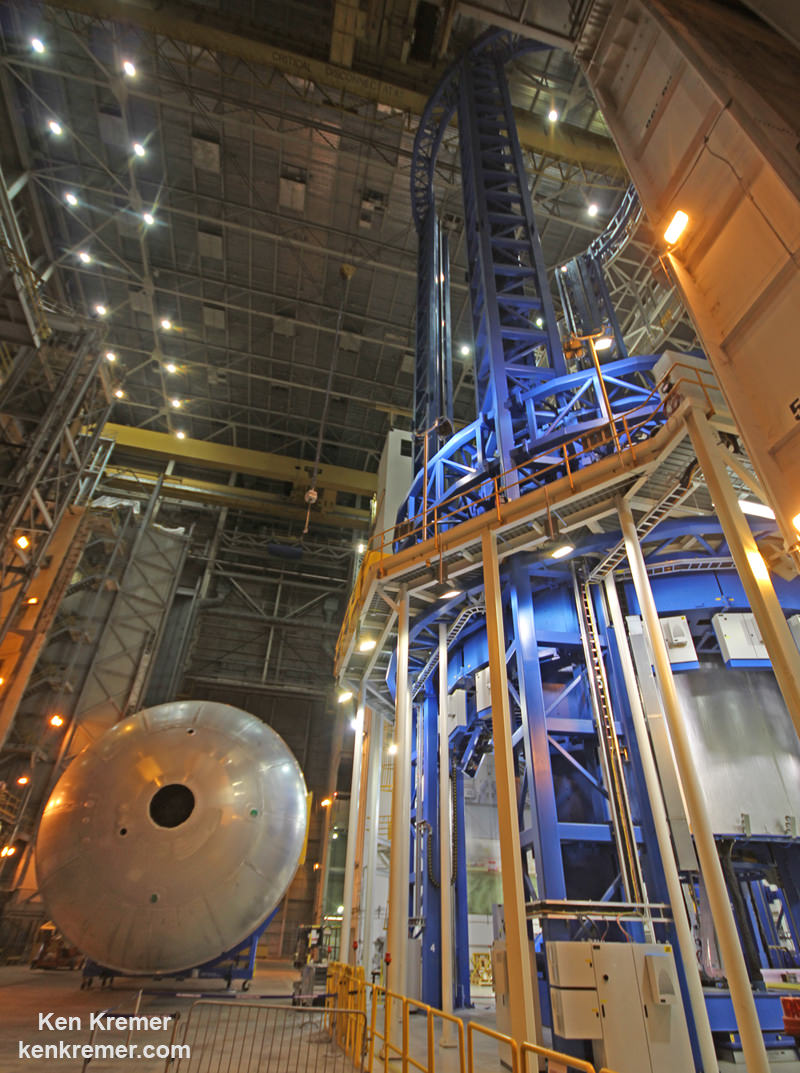

NASA WALLOPS FLIGHT FACILITY, VA – After a two year stand down, an upgraded commercial Antares rocket was rolled out to the NASA Wallops launch pad on Virginia’s eastern shore and raised to its launch position today in anticipation of a spectacular Sunday night liftoff, Oct. 16, to the International Space Station (ISS) on a critical resupply mission for NASA.

Blastoff of the re-engined Orbital ATK Antares rocket is slated for 8:03 p.m. EDT on Oct. 16 from the Mid-Atlantic Regional Spaceport pad 0A at NASA’s Wallops Flight Facility on Virginia’s picturesque Eastern shore.

The two year lull in Antares launches followed the rockets immediate grounding after its catastrophic failure just moments after liftoff on Oct. 28, 2014 that doomed the Orb-3 resupply mission to the space station – as witnessed by this author.

Officials had to postpone this commercial resupply mission – dubbed OA-5 – from mid-week due to Cat 3 Hurricane Nicole which slammed into Bermuda yesterday, Oct. 13, packing winds of about 125 mph, and is home to a critical NASA launch tracking station.

After the storm passed, engineers found the tracking station only suffered minor damage – so the GO was given to proceed with preparation for Sunday’s nighttime launch.

“Repairs to the station have been made and the team is currently readying to support the launch,” according to NASA officials.

Engineers are still testing the station to ensure its readiness.

“The Bermuda site provides tracking, telemetry and flight terminations support for Antares launches from NASA’s Wallops Flight Facility on Virginia’s Eastern Shore. Final testing is scheduled to be conducted the morning of Oct. 15 prior to the launch readiness review later that day.”

If all goes well Antares is sure to provide a dazzling nighttime skyshow from NASA’s Virginia launch base Sunday night – and potentially offering a thrilling spectacle to millions of US East Coast spectators.

The launch window last five minutes and the weather outlook is currently favorable.

The launch will air live on NASA TV and the agency’s website beginning at 7 p.m. EDT Oct 16.

The 133-foot-tall (40-meter) Antares was rolled out to pad 0A on Thursday, Oct. 13 – three days prior to the anticipated launch date – and raised to the vertical launch position this afternoon.

