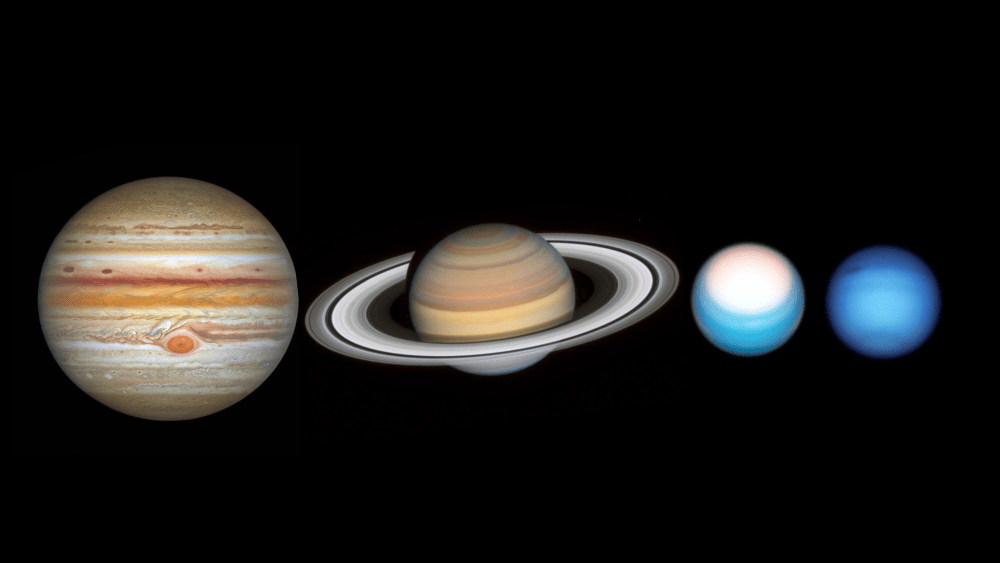

To date, a total of 4,884 extrasolar planets have been confirmed in 3,659 systems, with another 8,414 additional candidates awaiting confirmation. In the course of studying these new worlds, astronomers have noted something very interesting about the “rocky” planets. Since Earth is rocky and the only known planet where life can exist, astronomers are naturally curious about this particular type of planet. Interestingly, most of the rocky planets discovered so far have been many times the size and mass of Earth.

