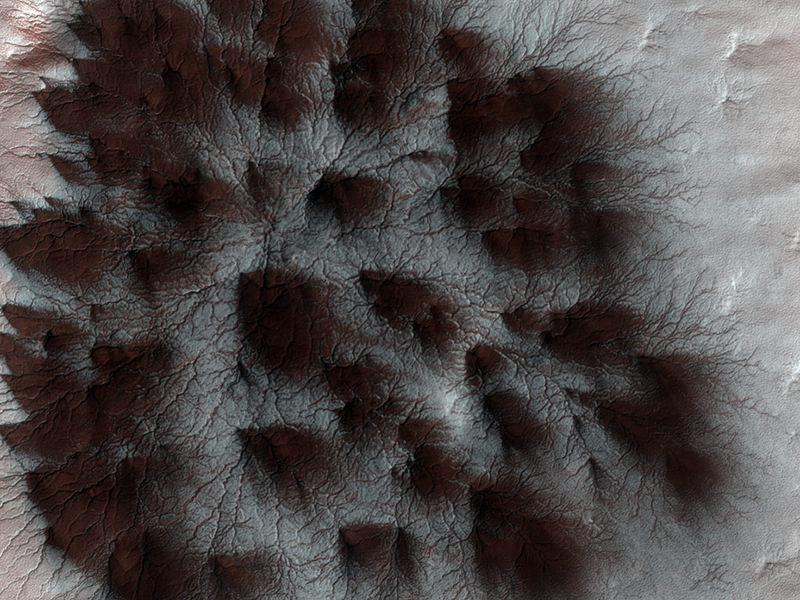

On Titan, methane takes water’s place in the hydrological cycle of evaporation and precipitation (rain or snow) and can appear as a gas, a liquid and a solid. Methane rain cuts channels and forms lakes on the surface and causes erosion, helping to erase the meteorite impact craters that pockmark most other rocky worlds, such as our own Moon and the planet Mercury.

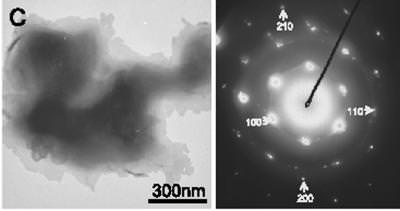

Another Cassini instrument called the Visual and Infrared Mapping Spectrometer (VIMS) had previously detected an area, called Hotei Regio, with a varying infrared signature, suggesting the temporary presence of ammonia frosts that subsequently dissipated or were covered over. Although the ammonia does not stay exposed for long, models show that it exists in Titan’s interior, indicating that a process is at work delivering ammonia to the surface. RADAR imaging has indeed found structures that resemble terrestrial volcanoes near the site of suspected ammonia deposition.

Nelson said new infrared images of the region, also presented at the IAU, “provide further evidence suggesting that cryovolcanism has deposited ammonia onto Titan’s surface. It has not escaped our attention that ammonia, in association with methane and nitrogen, the principal species of Titan’s atmosphere, closely replicates the environment at the time that life first emerged on Earth. One exciting question is whether Titan’s chemical processes today support a prebiotic chemistry similar to that under which life evolved on Earth?”

Many Titan researchers hope to observe Titan with Cassini for long enough to follow a change in seasons. Lopes thinks that the hydrocarbons there likely evaporated because this hemisphere is experiencing summer. When the seasons change in several years and summer returns to the northern latitudes, the lakes so common there may evaporate and end up pooling in the south.

Lead image caption: Artist’s impression of hydrocarbon pools, icy and rocky terrain on the surface of Saturn’s largest moon Titan. Image credit: Steven Hobbs (Brisbane, Queensland, Australia)

Source: International Astronomical Union (IAU)