The two stage Antares will carry the Orbital OA-5 Cygnus cargo freighter to orbit on a flight bound for the ISS and its multinational crew of astronauts and cosmonauts.

The launch marks the first nighttime liftoff of the Antares – and it could be visible up and down the eastern seaboard if weather and atmospheric conditions cooperate to provide a spectacular viewing opportunity to the most populated region in North America.

The 14 story tall commercial Antares rocket also will launch for the first time in the upgraded 230 configuration – powered by new Russian-built first stage engines.

Orbital ATK’s Antares commercial rocket had to be overhauled with the completely new RD-181 first stage engines – fueled by LOX/kerosene – following the destruction of the Antares rocket and Cygnus supply ship two years ago.

The RD-181 replaces the previously used AJ26 engines which failed moments after liftoff during the last launch on Oct. 28, 2014 resulting in a catastrophic loss of the rocket and Cygnus cargo freighter.

The launch mishap was traced to a failure in the AJ26 first stage engine turbopump and caused Antares launches to immediately grind to a halt.

For the OA-5 mission, the Cygnus advanced maneuvering spacecraft will be loaded with approximately 2,400 kg (5,290 lbs.) of supplies and science experiments for the International Space Station (ISS).

“Cygnus is loaded with the Saffire II payload and a nanoracks cubesat deployer,” Frank DeMauro, Orbital ATK Cygnus program manager, told Universe Today in a interview.

Among the science payloads aboard the Cygnus OA-5 mission is the Saffire II payload experiment to study combustion behavior in microgravity. Data from this experiment will be downloaded via telemetry. In addition, a NanoRack deployer will release Spire Cubesats used for weather forecasting. These secondary payload operations will be conducted after Cygnus departs the space station.

Other experiments include a study on the effect of lighting on sleep and daily rhythms, collection of health-related data, and a new way to measure neutrons.

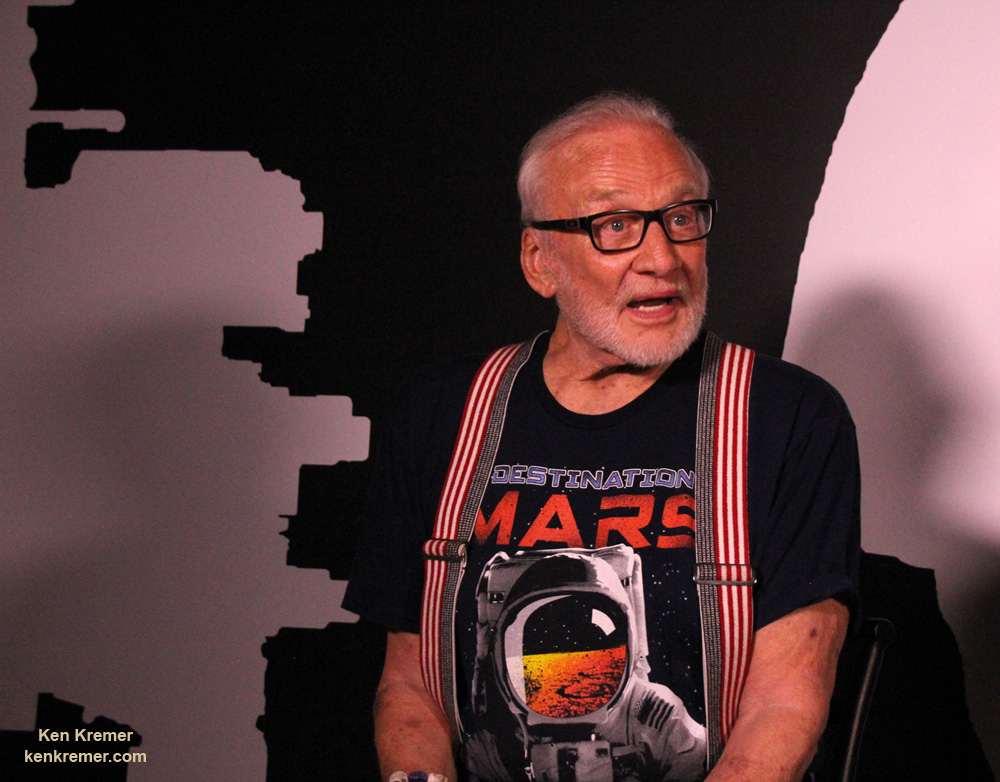

Watch for Ken’s continuing Antares/Cygnus mission and launch reporting. He will be reporting from on site at NASA’s Wallops Flight Facility, VA during the launch campaign.

The Cygnus spacecraft for the OA-5 mission is named the S.S. Alan G. Poindexter in honor of former astronaut and Naval Aviator Captain Alan Poindexter.

Under the Commercial Resupply Services (CRS) contract with NASA, Orbital ATK will deliver approximately 28,700 kilograms of cargo to the space station. OA-5 is the sixth of these missions.

Stay tuned here for Ken’s continuing Earth and Planetary science and human spaceflight news.