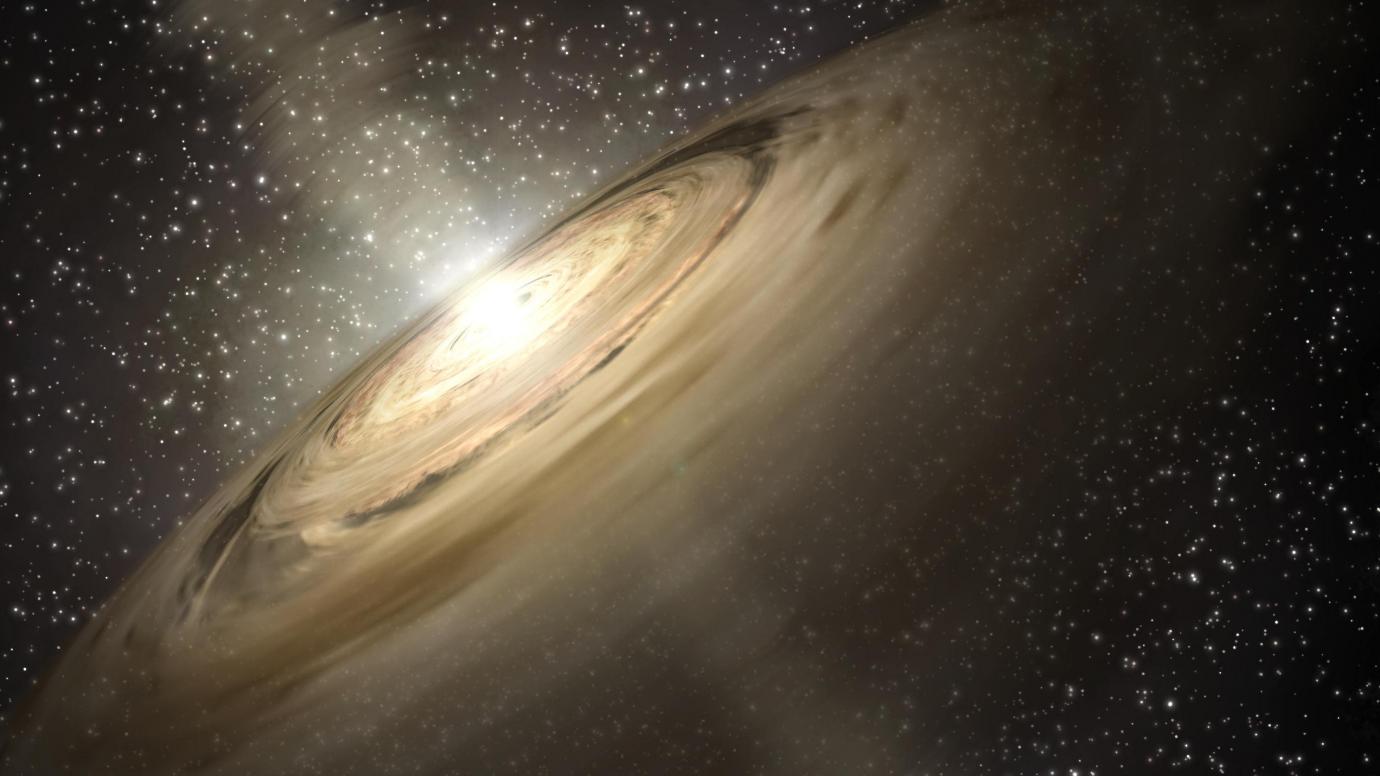

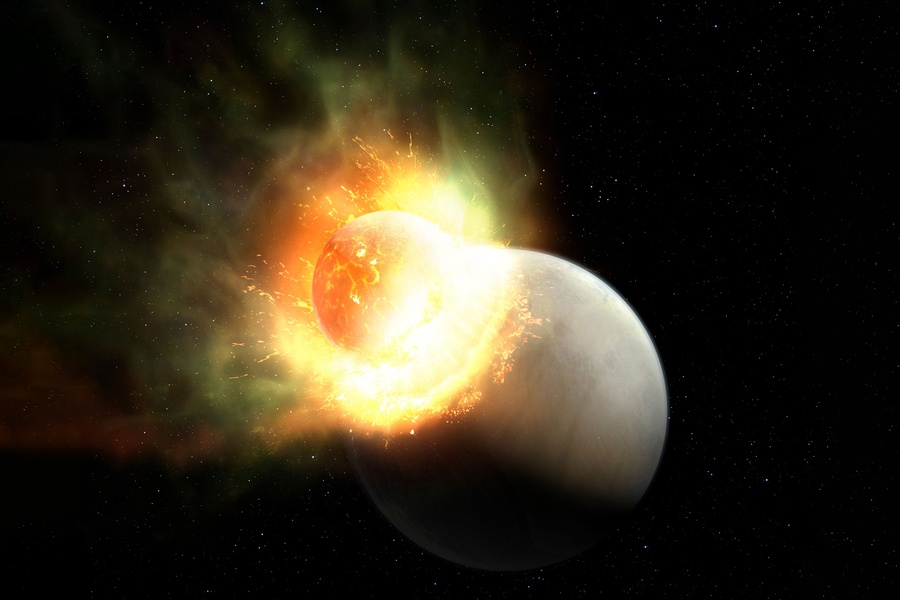

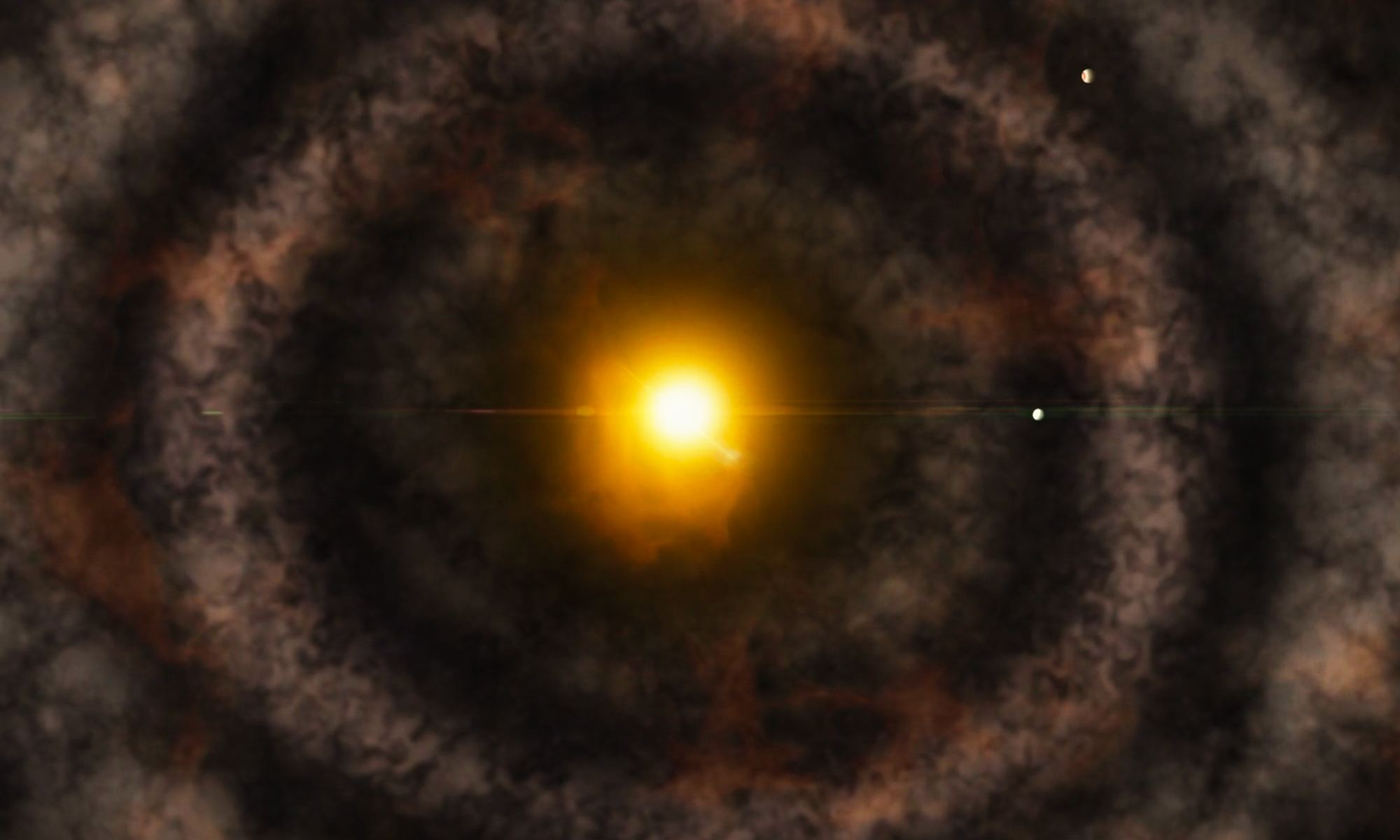

Of the 1,702 rocky planets confirmed to date, the majority (1,516) have been “Super-Earths,” while only 186 have been similar in size and mass to Earth. This raises the question: is Earth an outlier, or do we not have enough data yet to determine how common “Earth-like” planets are. According to new research by an international team led by Rice University, it may all have to do with protoplanetary rings of dust and gas in an early solar system.

Continue reading “Rings in the Early Solar System Kept our Planet From Becoming a Super-Earth”