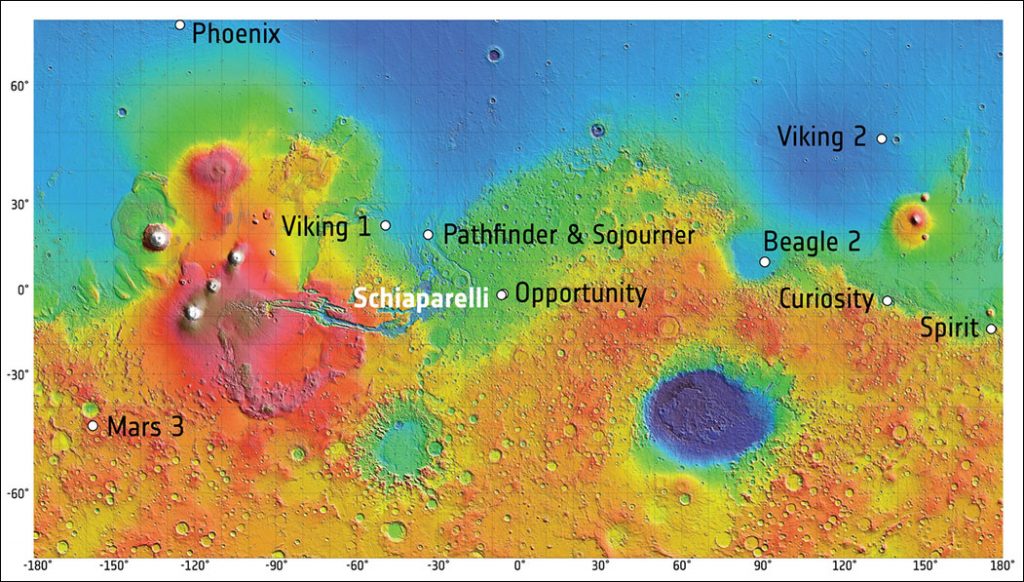

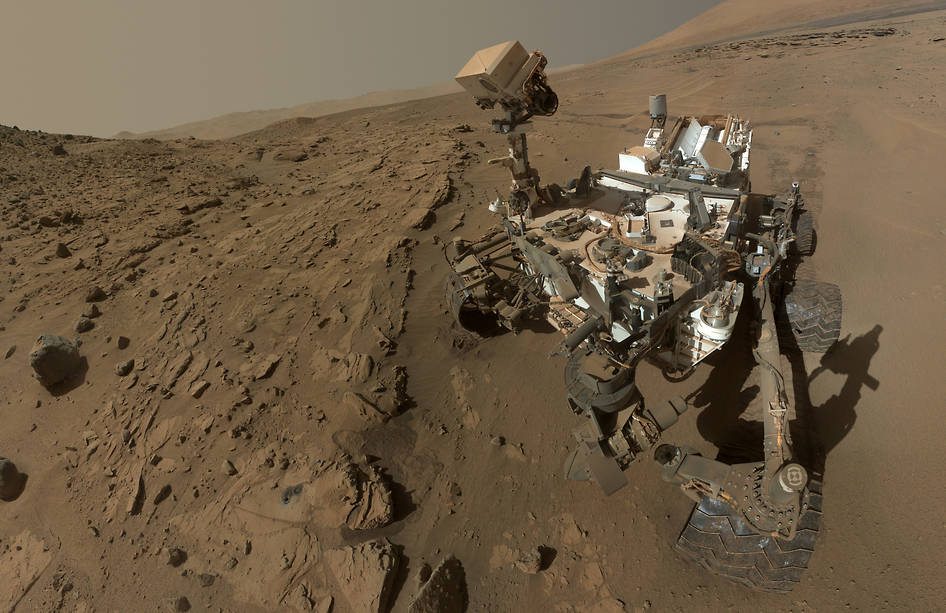

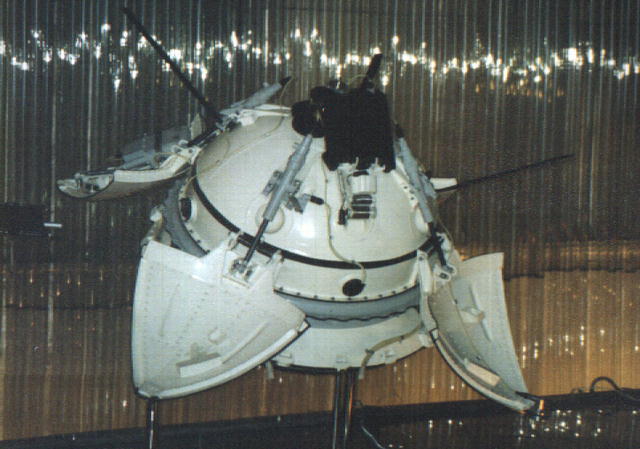

![The Viking 2 lander captured this image of itself on the Martian surface. By NASA - NASA website; description,[1] high resolution image.[2], Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=17624](https://www.universetoday.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/608px-Viking2lander1.jpg)